Between Home and Hospital by Zach Mortice

Summary: The Residential Treatment Center at Lawrence Hall in Chicago provides the safety and security appropriate for a child welfare agency that treats at-risk children while still offering a warm and reassuring community-based experience. Its design, as well as previous Lawrence Hall residential buildings, has adapted prevailing urbanism models to this particular youth treatment setting. It is the first part of a three-phase renovation of the entire campus, all by local architecture firm McBride Kelley Baurer.

Lawrence Hall’s new center is the first part of a three-phase master plan by the Chicago firm of McBride Kelley Baurer. The second phase will include a school with vocational classrooms, computer labs, and outdoor study spaces. The last phase will be a new administrative building and outdoor recreation facilities. Lawrence Hall, which cares for 1,100 children, sits on a triangular seven-acre site in northwest Chicago. McBride Kelley Baurer’s master plan will create six new buildings that huddle around a central courtyard.

Problems and solutions

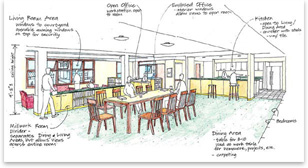

“What we didn’t have was a treatment facility that would really deal with the most traumatized youth in a treatment setting that was homelike but created a sense of community that focused on the safety of the kids,” says Hollie. High-impact drywall is used for the walls, and the floors are carpeted or tiled with vinyl. To accommodate the eight adolescents who will use the units’ shared spaces, the architects made common rooms large. To avoid the feeling of an anonymous warehousing institution, the architects broke up these big rooms with cabinetry dividers and different ceiling heights. Jack Kelley, AIA, a principal at McBride Kelley Baurer, says he wanted to design spaces where kids could do separate things while not having to be in separate rooms. The architects avoided glass enclosures positioned as surveillance posts for staff in favor of open-planned workstations. “The subtlety of that is important,” says Kelley.

“The suburban model was objects in space—a lot of area around each building,” Kelley says. “That creates the problem of the staff and kids not seeing each other as they’re passing.”

“We’re a leader in this,” says Hollie. “We have other agencies and entities that [came] to the open house to be ‘spies.’”

|

||

Copyright 2008 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

home

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› TONA Upgrades and Expands at Covenant House New York

› Three LEED Buildings Grace One Hospital Campus

› Themed Store Makes Toy Shopping Child’s Play

› Walt Disney Family Museum Reuses Presidio Buildings

Visit McBride Kelley Baurer’s Web site.

Visit Lawrence Hall Youth Services’ Web site.

Captions

Lawrence1. The Residential Treatment Center at Lawrence Hall in Chicago by McBride Kelley Baurer provides the safety and security for at-risk children. Courtesy of the architect.

Lawrence 2. Lawrence Hall, which cares for 1,100 children, sits on a triangular seven-acre site in northwest Chicago. Courtesy of the architect.

Lawrence 3. Architect’s rendering of the open communal area. Courtesy of the architect.

Lawrence 4. The architects broke up the big rooms with cabinetry dividers and different ceiling heights. Courtesy of the architect.

Lawrence 5. The architects broke up these big rooms with cabinetry dividers and different ceiling heights. Courtesy of the architect.

Lawrence 6. The 143-year-old institution is etching out a new paradigm for residential youth services living. Courtesy of the architect.

How do you . . .

How do you . . .  As a child welfare agency that has been around since the Civil War, Lawrence Hall Youth Services in Chicago has seen prevailing design solutions come and go with the decades. Since 1865, it has provided shelter, education, and treatment for children in Illinois dealing with severe emotional and behavioral challenges from trauma, abuse, and neglect. As a mirror of the same design approaches that have been shaping cities for the past 140 years, Lawrence Hall’s campus has worked its way through imposing Beaux Arts institutionalism and mid-20th century suburbanization. In February, it celebrated the opening of its newest replacement to its aging facilities—a condominium-style Residential Treatment Center that balances institutional safety and security with residential comfort.

As a child welfare agency that has been around since the Civil War, Lawrence Hall Youth Services in Chicago has seen prevailing design solutions come and go with the decades. Since 1865, it has provided shelter, education, and treatment for children in Illinois dealing with severe emotional and behavioral challenges from trauma, abuse, and neglect. As a mirror of the same design approaches that have been shaping cities for the past 140 years, Lawrence Hall’s campus has worked its way through imposing Beaux Arts institutionalism and mid-20th century suburbanization. In February, it celebrated the opening of its newest replacement to its aging facilities—a condominium-style Residential Treatment Center that balances institutional safety and security with residential comfort.  The four-story, 50,000-square-foot residence building will be a permanent home for 48 children with intensive treatment needs. The ground floor (clad in concrete) contains a cafeteria, counseling spaces, and medical offices, with an abundance of windows and natural light. The top three floors (in red brick, with aluminum-clad windows) are divided into six condo-style residential units, each for eight kids and a staff supervisor. Each child has his or her own bedroom, but they share common living spaces and kitchens.

The four-story, 50,000-square-foot residence building will be a permanent home for 48 children with intensive treatment needs. The ground floor (clad in concrete) contains a cafeteria, counseling spaces, and medical offices, with an abundance of windows and natural light. The top three floors (in red brick, with aluminum-clad windows) are divided into six condo-style residential units, each for eight kids and a staff supervisor. Each child has his or her own bedroom, but they share common living spaces and kitchens.  Mary Hollie, Lawrence Hall’s CEO, says that the cottage-style residences were made obsolete when Lawrence Hall acquired single-family homes beyond the campus. Many of the agency’s wards needed treatment that was much more intensive than it had been in the past, and these freestanding homes didn’t facilitate this increased need.

Mary Hollie, Lawrence Hall’s CEO, says that the cottage-style residences were made obsolete when Lawrence Hall acquired single-family homes beyond the campus. Many of the agency’s wards needed treatment that was much more intensive than it had been in the past, and these freestanding homes didn’t facilitate this increased need.  A new model

A new model  Leaders

Leaders