| Irvington

Terrace: A Modern Take on California Mission MVE and Partners’ low-income housing development mixes contemporary urban living with the traditional town square How do you . . . adapt contextually historicist styles through the aesthetic lens of contemporary Modernism to design affordable housing? Summary: Irvington Terrace references California Mission architecture, the work of early Modernist architect Irving Gill, and traditional village-square site organization, and yet it focuses these influences into a contemporarily urban design. As affordable housing, it meets residents halfway with familiar contextual and historicist forms.

MVE’s design acumen isn’t cut from whole cloth here. This balance of new world simplicity and fundamentally established village models in a West Coast context was explored by California proto-Modernist Irving Gill and exerted overt influence on this project, say the project’s designers.

The development’s site was a disused shopping center in a commercial zoning area, and the City of Fremont (which requires that 15 percent of all market-rate development be affordable housing, according to California Construction) and the complex’s nonprofit developers, BRIDGE Housing, wanted Irvington Terrace to add density and walkable livability to the newly mixed-use zoning area. At three stories tall, Irvington Terrace can fit 40 units to an acre.

These front stoops help to obscure the subtle ground-level increase in elevation that is a result of the underground parking garage. By leading the eye directly from the front door down to the street, the stoops make the units appear as though they’re sitting on top of English basement apartments. Ernesto Vasquez, AIA, a vice president and partner at MVE, says he chose to hide the parking structure beneath the units to maintain the neighborhood’s sense of scale.

There is no utilitarian “backside” to Irvington Terrace, which Vasquez says enhances the neighborhood’s security and sense of community by (quoting urbanist and author Jane Jacobs) keeping “eyes on the street.”

In abstract

A native of East Los Angeles, Vasquez says that with affordable housing, all design aspirations must be balanced with the risk of cultural dislocation of the residents, and Irvington Terrace seeks to even these scales. It has a traditional single-unit and community-oriented family scale with references to familiar aesthetic motifs, yet still appropriates a contemporarily urban mixed-use identity. “We need to think in terms of the occupant and the tenant, and the families that are going to live there,” he says. “How do they feel?” |

||

Copyright 2008 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Hope IV Development Brings Sustainability to Low-Income Housing

› Can Affordable Housing Be Sustainable?

› The New Suburban Migration

Visit MVE and Partners’ Web site.

Visit BRIDGE Housing’s Web site.

See what the Communities by Design Knowledge Community is up to.

Do you know SOLOSO?

Read “Putting Design Back in Affordable Housing,” a multimedia report containing case studies and best practices for creating well-designed low-income housing developments.

See what else SOLOSO has to offer for your practice.

From the AIA Bookstore: Living Together: Multi-Family Housing Today, by Michael Crosbie, published by Images Publishing Group, 2007.

Captions:

Photos © Eric Figge.

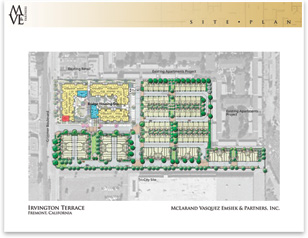

1. Irvington Terrace’s 100 rental units all cluster around two

landscaped courtyards.

2. Trellises and pergolas, similar to traditional

California Mission arcades, unite the complex and complement the earth-toned,

three-story structures.

3. Front stoops enliven the adjacent streetscape.

4. Pergolas offer shade

to residents in the village square-like courtyard.

5. An inward-facing

section contains public meeting spaces for residents.

The low-income housing development of Irvington Terrace in Fremont, Calif., strikes a fine balance between progressive Modernist forms and a traditional village-square-like community. Designed by MVE and Partners, it forms a block-long perimeter of flat-roofed rental apartments, articulated with interlocking rectilinear volumes that define individual units. These fused and richly textured units avoid the monumental austerity of past failed experiments in Modernist affordable housing by providing street wall relief and variety, complete with street-enlivening stoops and porches. These rows of housing surround two town-square courtyards with adjacent public amenities.

The low-income housing development of Irvington Terrace in Fremont, Calif., strikes a fine balance between progressive Modernist forms and a traditional village-square-like community. Designed by MVE and Partners, it forms a block-long perimeter of flat-roofed rental apartments, articulated with interlocking rectilinear volumes that define individual units. These fused and richly textured units avoid the monumental austerity of past failed experiments in Modernist affordable housing by providing street wall relief and variety, complete with street-enlivening stoops and porches. These rows of housing surround two town-square courtyards with adjacent public amenities. Contemporary urbanity and traditional community

Contemporary urbanity and traditional community Wood-framed and plastered in a variety of earth tones, each connected unit has its own entrance to maintain a single-family-unit feel. The development’s offset, interlocking, and set-back rectilinear volumes enhance its close neighborhood feel, hinting at diverse urban uses and functions through the playful intersection of masses, although the project essentially has only a single function. This play of forms creates a terracing effect of sorts, from front protruding volumes that reach down to the streetscape with stoops that provide neighborhood gathering places to set-back rectilinear volumes on top levels that subtly evoke the bell towers of one of the project’s aesthetic touchstones: California Mission architecture.

Wood-framed and plastered in a variety of earth tones, each connected unit has its own entrance to maintain a single-family-unit feel. The development’s offset, interlocking, and set-back rectilinear volumes enhance its close neighborhood feel, hinting at diverse urban uses and functions through the playful intersection of masses, although the project essentially has only a single function. This play of forms creates a terracing effect of sorts, from front protruding volumes that reach down to the streetscape with stoops that provide neighborhood gathering places to set-back rectilinear volumes on top levels that subtly evoke the bell towers of one of the project’s aesthetic touchstones: California Mission architecture. Curb appeal

Curb appeal Public housing projects rarely manage to make affordable materials like plaster truly shine, but Irvington Terrace’s cohesive balance of massing gives its plaster construction the appearance of the permanence of concrete or stone, and its flourishes of detail (like its landscaping and trellised walkways) seem more akin to upscale shopping centers than municipal public housing. “It’s not stamped as a project that looks and smells, shall we say, like a project or a state funded development,” Vasquez says. “It has good curb appeal.”

Public housing projects rarely manage to make affordable materials like plaster truly shine, but Irvington Terrace’s cohesive balance of massing gives its plaster construction the appearance of the permanence of concrete or stone, and its flourishes of detail (like its landscaping and trellised walkways) seem more akin to upscale shopping centers than municipal public housing. “It’s not stamped as a project that looks and smells, shall we say, like a project or a state funded development,” Vasquez says. “It has good curb appeal.” Gill is most known for designing housing projects, primarily in San Diego, for communities that rarely had access to quality housing: recent immigrants, African-Americans, and low-income people. His way of stripping down the details of ornament-laden California Mission style and rendering its essence in raw concrete is reminiscent in Irvington Terrace. Gill’s is a surprisingly explicit Modernist credo, considering that he was most productive from 1908-16, when the historicist California Mission Revival style was most en vogue, and he practiced across the nation before the influential European Modernists in exile made landfall and begin teaching at American universities.

Gill is most known for designing housing projects, primarily in San Diego, for communities that rarely had access to quality housing: recent immigrants, African-Americans, and low-income people. His way of stripping down the details of ornament-laden California Mission style and rendering its essence in raw concrete is reminiscent in Irvington Terrace. Gill’s is a surprisingly explicit Modernist credo, considering that he was most productive from 1908-16, when the historicist California Mission Revival style was most en vogue, and he practiced across the nation before the influential European Modernists in exile made landfall and begin teaching at American universities.