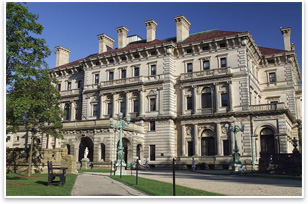

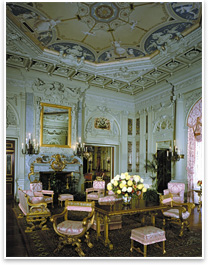

| Turning Over an Old Leaf Rare platinum coating discovered in the historic Breakers mansion Summary: The Preservation Society of Newport County in Rhode Island has discovered rare platinum leaf decorating wall surfaces and ceiling panels at the historic Breakers mansion, a 70-room, 138,000-square-foot Italian Renaissance-style palazzo completed in Newport in 1895 by the prominent Vanderbilt family. Using non-invasive, state-of-the-art conservation techniques, the Preservation Society worked with the Delaware-based Winterthur Museum to uncover why the 100-year-old, silver-colored surfaces—thought to be decorated with silver, aluminum, or tin leaf—hadn’t tarnished in more than a century. Their analysis confirmed that the leaf’s silver appearance belied its true identity: platinum.

Moore explains that platinum leaf in 19th-century architecture had to have been rare due to its expense and the difficulty to find it, pointing out that there is almost no documentation of its use in architecture during the Gilded Age. He cites only one research find: the Euclid Avenue Opera House in Cleveland, an opulent 19th century structure that used both gold and platinum leaf. “Otherwise, restorers, architects, and conservators didn’t know about it.”

Platinum is known for its durability and resistance to tarnishing, says Moore. “It’s an inert, noble metal, like gold, so it is resistant to everything that you can throw at it. Its natural state is not to oxidize and it is less malleable than gold.” Its high melting point (lowered by mixing with arsenic) makes platinum working very dangerous, and only undertaken by crafters such as Fabergé in producing Easter eggs for the Russian czars. Today, it is most widely used, in microscopic layers, in car catalytic converters because it burns off emissions at very high temperatures.

The next step, Moore explains, was to analyze if the leaf gilding the wall surface was consistent with the ceiling panels. This past summer, Moore collaborated with the Winterthur Museum assistant scientist Catherine Matsen and Natasha Loblo, a Winterthur Conservation Program fellow and preservation intern. Loblo aimed a handheld fluorescent X-ray machine to non-destructively test the walls, and, together, they discovered platinum leaf in the eight wall panels. “The device had a Star Wars name and looked like a blue plastic ray gun,” jokes Moore. “Natasha hooked it up to a laptop, and it told us the metals and inorganics of the leaf at which it was pointed. The very discovery of platinum leaf gilding the surface expanse was pretty amazing.” There must be more platinum |

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› “Latrobe’s Baltimore Basilica to Celebrate 200th Birthday”

› “Historic Preservation and Architecture Education: A Dialogue”

› “Buffalo Spreads Its Restoration Wings”