Museum Courtyard Glides Through the Ages

Once again, Foster + Partners prove their mastery of the historic public sphere

by Zach Mortice

Associate Editor

How do you . . . carefully renovate a famed historic building’s courtyard while adding an atrium that effectively evolves its contemporary form from Neoclassical surroundings? How do you . . . carefully renovate a famed historic building’s courtyard while adding an atrium that effectively evolves its contemporary form from Neoclassical surroundings?

Summary: The Robert and Arlene Kogod Courtyard at the National Portrait Gallery and Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., is the latest example of Foster + Partner’s approach to designing historic renovations that respect the original building’s history without bowing to it in subservience. The steel-framed atrium draws its form from the Greek Revival Old Patent Office that surrounds it. It engages the building in an energetic discourse on the progression of human knowledge. The courtyard below features lush landscaping and unadorned stonework and also works in concert with the adjacent facades.

At the media preview of the new Robert and Arlene Kogod Courtyard at the National Portrait Gallery and Smithsonian Museum of American Art, mild platitudes on the philosophical nature of historical renovations were offered left and right—a common experience in Washington, D.C., where so much of the notable architecture is concerned with democracy’s roots in 18th-century Neoclassicism and its continual upkeep. Marc Pachter, director of the National Portrait Gallery, talked about “democracy’s living room.” Foster + Partner’s Spencer de Grey spoke of a “dialogue between the old and the new.” At the media preview of the new Robert and Arlene Kogod Courtyard at the National Portrait Gallery and Smithsonian Museum of American Art, mild platitudes on the philosophical nature of historical renovations were offered left and right—a common experience in Washington, D.C., where so much of the notable architecture is concerned with democracy’s roots in 18th-century Neoclassicism and its continual upkeep. Marc Pachter, director of the National Portrait Gallery, talked about “democracy’s living room.” Foster + Partner’s Spencer de Grey spoke of a “dialogue between the old and the new.”

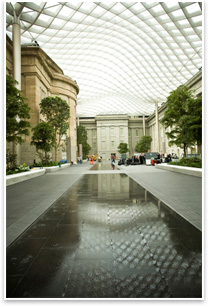

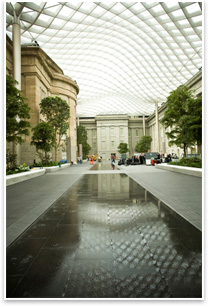

Foster + Partners’ new steel space-age saddled courtyard—placed in the midst of Robert Mills’ Old Patent Office, one of the nation’s most celebrated Greek Revival buildings—itself seems to speak at length about Classical geometry, Greco-Roman philosophy, aerospace engineering, and theoretical physics. The atrium’s undulating form’s cohesive match with the adjacent classical porticos and pediments reaffirms the connection between the sciences and the arts throughout antiquity. The enthusiasm of this conversation infects all of the 28,000 square feet of the courtyard, which completes an invigorating public space that has shifted from focusing on American innovations to celebrating the innovators.

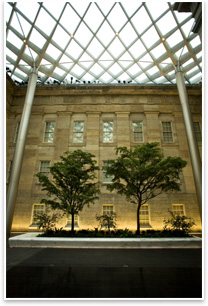

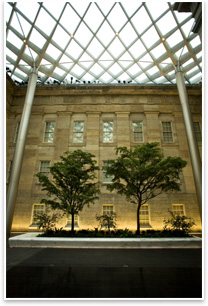

The south sandstone wing of the Old Patent Office was designed by Mills and built from 1836 to 1842. Conceived of as the new nation’s “temple of innovation,” it would document and protect the intellectual capital of the grand new democratic experiment. Thomas U. Walter completed the granite north and west wings before the Civil War. In 1953, the building was nearly leveled to make way for a parking lot. President Eisenhower saved the building from destruction, and it reopened as the National Portrait Gallery and Smithsonian American Art Museum in 1968. Another round of renovations was completed in 2006, and, finally, the $63 million Kogod Courtyard opened last month. The south sandstone wing of the Old Patent Office was designed by Mills and built from 1836 to 1842. Conceived of as the new nation’s “temple of innovation,” it would document and protect the intellectual capital of the grand new democratic experiment. Thomas U. Walter completed the granite north and west wings before the Civil War. In 1953, the building was nearly leveled to make way for a parking lot. President Eisenhower saved the building from destruction, and it reopened as the National Portrait Gallery and Smithsonian American Art Museum in 1968. Another round of renovations was completed in 2006, and, finally, the $63 million Kogod Courtyard opened last month.

In motion, through space and time In motion, through space and time

The sleek steel grays, whites, and blacks of the courtyard animate the richly textured surrounding walls, especially the warm sandstone south façade and its narrow portico and squat pediment above. The steel-framed atrium connects to the original building’s roof past the visible edges of the courtyard, making it an all-weather space. Actually, the atrium is entirely supported by eight aluminum-clad columns, four each on the north and south side. This approach was deemed necessary to protect the venerable Patent Office while the museum was in operation and the courtyard was being built simultaneously. The project went from sketch to reality in only three and a half years—another measure of Foster + Partners well-honed prowess with historical renovation projects.

As the museum’s literal and foundational Neoclassical forms rise up to the atrium, they are transformed by Foster + Partners’ design into contemporary equivalents. The blocky symmetry of the museum’s central section and less prominent opposing wings become an 86-foot-tall smoothly flowing central vault with opposing diminutive vaults on each side. There are 864 glass panels that make up the atrium, and no two are the same. The atrium appears to float atop its supports, and its waving profile calls to mind forces that the ancient Greek builders Mills studied might have contemplated and invented myths about: models of black holes, air currents, and tidal waves. Walking through the courtyard, the curves of the atriums’ vault supports alter their density and texture as the viewer’s perspective changes, creating a sense of spatial acceleration appropriate to such elemental models. As the museum’s literal and foundational Neoclassical forms rise up to the atrium, they are transformed by Foster + Partners’ design into contemporary equivalents. The blocky symmetry of the museum’s central section and less prominent opposing wings become an 86-foot-tall smoothly flowing central vault with opposing diminutive vaults on each side. There are 864 glass panels that make up the atrium, and no two are the same. The atrium appears to float atop its supports, and its waving profile calls to mind forces that the ancient Greek builders Mills studied might have contemplated and invented myths about: models of black holes, air currents, and tidal waves. Walking through the courtyard, the curves of the atriums’ vault supports alter their density and texture as the viewer’s perspective changes, creating a sense of spatial acceleration appropriate to such elemental models.

De Grey says the structure takes advantage of the arches’ natural efficiencies and strengths. A flat roof would have required more steel to reinforce. “Every member of the roof is acting structurally,” he says.

Stone and water

Below the atrium, the landscaped courtyard features heavy, bold forms that complement the surrounding Federal-style architecture. Kathryn Gustafson, of Gustafson Guthrie Nichol, landscaped the site, and it features marble planters and plinths filled with temperate trees, ferns, and shrubs. The courtyard floor’s most striking feature is the water fountain, or “scrim” that runs nearly the length of the entire floor. This feature runs water over an imperceptibly tilted black granite block, creating a thin, reflective sheen of water that’s a fraction of an inch deep. This wet stone surface amplifies every bump and grain of the adjacent sandstone and granite walls.

Reimagining history Reimagining history

The Kogod Courtyard is a programmatic recreation of Lord Foster’s work on the Great Court of the British Museum in London. The firm is also working on a vaguely similar project for the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, where they’re building a self-contained glass box within the museum’s courtyard. As stated on their Web site, the charter for this project is likewise to establish “a creative dialogue between the old and the new.”

The Washington, D.C., atrium exists on a smaller scale than many of Foster + Partner’s trademark historic renovation projects, including the German Reichstag in Berlin or the Hearst Headquarters in New York City. But regardless of size, the Robert and Arlene Kogod Courtyard reaffirms Foster + Partners’ penchant for creating enlivening public spaces that use the evolution of democracy as their reference text; from the flashpoint history of Germany’s Weimar-era Reichstag to the Hearst’s machinations for control of the burgeoning Fourth Estate and the ideas about the sovereignty of knowledge in a society of equals embodied by the former Patent Office. |