|

Summary: The AIA Board of Directors voted on December 7 to award posthumously the 2007 AIA Gold Medal to Edward Larrabee Barnes, FAIA. Barnes is remembered for fusing Modernism with vernacular architecture and understated design. The AIA Gold Medal, awarded annually, is the highest honor the AIA confers on an architect. The Gold Medal honors an individual whose significant body of work has had a lasting influence on the theory and practice of architecture. Barnes will be commemorated at the American Architectural Foundation Accent on Architecture Gala, February 9, 2007, at the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C.

“This would mean a tremendous amount to my father. Thank you very much,” said John Barnes when AIA President Kate Schwennsen, FAIA, called to tell him about the Board’s selection. “I can’t thank you enough.” Modest, geometric signature

In supporting Barnes for the award, Toshiko Mori, FAIA, chair, Department of Architecture, Harvard Graduate School of Design, pointed out, “Barnes’ work is held in high regard among architects internationally and is influential in reassessing both the contemporary and future models of architecture. It has a generous sense of proportion spatially which is very different from precedent European models ... imbued with his social and spiritual understanding of the cultural aspects of the program and his sympathetic and humanistic attitude as an architect.”

Bruce Fowle, FAIA, who was an employee and associate of Barnes for eight years, attached a list of 136 colleagues and collaborators who endorsed Barnes’ for the Gold. Fowle described the Barnes’ work environment as the best that he ever experienced. “Both Ed and his wife Mary, who collaborated on many of his projects, were gracious and generous people. They treated all their employees with dignity and made everyone—and their families—feel that they were important contributors to the firm … Everyone in the office awaited the famous kitchen table sketches. He was remarkable in his ability to ‘read’ a complex program of requirements and turn it into a wonderfully simple architectural idea.”

Barnes’ national awards include:

Barnes becomes the 63rd AIA Gold Medallist, joining the ranks of such visionaries as Thomas Jefferson (1993), Frank Lloyd Wright (1949), Louis Sullivan (1944), LeCorbusier (1961), Louis Kahn (1971), I.M. Pei (1979), Cesar Pelli (1995), Santiago Calatrava (2005), and last year’s recipient, Antoine Predock. Barnes was 89 when he died in 2004. In recognition of his legacy to architecture, his name will be chiseled into the granite Wall of Honor in the lobby of the AIA headquarters in Washington, D.C.

|

||

Copyright 2006 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

Celebration of the awarding of the 2007 AIA Gold Medal to Edward Larrabee Barnes and the 2007 AIA Firm Award to Leers Weinzapfel will take place at the annual Accent on Architecture celebration on February 9 at the National Building Museum, Washington, D.C. The AIA Board of Directors noted how fitting it is that these awards be made during the AIA150 sesquicentennial celebration year, the slogan for which is “Celebrating the Past—Designing the Future.” Barnes through his architectural legacy represents the firm foundation of our past, while the young firm of Leers Weinzapfel represents our faith in a future of excellence.

Celebration of the awarding of the 2007 AIA Gold Medal to Edward Larrabee Barnes and the 2007 AIA Firm Award to Leers Weinzapfel will take place at the annual Accent on Architecture celebration on February 9 at the National Building Museum, Washington, D.C. The AIA Board of Directors noted how fitting it is that these awards be made during the AIA150 sesquicentennial celebration year, the slogan for which is “Celebrating the Past—Designing the Future.” Barnes through his architectural legacy represents the firm foundation of our past, while the young firm of Leers Weinzapfel represents our faith in a future of excellence.

Photo Captions:

1. 2007 Gold Medal Recipient Edward Larrabee Barnes. Photo © Nancy Rica Schiff.

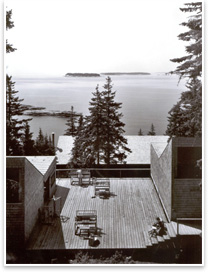

2. Haystack Mountain School of Arts and Crafts, Deer Isle, Maine. The project captured the 1993 AIA Twenty-Five Award. Photo © Joseph Molitor.

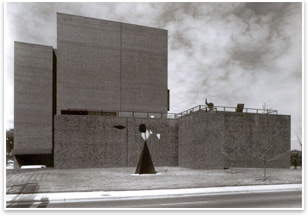

3. Barnes’ Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, has been described as the perfect foil for contemporary Modern Art. Photo © Joseph Cserna.

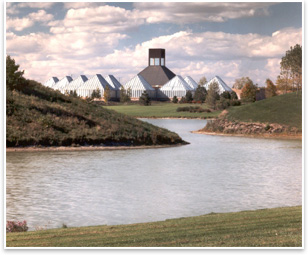

4. The Chicago Botanic Garden illustrates Barnes’ elemental skill at blending built and natural environment. Photo © Nick Wheeler.

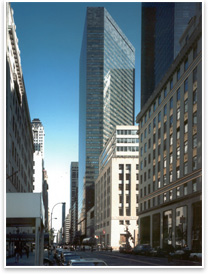

5. IBM 590 Madison Avenue, New York City, shelters a much used and loved public plaza within its neatly detailed and elegantly proportioned walls. Photo © Cervin Robinson.

Edward Larrabee Barnes, FAIA, Selected for 2007 AIA Gold Medal

Edward Larrabee Barnes, FAIA, Selected for 2007 AIA Gold Medal