| Mississippi Gets a Gehry that Lounges with the Trees An architect and a potter who both see their work as art not craft converge in Biloxi

Summary: Frank Gehry’s Ohr-O’Keefe Museum of Art splits five different museum spaces into small, separate buildings that relate and collaborate with the site’s landmark oak trees. The stainless steel-paneled Ohr Gallery pods house the pottery of its namesake George Ohr and demonstrate Gehry’s most quintessential element of the museum campus. Some of the other buildings take cues from local vernacular forms. Construction of the museum was interrupted by Hurricane Katrina, and today elevated construction costs jeopardize the progress of the museum.

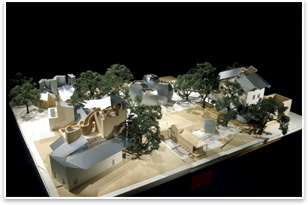

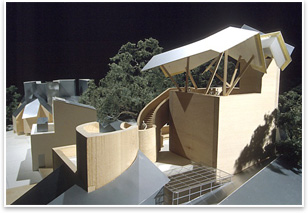

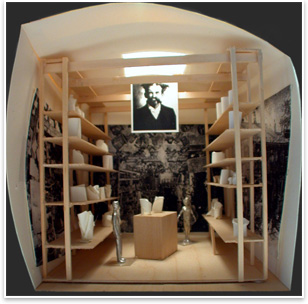

Gehry’s $30 million museum campus is a series of five small buildings that will “dance with the trees” and make lush foliage an equal partner in the architect’s singular design. These five buildings will make up 25,000 square feet of habitable space spread out on a four-acre site. The campus will feature a welcome center, an African-American gallery of folk art, a classroom and studio space called the Center for Ceramics, a contemporary arts gallery, and the George E. Ohr Gallery. The museum campus’s most striking building is the Ohr Gallery. It consists of four single-room “pods” that will house the work of George Ohr, the eccentric, preternaturally self-aware and self-styled “Mad Potter of Biloxi.” Each pod is composed of four 30-foot sides of stainless steel that have been subtly twisted in place around each other, and they resemble nothing so much as leaves taken from Gehry’s own tree of radically exuberant forms. These steel panels look as though they might have fallen off his show-stopping facades for the Guggenheim in Bilbao or the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles; leaves disturbed in his “dance with the trees” that have settled comfortably under expansive branches. Museum Executive Director Marjie Gowdy says this modest and small-scale approach has “captivated the community.”

The roof of the Center for Ceramics peeks out over the tops of the oak trees, but the rest of the plan lets nature be the most prominent and defining design element. A former residential-scaled neighborhood, the museum is a place where architecture is slotted into landscaping, not the other way around. Only seeing the buildings without the context of the trees is "only seeing half the design," says Joey Crain, AIA, whose local firm Guild Hardy is the museum's architect of record. "The cost that went into the construction and design just because of the trees is enormous," says Zamora. He estimates that up to 20 percent of the project’s design time and construction costs were consumed by responsible integration of the trees into the plan. For their design models, Gehry and Partners surveyed branch lengths and built the galleries on top of pilings so that they wouldn't disturb root systems.

The one building on the campus Gehry did not design provides historical and vernacular design direction for the rest of the museum facilities. The Pleasant Reed Interpretive Center is a relocated and reconstructed house, originally built and financed by Pleasant Reed, an emancipated slave. This humble camelback shotgun house’s gabled roof is a repeated motif in the Center for Ceramics and the welcome center. Zamora points this out as a binding element in the design, especially the use of the open shoo-fly roof on the welcome center. These roofs' intersecting planes and their contrast to the curvilinear stairs that Gehry has designed for the buildings give the campus a fractious excitement common to his work on any scale. History, interrupted

Gowdy says she hopes to have two or three of the buildings open by the fall of 2009, but a volatile construction market could delay it further. Crain (who called his work on the Ohr Museum “the most rewarding experience of my professional career") and his firm are working on a maritime museum next door to the Ohr museum. There’s also a historic pier for early 20th century ships nearby, and all this, he says, could shape the beginnings of a museum district. With a Gehry project already starting its dance with the trees, the Biloxi Gulf Coast is set to take center stage. |

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design