|

Washington’s Newseum Goes to Press Polshek Partnership’s museum is a testament to the media and the First Amendment

Summary: Polshek Partnership’s Newseum, which opened April 11, uses a material and formal language of Modernist industrial glass and steel to communicate the concept of media transparency and the professionalization of the decentralized field of journalism. Its site and materials further distinguish it as a symbol of the institutional watchdog function of journalism.

This contextual disruption is only one of the ways Polshek Partnership’s museum embodies the final professionalization and standardization of the media; a journey that changed journalists, or at least the perception of them, from grubby, hard-boiled craftspeople to independent and white-collared professionals. The glass façade and multi-planed design makes the Newseum stand alone in stolid, stone-clad Washington, which arguably can be counted as a step forward for progressive Modernism in the city and an embodiment of the presses’ changing role in contemporary society.

The Newseum’s exterior is composed of interlocking horizontal and vertical rectilinear masses, organized in a framework of three layers that its designers liken to the layers of a newspaper. From the layer closest to the Pennsylvania Avenue back, each section offers more and more solar shielding for sensitive exhibits. The front-most volume contains a massive glass atrium window set back within the structure by 30 feet. A translucent white glass proscenium frames this window in the museum, and continues onto the building’s tip of the hat to stone Washington monumentality: a 74-foot-tall tablet made of two-toned Tennessee marble with the words of the First Amendment engraved on it. Horizontal and vertical striations abound, giving the museum’s façade a Mondrian-like geometric complexity.

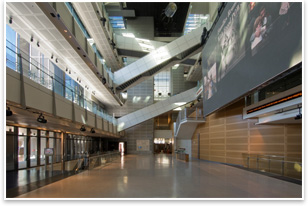

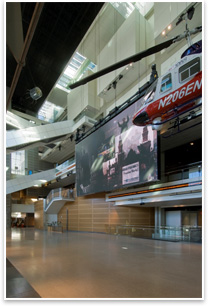

From here, the museum reveals its formal allusions to the media and journalistic transparency. Polshek says that early in the design process, he realized that glass has had a long tradition of mediating how people receive the news, via computer screens, television, or the bulbous glass domes of a ticker-tape machines. As Polshek’s firm has explored in other projects, glass is a direct metaphor for external and internal media transparency and independence. The notion of internal transparency is reinforced by the interior views the museum offers. Elevated walkways, floating stairs and bridges, and glass partitions allow for surprising sightlines into various exhibits and spaces across the museum’s six public floors. One glass-walled room allows visitors to observe the museum’s engineers as they program the video and computer exhibits.

All of this demonstrates that the Newseum is heavily invested in the idea of journalism as a professionalized field populated by transparently non-biased technocrats who are inherently wired to information technology news cycles, not a clubby, rabble-rousing mob of word-machinists with calloused hands. The Newseum is probably the last signpost on the road of this transition: a precision, monumental machine for the professional codification of journalism and press freedom. The back-slapping warmth of the cigar smoke-filled room isn’t to be found in this cool, politely curious museum. Some in the media (including old-school denizens of such places) are disturbed by this monumentality. Storied New York columnist Jimmy Breslin called the idea of the original museum “sickening ... You’re supposed to be scruffy and despised. You’re not supposed to be honored.”

Polshek says he sees narrative content as vital to this building, and to all of his work as well. “I believe that every building has to have a narrative, every building has to have a story, and those stories have to be woven in such a way that they’re given to multiple interpretations,” he says.

Polshek’s museum isn’t ethereal, but it is mutable and timely. Some exhibits are designed to change every day. The giant media screen in the Great Hall of News shows breaking news, while tickers run headlines constantly. It contains two television studios, and the glass atrium windows always show a procession of humanity learning about their First Amendment rights. This contextually daring use of glass isn’t about dematerialization or mystic ambiguity. It’s about commenting as directly as possible on the fundamental need for an honest gatekeeper to the information that fuels a modern and diverse democracy.

|

||

Copyright 2008 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

Recent related

› Journalism 3.0—By Polshek Partnership

› Polshek Partnership Restores a Kahn Landmark at Yale

› Museum Courtyard Glides Through the Ages

› Smithsonian American History Museum Undergoing Makeover

› National Law Enforcement Museum to Grace Nation’s Capital

Visit the Newseum’s Web site.

Visit Polshek Partnership’s Web site.

Did you know . . .

A 2006 survey by the McCormick Tribune Freedom Museum found that 22 percent of Americans could name all five of the cartoon Simpsons family, but only one in 1,000 could name all five freedoms guaranteed in the First Amendment: worship, speech, press, petitioning the government, and assembling peacefully.

Photos

1. View from West Wing National Gallery.

Photo by Eric Taylor © EricTaylorPhoto.com

2. View east to Capitol.

Photo © Robert Young/Polshek Partnership.

3. View to northwest.

Photo by Eric Taylor © EricTaylorPhoto.com.

4. View of bar 2.

Photo © Robert Young/Polshek Partnership.

5. Atrium looking west.

Photo by Eric Taylor © EricTaylorPhoto.com.

6. Atrium looking west.

Photo by Eric Taylor © EricTaylorPhoto.com.

7. Forum Theatre.

Photo by Eric Taylor © EricTaylorPhoto.com.