| In Contemplation of the Cul-de-Sac A Modern museum floats up from the Midwestern suburbs

Summary: Designed as a series of gateways that lead visitors into an art-filled campus, the Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art in Overland Park, Kan., is an austere, Modernist space that is informed by its suburban setting. Though calm and un-iconic, the museum is easily recognized by its two displaced volumes and dramatic cantilever. The new building is part of a museum building boom that is especially impacting smaller cities in the nation’s interior.

This impression was not lost on Kyu Sung Woo, FAIA, and his Cambridge-Mass.-based firm, who were hired to design the museum that now houses this collection, the Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art. “I’ve never seen any place where daily life and art interact that intensely,” he says. Gateways

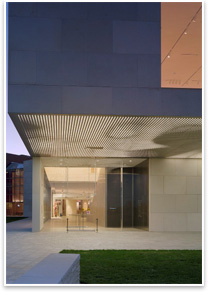

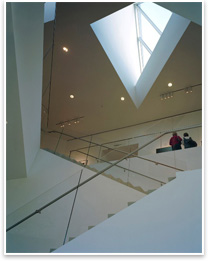

The museum’s site is on the edge of the sprawling 234-acre suburban Kansas City campus. The Nerman Museum is backed into two other facilities and connects (via an atrium) to one of them. Limestone retaining walls reach out from the museum entrance and define movement patterns and boundaries for the visitor, while they simultaneously pull art patrons into the museum’s most striking feature: a 22-foot cantilever that hangs over the museum entrance. On the underside of the cantilever is a permanent LED light installation by artist Leo Villareal, which acts as a bridge between the art inside the museum and the art outside. Just as the museum is a gateway to the campus, Woo says the cantilever is a gateway to the museum. It’s the end point of a shoebox-shaped floating mass that hovers above the museum’s first floor. This mass draws its sense of buoyancy from the glass panels that line the lower floor where the lobby is located. On the opposite side, the cantilevered mass sinks into the lower volume. In one of the few flourishes in the succinctly Modern and minimalist museum, a single, tall window looks out from the end of the cantilever—a portal for the silent witness of artistic contemplation.

White limestone (present at the site) is the primary façade material. This creates a sharp contrast to the adjacent red brick buildings. Inside, long, slitted skylights bring natural light into nearly every one of the galleries. A 200-seat auditorium, museum shop, café, and classroom space fill out the rest of the 41,600-square-foot museum.

Nationally, a museum building boom is changing the cultural landscape of many cities. In October, the Washington Post reported that a 2006 survey by the American Association of Museums found half of the respondents reported they had begun or recently completed an expansion. Smaller cities in the nation’s interior have been leading this charge with museum expansions, like Daniel Libeskind’s Denver Art Museum, Herzog and de Meuron’s Walker Art Center expansion in Minneapolis, Zaha Hadid’s Rosenthal Center for Contemporary Art in Cincinnati, and Santiago Calatrava’s Milwaukee Art Museum expansion. Far from the urban cores that these buildings inhabit, the Nerman Museum’s suburban context make it, in some ways, the leading edge of this boom. |

||

Copyright 2008 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Holl’s Luminous Boxes Shine of Kansas City

› Cultural Corner Stone Anchors Grand Rapids Revitalization

› AIA Kansas City Honor Royal Designs

› Mississippi Gets a Gehry that Lounges with the Trees

Visit Johnson County Community College online.

See Kyu Sung Woo Architects’ Web site.