Vietnam Veterans Memorial Receives

Twenty-five

Year Award

by Russell Boniface

Associate Editor

Summary: Maya

Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., as nominated

by the AIA Committee on Design, will receive the 2007 Twenty-five

Year Award, honoring structures of enduring significance completed

25 to 35 years ago. Officially opened to the public in 1982, the

Vietnam Veterans Memorial is Lin’s most recognized structure. The AIA campaigned successfully to support construction of Lin’s powerfully evocative yet elegantly simple design and, in 1984, awarded the project an AIA Honor Award for Architecture. Summary: Maya

Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., as nominated

by the AIA Committee on Design, will receive the 2007 Twenty-five

Year Award, honoring structures of enduring significance completed

25 to 35 years ago. Officially opened to the public in 1982, the

Vietnam Veterans Memorial is Lin’s most recognized structure. The AIA campaigned successfully to support construction of Lin’s powerfully evocative yet elegantly simple design and, in 1984, awarded the project an AIA Honor Award for Architecture.

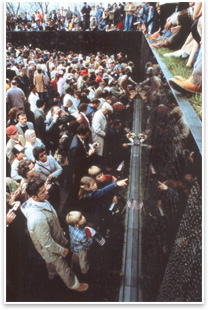

The two-acre Vietnam Veterans Memorial is on the grassy National Mall in Washington D.C., just northeast of the Lincoln Memorial. Prior to its dedication on November 14, 1982, the concept of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial generated heated national interest. In 1981, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, the group that spearheaded the project, held a public design competition that garnered 1,421 entries—the largest design competition in our nation’s history. The submissions filled a hangar stretching over one mile. After two rounds of elimination, Lin’s design was chosen. The two-acre Vietnam Veterans Memorial is on the grassy National Mall in Washington D.C., just northeast of the Lincoln Memorial. Prior to its dedication on November 14, 1982, the concept of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial generated heated national interest. In 1981, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, the group that spearheaded the project, held a public design competition that garnered 1,421 entries—the largest design competition in our nation’s history. The submissions filled a hangar stretching over one mile. After two rounds of elimination, Lin’s design was chosen.

An architecture student awes us all

Only 21 and an undergraduate at Yale, Lin required an architect of record to realize the design, so she sought the advice of Cesar Pelli, then the dean of Yale’s School of Architecture. He suggested Cooper-Lecky Architects, a firm in Washington, D.C., which was ultimately selected.

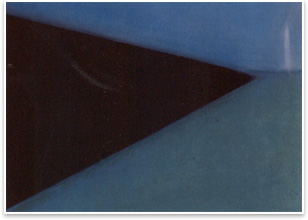

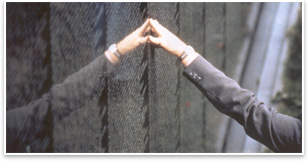

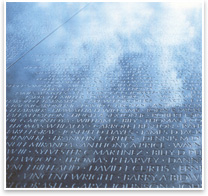

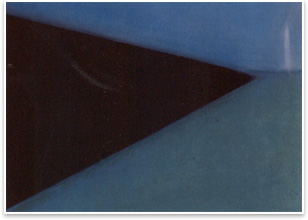

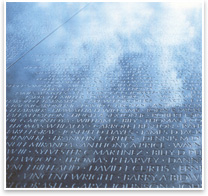

The monument’s most recognized feature is its black-granite, V-shaped Memorial Wall, with its west arm pointing to the Lincoln Memorial and its east extension reaching toward the Washington Monument. The concrete retaining walls that support the granite panels are each 246 feet long. Inscribed on the wall are the names of 58,000 men and women who either died or remained classified as missing in action when the wall was constructed. The names are listed in killed-in-action chronological order. The monument’s most recognized feature is its black-granite, V-shaped Memorial Wall, with its west arm pointing to the Lincoln Memorial and its east extension reaching toward the Washington Monument. The concrete retaining walls that support the granite panels are each 246 feet long. Inscribed on the wall are the names of 58,000 men and women who either died or remained classified as missing in action when the wall was constructed. The names are listed in killed-in-action chronological order.

The jury in 1981 selected Lin’s design because “it clearly

met the spirit and formal requirements of the program . . . its open

nature would encourage access on all occasions, at all hours, without

barriers and yet free the visitors from the noise and traffic of

the surrounding city.”

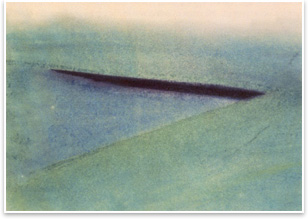

At the center of her competition boards, Lin wrote: “Walking through this park-like area the memorial appears as a rift in the earth—a long, polished black stone wall, emerging from and receding into the earth. Walking into the grassy site contained by the walls of this memorial we can barely make out the carved names upon the memorial’s walls. These names, seemingly infinite in number, convey the sense of overwhelming numbers, while unifying those individuals into a whole. For this memorial is meant not as a monument to the individual, but rather as a memorial to the men and women who died during the war, as a whole.” At the center of her competition boards, Lin wrote: “Walking through this park-like area the memorial appears as a rift in the earth—a long, polished black stone wall, emerging from and receding into the earth. Walking into the grassy site contained by the walls of this memorial we can barely make out the carved names upon the memorial’s walls. These names, seemingly infinite in number, convey the sense of overwhelming numbers, while unifying those individuals into a whole. For this memorial is meant not as a monument to the individual, but rather as a memorial to the men and women who died during the war, as a whole.”

Names etched in granite send a timeless message

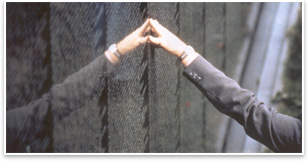

Lin wanted an almost pure black, highly reflective, granite surface to serve as the “pages” for this book of names. Boulders quarried in India were fabricated in Vermont, where the stone was carefully measured, sliced, cut, edged, and polished. No two panels were the same size and shape. It was in Memphis during the blasting of the names where Lin’s design began to emerge, as the rich polish of the black granite panels acted like a mirror, suddenly throwing the names across the reflected face of the viewer, who becomes one with the names.

“The Memorial is a message to all visitors about the horrendous loss of war, the tragic cost of conflict,” wrote Louis R. Pounders, FAIA, chairman, Twenty-five Year Award Committee, in his nomination letter. “It is a message that is timeless.” “The Memorial is a message to all visitors about the horrendous loss of war, the tragic cost of conflict,” wrote Louis R. Pounders, FAIA, chairman, Twenty-five Year Award Committee, in his nomination letter. “It is a message that is timeless.”

In Lin’s own description, “The black granite walls effectively

act as a sound barrier, yet are of such a height and length so as

not to appear threatening or enclosing. The actual area is wide and

shallow; allowing for a sense of privacy.”

As a National Memorial,

it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places the same

day it was dedicated. In 1984, the memorial was recognized with the

National AIA Honor Award for Architecture.

A clear vision

Maya Lin, born in Athens, Ohio, is a principal of Maya Lin Studios

in New York City. Continuing as a noted memorial designer, her

best-loved works include the Civil Rights Memorial, Montgomery

(1989), and the Wave Field, at the University of Michigan (1995).

In 1994, she was the subject of the Academy Award-winning documentary

Maya Lin: A Strong Clear Vision. The title comes from an address

she gave at Yale, in which she speaks of the monument design process.

In

2000, Lin agreed to act as the artist and designer for the Confluence

Project, a series of outdoor installations at historical points along

the Columbia River and Snake River in the state of Washington—the

largest and longest project she has undertaken. In 2003, Lin served

on the selection jury of the World Trade Center Site Memorial Competition.

In 2005, she was elected to The American Academy of Arts and Letters

and the National Women's Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls, N.Y. In

2000, Lin agreed to act as the artist and designer for the Confluence

Project, a series of outdoor installations at historical points along

the Columbia River and Snake River in the state of Washington—the

largest and longest project she has undertaken. In 2003, Lin served

on the selection jury of the World Trade Center Site Memorial Competition.

In 2005, she was elected to The American Academy of Arts and Letters

and the National Women's Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls, N.Y.

|

Summary:

Summary: The two-acre Vietnam Veterans Memorial is on the grassy National Mall in Washington D.C., just northeast of the Lincoln Memorial. Prior to its dedication on November 14, 1982, the concept of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial generated heated national interest. In 1981, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, the group that spearheaded the project, held a public design competition that garnered 1,421 entries—the largest design competition in our nation’s history. The submissions filled a hangar stretching over one mile. After two rounds of elimination, Lin’s design was chosen.

The two-acre Vietnam Veterans Memorial is on the grassy National Mall in Washington D.C., just northeast of the Lincoln Memorial. Prior to its dedication on November 14, 1982, the concept of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial generated heated national interest. In 1981, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, the group that spearheaded the project, held a public design competition that garnered 1,421 entries—the largest design competition in our nation’s history. The submissions filled a hangar stretching over one mile. After two rounds of elimination, Lin’s design was chosen. The monument’s most recognized feature is its black-granite, V-shaped Memorial Wall, with its west arm pointing to the Lincoln Memorial and its east extension reaching toward the Washington Monument. The concrete retaining walls that support the granite panels are each 246 feet long. Inscribed on the wall are the names of 58,000 men and women who either died or remained classified as missing in action when the wall was constructed. The names are listed in killed-in-action chronological order.

The monument’s most recognized feature is its black-granite, V-shaped Memorial Wall, with its west arm pointing to the Lincoln Memorial and its east extension reaching toward the Washington Monument. The concrete retaining walls that support the granite panels are each 246 feet long. Inscribed on the wall are the names of 58,000 men and women who either died or remained classified as missing in action when the wall was constructed. The names are listed in killed-in-action chronological order. At the center of her competition boards, Lin wrote: “Walking through this park-like area the memorial appears as a rift in the earth—a long, polished black stone wall, emerging from and receding into the earth. Walking into the grassy site contained by the walls of this memorial we can barely make out the carved names upon the memorial’s walls. These names, seemingly infinite in number, convey the sense of overwhelming numbers, while unifying those individuals into a whole. For this memorial is meant not as a monument to the individual, but rather as a memorial to the men and women who died during the war, as a whole.”

At the center of her competition boards, Lin wrote: “Walking through this park-like area the memorial appears as a rift in the earth—a long, polished black stone wall, emerging from and receding into the earth. Walking into the grassy site contained by the walls of this memorial we can barely make out the carved names upon the memorial’s walls. These names, seemingly infinite in number, convey the sense of overwhelming numbers, while unifying those individuals into a whole. For this memorial is meant not as a monument to the individual, but rather as a memorial to the men and women who died during the war, as a whole.” “The Memorial is a message to all visitors about the horrendous loss of war, the tragic cost of conflict,” wrote Louis R. Pounders, FAIA, chairman, Twenty-five Year Award Committee, in his nomination letter. “It is a message that is timeless.”

“The Memorial is a message to all visitors about the horrendous loss of war, the tragic cost of conflict,” wrote Louis R. Pounders, FAIA, chairman, Twenty-five Year Award Committee, in his nomination letter. “It is a message that is timeless.” In

2000, Lin agreed to act as the artist and designer for the Confluence

Project, a series of outdoor installations at historical points along

the Columbia River and Snake River in the state of Washington—the

largest and longest project she has undertaken. In 2003, Lin served

on the selection jury of the World Trade Center Site Memorial Competition.

In 2005, she was elected to The American Academy of Arts and Letters

and the National Women's Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls, N.Y.

In

2000, Lin agreed to act as the artist and designer for the Confluence

Project, a series of outdoor installations at historical points along

the Columbia River and Snake River in the state of Washington—the

largest and longest project she has undertaken. In 2003, Lin served

on the selection jury of the World Trade Center Site Memorial Competition.

In 2005, she was elected to The American Academy of Arts and Letters

and the National Women's Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls, N.Y.