Currier Museum Addition Bulks Up Yet Dematerializes with Glass

Ann Beha Architects join glass and masonry in a subtle expansion of New Hampshire’s Currier Museum of Art

by Zach Mortice

Associate Editor

Summary: The newest galleries in the Currier Museum of Art are subtle and proportional interpretations of the existing masonry buildings. They use glass walls to create expressive visibility corridors and preserve the original plan’s symmetry. The product of a tight budget, this addition doubles the museum’s amount of exhibition space and offers new amenities. Summary: The newest galleries in the Currier Museum of Art are subtle and proportional interpretations of the existing masonry buildings. They use glass walls to create expressive visibility corridors and preserve the original plan’s symmetry. The product of a tight budget, this addition doubles the museum’s amount of exhibition space and offers new amenities.

How do you … design modestly budgeted renovations and additions for a public art museum that are contextual and subordinate to the building’s original design intent?

Can a museum’s original design intent survive an addition that uses a radically different material palette? Can a museum’s original design intent survive an addition that uses a radically different material palette?

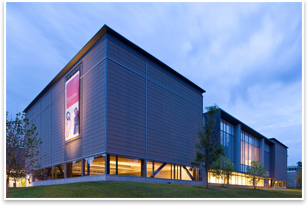

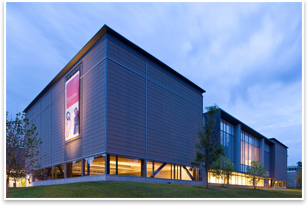

In the example of the Currier Museum of Art in Manchester, N.H., the answer is yes. Ann Beha Architects’ renovation and addition seems to be a case study in how to bridge this very transition. This project employs glass in both added and renovated sections of the Art Deco-verging-on-Neo Classical masonry structure, applying ideas about transparency and the building’s relationship to its surrounding urban fabric to New Hampshire’s only public art museum. Such a material change didn’t trigger formal changes. Ann Beha Architects’ plan reinforces its original classical symmetry and massing, all the while integrating this material rupture into buildings built more than 50 years apart.

Double up Double up

Boston-based Ann Beha Architects completed 70,000 square feet of renovations and additions for the museum, which re-opened in March. The first wing of the building (an Art Deco structure with tautly restrained classical detailing) was designed by the New York firm of Tilton and Githens and built in 1929. Another wing was added by New York-based Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer in 1982. It consists of two crème colored brick porticos with mansard roofs.

Ann Beha’s addition adds three new galleries: a sculpture gallery at the south end of the complex and two special exhibits galleries, one at the east end and one at the west end. The firm placed an all-weather enclosed Winter Garden room in front of the former entrance on the original 1929 building’s south side. The museum’s new entrance is at the building’s north end between the two 1982 additions and next to a sculpture plaza. With a conservative budget of $14 million, Ann Beha doubled the amount of exhibition space.

New faces New faces

None of these new galleries announce themselves with disjunctures of form, and they fit into the original plan subtly. Each new part extends and supports the north-south central visibility axis that organizes the museum.

“I think we were very conscious of using proportions and a kind of modularity that was very classical, and to a certain extent timeless,” say Pamela Hawkes, FAIA, the partner-in-charge of the Currier Museum project.

The visitor’s experience begins with a floor-to-ceiling glass wall that covers the new lobby. This use of glass creates warm and inviting views into the museum, a foil to the heavy and formal masonry of the original building, according to Hawkes.

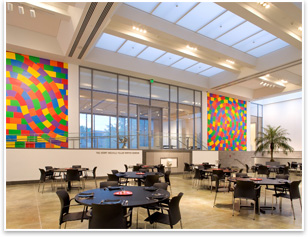

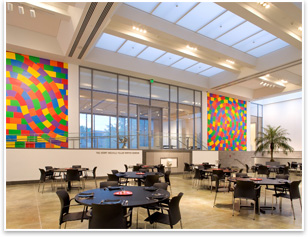

Hawkes and her team enlarged openings in the original building to create view corridors along its central axis. Glass walls are used extensively in the renovated museum to allow for dialogue among pieces in different galleries. “Wherever you are, you’re either looking into an interior space or looking out to the outside,” says Hawkes. “There’s no place where you’re really confined within the building.”

As patrons exit the original 1929 building, they’ll enter the new Winter Garden, a multipurpose space for lectures, performances, and receptions that also contains the museum café servery. The new terra cotta-detailed east and west galleries wrap around the sides of the Winter Garden. The stately and formal limestone façade of the original building is the “community face of the museum to the public,” says project manager Scott Aquilina, AIA. The Winter Garden’s roof is pierced by skylights and supported by four aluminum-clad columns. This mix of Neo-Classical and contemporary textures in a central event space calls to mind Foster and Partners’ glass-roofed atrium at the National Portrait Gallery and Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., though Ann Beha’s project is much smaller in scale and formal experimentation. As patrons exit the original 1929 building, they’ll enter the new Winter Garden, a multipurpose space for lectures, performances, and receptions that also contains the museum café servery. The new terra cotta-detailed east and west galleries wrap around the sides of the Winter Garden. The stately and formal limestone façade of the original building is the “community face of the museum to the public,” says project manager Scott Aquilina, AIA. The Winter Garden’s roof is pierced by skylights and supported by four aluminum-clad columns. This mix of Neo-Classical and contemporary textures in a central event space calls to mind Foster and Partners’ glass-roofed atrium at the National Portrait Gallery and Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., though Ann Beha’s project is much smaller in scale and formal experimentation.

From there, visitors move on to the south sculpture gallery, the rear of which becomes a new public face for the museum and looks back towards the city with a wall of glass that is framed by a Mondrian-like terra-cotta rainscreen.

Ironic contexualism Ironic contexualism

With some irony, Hawkes says preserving the museum’s symmetrical organization allowed the glass wall sections to function better as an interspatial reference-allowing material, as abandoning the plan may have placed obstructions in front of straight sight lines. At the Currier Museum, conservative tastes (Hawkes describes her New England clients as being suspicious of “flash and flummery”) and a narrow budget created an understated addition that is contextual in plan and proportion and contextual still in its use of glass in recognition of the surrounding urbanism. In some ways, it is quite 19th century, pre-dating even the construction of its first wing. But by using glass as an invitation to the civic appreciation of art, it incorporates contemporary ideas about casual spectatorship and democratization of the arts.

|

Summary:

Summary:

Double up

Double up New faces

New faces

Ironic contexualism

Ironic contexualism