Breaking

Out of Jail

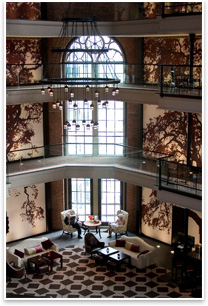

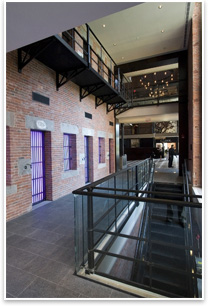

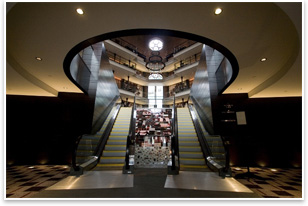

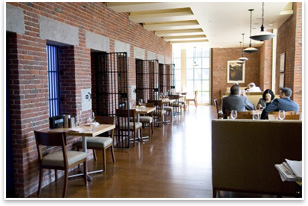

Summary: Boston's Charles Street Jail, a national historic landmark sited downtown overlooking the Charles River, has been transformed into the luxurious, $110 million Liberty Hotel by Cambridge Seven Associates. The design incorporates historically significant portions of the existing building, including its granite exterior, windows, a 90-foot rotunda, cupola, brick cells, and interior catwalks. In addition to converting the cells into luxury rooms, the design also incorporates a new 16-story tower. The hotel opened on September 5 and, so far, is proving to be a development catalyst within Boston’s Beacon Hill neighborhood.

“I call it transformative reuse rather than adaptive reuse,” says principal-in-charge Gary Johnson, AIA, at Cambridge Seven Associates. “The project didn’t just turn this building into a different use—we’ve transformed a section of Boston. The building was derelict and walled off, but is now the center of a transformed neighborhood. The city has done street improvements and built a new transportation center, and the hospital built a new fronting onto the restored jail. This project has been the best kind of reuse catalyst, bringing 24/7 life and a whole new kind of energy into the neighborhood.” An unusual hospitality experience

The next step was to clean out the old jail. “After we got the junk out of it, we took some of the roofs off so we could access the building with hoists,” explains Johnson. “Because some of the roofs were more original to the building than others, we chose the newer ones to take off. We took the cell blocks out floor-by-floor and piece-by-piece. They were three-foot brick walls, with eight-foot-long stone slabs. We did foundation work and installed new floors.” Johnson says the jail was built in the marsh lands of the Charles River. “The jail was built on Boston’s blue clay, notorious for bad foundations. They built it on 85-foot-long oak piles. When we explored the piles, the tops of them looked like they were freshly sawed. Once you cleaned them off, they were as pure as if you cut a tree today. And with all the waterfront and construction changes, the building didn’t have but one crack in it.”

A new cupola is a reproduction of one envisioned when the jail was first designed. Surrounding the rotunda are four chimneys, one per side, and granite chimneys on the north and south wings that are actually part of the ventilation systems for the cells. “The big problem was inside,” explains Johnson. “The building is 100 percent solid masonry with no air space. To put new finishes on the walls and still control the moisture, we put a gap in the air space so water vapor can be mechanically wicked. For the rotunda, which is exposed brick, we decided to leave the brick as the finish material. It had about six coats of paint on it. We decided to take the paint off because the water migration through the brick completely destroyed the paint. To control moisture from getting on the brick in the rotunda, we cleaned the original wooden trusses, removed shabby steel supports and a plaster ceiling from 1949 when the original cupola was taken down, and added new steel supports sympathetic to the original wooden trusses.”

Each guest room combines 8-foot x10-foot cells made of brick walls, stone floors, stone ceilings, and two-foot-wide doors and windows. “We left the bars on the windows in the ballroom and some of the meeting rooms,” notes Johnson. “For the rooms, we cut the bars off but ground them down smooth with the brick. You can see clearly where the bars were.” An 18-foot-tall brick wall that once surrounded the jail’s

courtyard was torn down and replaced by a 2.5-foot granite wall.

A secret vegetable garden was created between the old jail and new

tower. Johnson retained a doorway, padlock, and its granite surrounds

that once went into a quarantine area. The hotel features a 2,000-square-foot

presidential suite with views, a restaurant called Clink, a bar called

Alibi, and another restaurant that will open in January called Scumpo, which means “escape” in Italian. “The developers

are playing a fun game,” says Johnson. “It’s a

jail, but—wink, wink—it’s fun, hip, a great location,

and a great place to spend the night. It’s the first time you

can leave the building on your own free will.” |

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

home

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Library

of Congress Gives Hillside Bunker a New Use

› Museum

Reasserts Presence on Olmsted Park