Polshek Partnership Restores a Kahn Landmark at Yale Polshek Partnership Restores a Kahn Landmark at Yale

Summary: Polshek Partnership Architects, New York City, has renovated and restored The Yale University Art Gallery, Louis I. Kahn’s first significant commission and considered by many to be his first masterpiece. The Modern building, a recipient of the AIA Twenty-five Year Award and the first of its genre on the Neo-Gothic Ivy League campus, reopened last month in New Haven.

Of prominence was Kahn’s glass-and-metal exterior wall. “It had always been troubled” Hazard says. “In dismantling the wall to replicate it we discovered the sources of some of those problems. There was not enough allowance for thermal expansion and contraction. The stresses in the wall had been so considerable that they had bent the edge slab.” Furthermore, the materials did not suit the building’s museum climate. “From what we were able to analyze, as soon as it got to be about 43 degrees, the wall would start to sweat on the inside,” Hazard says. “Drip pans were installed on the inside of the buildings to catch the condensation.”

The architects went through the laborious process, Hazard says, of designing, testing, tweaking, and retesting a wall to look like the old but that would perform to today’s museum standards. “We are pleased that the wall we put back there looks great, with only one mullion piece on the interior that is deeper than the original wall,” Hazard says. Other improvements To open York Street Court, which had been roofed in the ’70s to create additional gallery space, the designers removed the roof and replaced the window wall that had been destroyed. The restored courtyard now houses Richard Serra’s Stacks. The team also restored and extended the back sculpture garden, moved all the building’s mechanical equipment to the roof or basement to free up the central mechanical core for a larger accessible elevator that can also be used to move larger art pieces, and transformed the first-floor lobby into a media lounge, an inviting information center and gathering place.

“It became clear to us that Kahn, like us, was learning a lot. It was his first major commission. We kept feeling as we were working our way through the building that we’d come to a place where he had had to stop and figure out how he was going to resolve a condition, say something that wasn’t quite consistent with the rest, and found a way to turn something that didn’t initially seem ideal into a beautiful resolution. “It was an incredibly satisfying experience to feel that over time we were partnering with Louis Kahn.” Hazard says they constantly felt Kahn’s presence. “It was sort of a joke on the team. When something wouldn’t work out we would say: ‘Well, I guess Lou didn’t like that idea.’” |

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Kahn’s Yale Center for British Art Receives Twenty-five Year Award

Visit the Yale University Art Gallery Web site.

Duncan Hazard, AIA, is Polshek Partnership Architects’ lead planner for the Yale Arts Area, and a university alum. James Polshek, FAIA, received his MArch from Yale and was in the first class of students to be educated in Kahn’s Art Gallery, which at the time housed the architecture studio.

Louis Kahn designed what would become the main facility of the Yale University Art Gallery while he was a visiting critic at the Yale School of Architecture (1947–57). The curators consider the building “the largest piece of artwork in their collection,” Hazard says. The gallery is across Chapel Street from the Yale Center for British Art, which Kahn designed in 1974, and the last of his buildings on which construction was begun during his lifetime. Together, the two museums stand in poignant dialogue, the architects note, not only bracketing the great architect’s career, but also providing a profound aesthetic experience. The Yale Center for British Art received the AIA Twenty-five Year Award in 2004. The Yale University Art Galley received the AIA Twenty-five Year Award in 1979.

Images:

1)

North side and upper courtyard, 2006. Sculptures in the courtyard are For D.G., by Tony Smith and Untitled, by Joel Shapiro. Photo © Yale University Art Gallery. Photo: Elizabeth Felicella.

2) Second floor; interior view of African art installation, 2006. Photo © Yale University Art Gallery. Photo: Elizabeth Felicella.

3) View of staircase, 2006. Photo © Yale University Art Gallery. Photo: Elizabeth Felicella.

4)

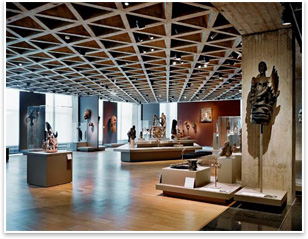

Second floor, interior view of Asian art installation, 2006.

Photo © Yale University Art Gallery. Photo: Elizabeth Felicella.