| Wee Fit: Prefab Construction for Small (and Not so Small) Spaces

by Tracy Ostroff

Contributing Editor

How do you . . . practice prefab?

Summary: It has been about six years since Alchemy Architects constructed its first weeHouse, an ultrapragmatic architectural solution for a client on a $45,000 budget. (Yes, you read that right.) The sleek, contemporary home in Pepin, Wisc., turned out to be a harbinger of a customized prefab practice model that the architects have refined to a tee (or is that a wee?).

The client, Stephanie Arado, a violinist with the Minnesota Orchestra, came to Alchemy Architects, founded by Geoffrey Warner, AIA, and asked what they could do to construct a home for her and her son with that limited budget. Warner and his colleagues, who—as artisans in their woodshop warehouse—were used to fashioning solutions from everyday items, decided to see if they could meet the challenge. Warner recalls: “Instead of laughing, we said, ‘well, what can we do?’” The design team vetted solutions until the idea of a shipping container stuck. The client, Stephanie Arado, a violinist with the Minnesota Orchestra, came to Alchemy Architects, founded by Geoffrey Warner, AIA, and asked what they could do to construct a home for her and her son with that limited budget. Warner and his colleagues, who—as artisans in their woodshop warehouse—were used to fashioning solutions from everyday items, decided to see if they could meet the challenge. Warner recalls: “Instead of laughing, we said, ‘well, what can we do?’” The design team vetted solutions until the idea of a shipping container stuck.

The architects, with their design-build and artisan backgrounds, had to work out many details, such as how you insulate such a structure in Minnesota and how you handle off-site construction. For each question they found an answer. They built the home in their warehouse and in donated bays at an Anderson warehouse site. They shipped it to the site and dropped it by crane onto piers.

Alchemy came in on budget “in the holistic sense,” Warner says, but fiscally speaking they broke the spending limit by about $13,000. But, Warner says, the process was also a study in optimism through asking: “What can you do with the tools you have?” The answer spawned a new business and is helping to bring prefab houses into mainstream consciousness. Alchemy came in on budget “in the holistic sense,” Warner says, but fiscally speaking they broke the spending limit by about $13,000. But, Warner says, the process was also a study in optimism through asking: “What can you do with the tools you have?” The answer spawned a new business and is helping to bring prefab houses into mainstream consciousness.

More and more wees

Since Alchemy LLC launched the weeHouse design in 2003, they have

built more than 16 weeHouses across the U.S. and Canada and are

working with clients on more than 18 others in various design-build

stages. Their work has been the subject of several major art shows,

including an installation at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis.

Clients use weeHouses as homes, offices, penthouses, and studios.

They range from 341-square-foot studios to four-plus module dwellings

over 2,000 square feet. All are prefabricated and then set on site.

They also have plans for a weeHouse Boat and weeHouse communities

or collections of weeHouses. “You never know,” Warner

conjectures.

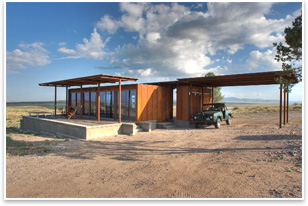

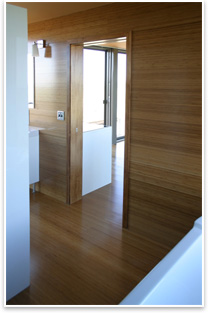

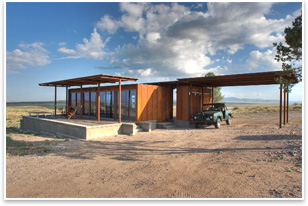

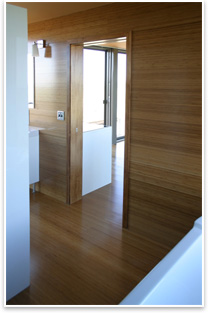

Although weeHouses can be customized to a certain extent, they do

come, literally, with the kitchen sink, and all other major appliances

and cabinetry. The weeHouse standard flooring is a 1x4 tongue-and-groove

bamboo (light or dark finish available), and all interior walls are

white gypsum board. They integrate a curtain track into the perimeter

ceiling as a standard feature, which allows for privacy curtains

or wall texture panels. Standard weeHouse bathrooms have tile floors

and showers. Each weeHouse also includes floor-to-ceiling glass doors,

container siding (cement fiberboard with vertical battens), EPDM

cold roof, primed gypboard ceilings and walls, electrical and plumbing

systems, fixtures, bathroom tile, and cabinets. Although weeHouses can be customized to a certain extent, they do

come, literally, with the kitchen sink, and all other major appliances

and cabinetry. The weeHouse standard flooring is a 1x4 tongue-and-groove

bamboo (light or dark finish available), and all interior walls are

white gypsum board. They integrate a curtain track into the perimeter

ceiling as a standard feature, which allows for privacy curtains

or wall texture panels. Standard weeHouse bathrooms have tile floors

and showers. Each weeHouse also includes floor-to-ceiling glass doors,

container siding (cement fiberboard with vertical battens), EPDM

cold roof, primed gypboard ceilings and walls, electrical and plumbing

systems, fixtures, bathroom tile, and cabinets.

Alchemy has been promoting its weeHouse ‘”standards” program

since 2007 with a robust animated Web site presence. The sustainably

minded firm does not print its materials. They are also looking forward

to launching a “build-a-wee,” which Warner says will

allow potential clients to play with customizing their designs, like

the way they can customize a MINI on the Web. The basic weeHouse

box is 14 feet wide. Anything larger than that gets complicated to

move on a truck.

The standards represent a focused refinement of Alchemy’s experience in designing, building, and creating the weeHouse. The weeHouse encourages efficiency in the design and planning process and ultimately in the production process. Utilizing 13 floor-plan templates, Alchemy is able to generate construction drawings quickly while integrating cutting-edge options including radiant in-floor heat, various heating/cooling methods, and stylish fixtures. For the factory, these systemized drawings help to procure stock expeditiously, discouraging waste. Overall, modular units minimize waste by maximizing the amount of work done in the factory. Factory production also provides a centralized location for the construction trades and allows them to coordinate their work and reduce vehicular emissions generated from travel to the construction site.

Really sustainable Really sustainable

Alchemy Architects prides itself on its commitment to the sustainability of its weeHouses. They work with the factories to construct homes that meet EnergyStar®, Build It Green, and LEED® standards. Each weeHouse is tailored to its owners’ needs and receives a “genuine” numbered and custom-named aluminum doorbell plate that certifies its weeHouse authenticity. Prices for the different schemes are listed on the Web site. “Why wouldn’t we have prices on there?” Warner muses. (West Coast standards weeHouse prices range from $79,000 to $245,000, according to the Alchemy Web site, and include design fees.)

Make no wee plans

Warner doesn’t see his firm’s work as a threat to architecture “with a Capital A.” Instead, he sees it as a way to connect with people who never would have considered working with an architect. He also views Alchemy’s foray into prefab construction as an example of the type of experimentation that keeps the profession young and vibrant, which is especially important to encourage in small firms like his. “You take a lot of risks to think about doing work in different ways.” Warner appreciates first-hand that it is hard to think outside the box—or in his case “inside the box”—when the pressures of practice and finances loom large.

Warner, who notes he wasn’t an AIA member until four or five years ago, says he is heartened that the profession is moving toward an understanding that “it’s not only large firms doing important projects that advances the way architecture is produced and perceived.” He sees building information modeling and robotics as the waves of the future, but notes that “we still have to design the thing and value engineer it.” Warner, who notes he wasn’t an AIA member until four or five years ago, says he is heartened that the profession is moving toward an understanding that “it’s not only large firms doing important projects that advances the way architecture is produced and perceived.” He sees building information modeling and robotics as the waves of the future, but notes that “we still have to design the thing and value engineer it.”

“It’s not threatening to the profession. This is a way of doing work that has potential. It’s just one more tool we have to build cheaper, better, and faster. It serves the idea in the end. It’s a win-win.”

|

The client, Stephanie Arado, a violinist with the Minnesota Orchestra, came to Alchemy Architects, founded by Geoffrey Warner, AIA, and asked what they could do to construct a home for her and her son with that limited budget. Warner and his colleagues, who—as artisans in their woodshop warehouse—were used to fashioning solutions from everyday items, decided to see if they could meet the challenge. Warner recalls: “Instead of laughing, we said, ‘well, what can we do?’” The design team vetted solutions until the idea of a shipping container stuck.

The client, Stephanie Arado, a violinist with the Minnesota Orchestra, came to Alchemy Architects, founded by Geoffrey Warner, AIA, and asked what they could do to construct a home for her and her son with that limited budget. Warner and his colleagues, who—as artisans in their woodshop warehouse—were used to fashioning solutions from everyday items, decided to see if they could meet the challenge. Warner recalls: “Instead of laughing, we said, ‘well, what can we do?’” The design team vetted solutions until the idea of a shipping container stuck. Alchemy came in on budget “in the holistic sense,” Warner says, but fiscally speaking they broke the spending limit by about $13,000. But, Warner says, the process was also a study in optimism through asking: “What can you do with the tools you have?” The answer spawned a new business and is helping to bring prefab houses into mainstream consciousness.

Alchemy came in on budget “in the holistic sense,” Warner says, but fiscally speaking they broke the spending limit by about $13,000. But, Warner says, the process was also a study in optimism through asking: “What can you do with the tools you have?” The answer spawned a new business and is helping to bring prefab houses into mainstream consciousness. Although weeHouses can be customized to a certain extent, they do

come, literally, with the kitchen sink, and all other major appliances

and cabinetry. The weeHouse standard flooring is a 1x4 tongue-and-groove

bamboo (light or dark finish available), and all interior walls are

white gypsum board. They integrate a curtain track into the perimeter

ceiling as a standard feature, which allows for privacy curtains

or wall texture panels. Standard weeHouse bathrooms have tile floors

and showers. Each weeHouse also includes floor-to-ceiling glass doors,

container siding (cement fiberboard with vertical battens), EPDM

cold roof, primed gypboard ceilings and walls, electrical and plumbing

systems, fixtures, bathroom tile, and cabinets.

Although weeHouses can be customized to a certain extent, they do

come, literally, with the kitchen sink, and all other major appliances

and cabinetry. The weeHouse standard flooring is a 1x4 tongue-and-groove

bamboo (light or dark finish available), and all interior walls are

white gypsum board. They integrate a curtain track into the perimeter

ceiling as a standard feature, which allows for privacy curtains

or wall texture panels. Standard weeHouse bathrooms have tile floors

and showers. Each weeHouse also includes floor-to-ceiling glass doors,

container siding (cement fiberboard with vertical battens), EPDM

cold roof, primed gypboard ceilings and walls, electrical and plumbing

systems, fixtures, bathroom tile, and cabinets. Really sustainable

Really sustainable Warner, who notes he wasn’t an AIA member until four or five years ago, says he is heartened that the profession is moving toward an understanding that “it’s not only large firms doing important projects that advances the way architecture is produced and perceived.” He sees building information modeling and robotics as the waves of the future, but notes that “we still have to design the thing and value engineer it.”

Warner, who notes he wasn’t an AIA member until four or five years ago, says he is heartened that the profession is moving toward an understanding that “it’s not only large firms doing important projects that advances the way architecture is produced and perceived.” He sees building information modeling and robotics as the waves of the future, but notes that “we still have to design the thing and value engineer it.”