Journalism 3.0—By Polshek Partnership

The third building in the Newhouse School of Public Communications takes it into a world of collapsing boundaries and converging media.

by Zach Mortice

Associate Editor

How do you . . . design a journalism school that acknowledges the press’s role as the holder of a transparent public trust through materiality, yet is still contextually responsive to vastly different material choices in the surrounding architecture? How do you . . . design a journalism school that acknowledges the press’s role as the holder of a transparent public trust through materiality, yet is still contextually responsive to vastly different material choices in the surrounding architecture?

Summary: Polshek Partnership’s Newhouse III addition to Syracuse University’s journalism school makes literal and symbolic comments on the role of the press, as the words of the First Amendment are printed in laminated glass on the façade and extensive use of glass refers to the press’s responsibility to practice and promote democratic institutional transparency. The new addition acknowledges the previous Newhouse buildings’ architectural traditions by gradually changing its volumetric language and materiality.

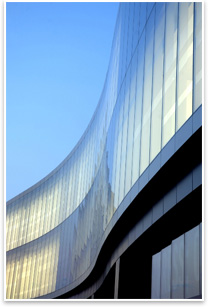

From the east to the west, the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University gradually reveals itself and its inner workings, from abstract concrete-clad Modernist heft to a contemporary, shimmering, and transparent curve of curtain-wall glass. This story, told over three buildings in 40 years, is an apt metaphor for the development of the subject matter taught at this premiere school of journalism: the story of an opaquely misunderstood and workman-like trade maturing into a profession responsible for maintaining a transparent public trust in the institutions on which it reports and in its own operations. Polshek Partnership Architects of New York City have had the opportunity to tell the last part of this story with the opening of the 75,000-square-foot Newhouse III addition, which opened to students in September. From the east to the west, the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University gradually reveals itself and its inner workings, from abstract concrete-clad Modernist heft to a contemporary, shimmering, and transparent curve of curtain-wall glass. This story, told over three buildings in 40 years, is an apt metaphor for the development of the subject matter taught at this premiere school of journalism: the story of an opaquely misunderstood and workman-like trade maturing into a profession responsible for maintaining a transparent public trust in the institutions on which it reports and in its own operations. Polshek Partnership Architects of New York City have had the opportunity to tell the last part of this story with the opening of the 75,000-square-foot Newhouse III addition, which opened to students in September.

“I felt that it was very important to take a can opener to the programs and just say: ‘Look—this is what we do!’” says Tomas Rossant, AIA, the building’s designer at Polshek. “It’s this notion that nothing is under wraps anymore.” “I felt that it was very important to take a can opener to the programs and just say: ‘Look—this is what we do!’” says Tomas Rossant, AIA, the building’s designer at Polshek. “It’s this notion that nothing is under wraps anymore.”

Symbol and stature

Perennially ranked as one of the world’s top journalism schools, the Newhouse campus already had architecture by world-class architects, but not an appropriate icon. “It was an institution that didn’t have a building symbol comparable to its stature,” says Rossant.

The school’s first building, a concrete Brutalist structure representative of architect I.M. Pei’s work in the ‘60s, was completed in 1964. SOM completed the Newhouse II in 1974, adding another pre-cast concrete structure that Rossant says mimics the “brooding” masonry of Pei’s Newhouse I. The school’s first building, a concrete Brutalist structure representative of architect I.M. Pei’s work in the ‘60s, was completed in 1964. SOM completed the Newhouse II in 1974, adding another pre-cast concrete structure that Rossant says mimics the “brooding” masonry of Pei’s Newhouse I.

These first two buildings, Rossant says, lacked programmed and unprogrammed spaces for informal social interaction. Circulation patterns were also awkward and circuitous, and the opaque materials of Newhouse I and II stymied public interaction. The school “needed to bolster its sense of community,” says Rossant. “It needed a kind of social and intellectual glue.”

A bridge with lounge space between the first two buildings improved some of the circulation problems. A plaza surrounds Newhouse I, and Polshek’s addition connects the new building to this plaza level and two levels below ground. It connects to Newhouse II at every floor. Newhouse III increases the useable space of the school by a third and contains classrooms, offices, an exhibition gallery, a small cafeteria, and the school’s first dedicated auditorium. A bridge with lounge space between the first two buildings improved some of the circulation problems. A plaza surrounds Newhouse I, and Polshek’s addition connects the new building to this plaza level and two levels below ground. It connects to Newhouse II at every floor. Newhouse III increases the useable space of the school by a third and contains classrooms, offices, an exhibition gallery, a small cafeteria, and the school’s first dedicated auditorium.

Across the school, across media

The Newhouse III building is itself divided into three sections from east to west, and each part works to change the site’s formal and material dialogue gradually. Closest to the SOM and Pei buildings on the west side is a contextually responsive pre-cast concrete bar-shaped building that contains elevators, stair towers, and mechanical space. Next is a transitory three-story atrium that connects to the new building’s signature element: a 275-foot curving glass curtain-walled rectangular volume with the words of the First Amendment printed on it. Rossant says this dynamic form reflects the progressive nature of the journalism school’s mission. These sloping, curvilinear forms also provide a rich contrast to the bulky, rectilinear opaqueness of the rest of the school.

Inside Newhouse III, the liberal use of glass aids students’ and faculty’s ability to see across different floors and between different journalistic fields of study in the hopes that this will increase cross-disciplinary collaboration. Rossant says fostering this level of social interaction will help students prepare for a digital media world where traditional media (print, radio, television) are converging and blending together in electronic formats. Rossant’s idea was to create a space that breaks down the notions of departments (the Newhouse School teaches magazine journalism, news journalism, public relations, broadcast journalism, advertising, photography, and graphic arts) focused on a medium that works “in an insular way—that there’s just advertising, that there’s just PR, that there’s just print journalism. That’s all going away, so the building itself, in terms of internal organization, had to foster a kind of breaking down of vertical silos.” Inside Newhouse III, the liberal use of glass aids students’ and faculty’s ability to see across different floors and between different journalistic fields of study in the hopes that this will increase cross-disciplinary collaboration. Rossant says fostering this level of social interaction will help students prepare for a digital media world where traditional media (print, radio, television) are converging and blending together in electronic formats. Rossant’s idea was to create a space that breaks down the notions of departments (the Newhouse School teaches magazine journalism, news journalism, public relations, broadcast journalism, advertising, photography, and graphic arts) focused on a medium that works “in an insular way—that there’s just advertising, that there’s just PR, that there’s just print journalism. That’s all going away, so the building itself, in terms of internal organization, had to foster a kind of breaking down of vertical silos.”

“Congress shall make no law ...” “Congress shall make no law ...”

The motif of using glass to comment on the media’s role as a transparency-enforcing institutional watchdog is present in other Polshek projects. In all of these buildings, the act of looking through glass walls into the inner workings of a complex organization is a visual metaphor for how journalists are asked to reveal the world to their readers and viewers; with honesty and transparency that results from the breaking down of institutional barriers. The journalism-themed Newseum museum in Washington, D.C., and the firm’s WGBH radio building in Brighton, Mass., share this element. Much of the design work for these three buildings was done simultaneously, though the Newseum project began first. The WGBH building (which Rossant also designed) and Newhouse III opened within two weeks of each other.

These designs influenced each other in unforeseen ways as well. When David Rubin, dean of the Newhouse School, heard of the plans to put the words of the First Amendment on the front of the Newseum, he asked Rossant to do the same for his building in Syracuse. Rossant initially balked at this, but Rubin was steadfast. On the Newseum, the 45 words of the First Amendment are engraved on a 60-foot high stone plane attached to the façade, but in the Newhouse III building, the words wrap around the long, horizontal glass façade in laminated glass, which Rossant likens to a “modern interpretation of a frieze or entablature” in Classical architecture.

Above these words, the façade is tempered with ceramic fritting. Linear, graphic patterns of unfritted panels run across the curtain wall in a dynamic display of kinetic motion. One person told Rossant that it looked like rolls of newsprint racing along a printing press.

“That was such a perfect thing,” he says, pleased with the symbolic interpretation. |