4/2006

Event marks restoration of America’s masterful first cathedral

by Tracy Ostroff

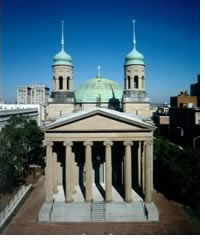

Benjamin

Henry Latrobe’s Baltimore Basilica will celebrate its

grand reopening this November with $32 million in donations for a birthday

present to mark its 200th anniversary. The funds are paying for a top-to-bottom

restoration of Latrobe’s masterpiece, from its original domes and

skylights to establishing access to the undercroft, site of masterful

architectural and engineering elements. Historic preservation architect

John G. Waite Associates, Albany, N.Y., with contractor Henry H. Lewis,

Baltimore, are conducting the restoration, which is revealing the basilica’s

layers of significance as a major symbol of the Catholic Church.

Benjamin

Henry Latrobe’s Baltimore Basilica will celebrate its

grand reopening this November with $32 million in donations for a birthday

present to mark its 200th anniversary. The funds are paying for a top-to-bottom

restoration of Latrobe’s masterpiece, from its original domes and

skylights to establishing access to the undercroft, site of masterful

architectural and engineering elements. Historic preservation architect

John G. Waite Associates, Albany, N.Y., with contractor Henry H. Lewis,

Baltimore, are conducting the restoration, which is revealing the basilica’s

layers of significance as a major symbol of the Catholic Church.

The basilica was born of a partnership of Latrobe and Archbishop of Baltimore John Carroll. “Everyone has always heard that it’s one of Latrobe’s greatest—if not his greatest—architectural works, so when we had the opportunity to work on the restoration we were very pleased,” Waite says. “We learned how really significant the building was, and not only for architectural reasons. It illustrates very graphically not only Latrobe’s genius, but also the collaboration of Thomas Jefferson and also the really strong influence of Archbishop John Carroll.”

The cornerstone of what was called the Baltimore Cathedral was laid

in 1806. The restoration addresses key elements of Latrobe’s original

design, including the windows, balconies, sanctuary, and interior finishes,

which had been altered in many en vogue fashions during its history.

Now, to step into the basilica is to see how Latrobe designed it 200

years ago. The restoration team also upgraded the mechanical, electrical,

and plumbing infrastructure to make it compliant with the Americans with

Disabilities Act.

The cornerstone of what was called the Baltimore Cathedral was laid

in 1806. The restoration addresses key elements of Latrobe’s original

design, including the windows, balconies, sanctuary, and interior finishes,

which had been altered in many en vogue fashions during its history.

Now, to step into the basilica is to see how Latrobe designed it 200

years ago. The restoration team also upgraded the mechanical, electrical,

and plumbing infrastructure to make it compliant with the Americans with

Disabilities Act.

The basilica, officially known as the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, was the first metropolitan cathedral and major religious building constructed in America after the adoption of the Constitution. Now a National Historic Landmark and National Shrine, the church would help shape the direction of Catholic Church in America. It is the site of the country’s first Catholic archdiocese, later became the home of the first order of African-American nuns, and witnessed the consecration of many of America’s first Catholic bishops and a series of councils that guided the rapid growth of Catholicism in the 19th century.

Restoration uncovers connections of genius

Restoration uncovers connections of genius

“Latrobe was not a Catholic. His family included a long line of Moravian

bishops. Archbishop Carroll sought him out even though there were a number

of very good Catholic architects in Baltimore,” Waite explains. “Archbishop

Carroll realized that Latrobe was the best architect in the country. If

the Catholic Church was going to be more than a persecuted minority—which

it had been only 20 years before the basilica was started—if it really

was going to grow with the new nation, it needed a major architectural

symbol,” he

says.

Latrobe obliged and created a design for a Gothic Revival building, the drawings for which are still in the archbishop’s house in Baltimore. But Carroll had other thoughts. “Carroll realized that if he built a Gothic-style building that anti-Catholic forces would use it against the church,” Waite explains. The archbishop really wanted a modern building for its time, which meant the Neoclassical style. “He wanted something on the scale and sophistication of Latrobe’s U.S. Capitol,” Waite says. Carroll persuaded Latrobe to build the present Neoclassical building. After seven design schemes, which also remain in the archbishop’s house today, he went on to create the masterpiece consecrated in 1821.

“The Basilica ranks as one of the great buildings in Western architecture,” says Charles Brownell, professor of art history at Virginia Commonwealth University in a description of the restoration project. “At the Baltimore Basilica, it is a newly visible and much more brilliant Latrobe whom we encounter and a newly knowable and much more precious edifice we have in our care.”

Jefferson’s influence

Jefferson’s influence

Waite describes the close relationship the architect enjoyed with President

Thomas Jefferson during the cathedral’s construction. “In

1805, when Latrobe was designing domes for the Senate and House of

Representatives chambers in the Capitol, he and Jefferson were very

close and communicating about construction techniques and architectural

design.”

Detailed correspondence between the two gentlemen reveals they didn’t always see eye-to-eye, Waite says. Latrobe insisted on masonry domes for the U.S. Capitol building, making the case that a major public building had to have the architecture that would denote its significance. “He tells Jefferson that the only proper way of providing illumination in the dome is by having a lantern on top, which he did in his Bank of Pennsylvania in 1800.” Instead, Waite says, Jefferson wanted a wooden dome, a technique he used for the dome at Monticello and later for the Rotunda at the University of Virginia. Latrobe resisted, but “Jefferson had the last word, and instructs him to put skylights in the dome. Latrobe tells him the skylights are going to create glare and that they are going leak. Jefferson told him to do it anyway. Guess what? Latrobe was absolutely right.”

Waite

explains that Jefferson was one of the few people Latrobe had respect

for as an amateur architect and someone interested in building. “Twelve

years later, when he’s doing the dome on the basilica, he takes

Jefferson’s idea of using a wood frame dome and putting skylights

in those domes. He does exactly what he said he would never do, and that

nobody should do, 12 years earlier. But he’s learned that there’s

some real merit in this, and meanwhile he’s talked with Jefferson

back-and-forth. To control the glare and the leaking problem, he puts

an inner dome of masonry in the space and directs all light through

an oculus that is focused down on the altar. It’s really a work

of genius.”

Waite

explains that Jefferson was one of the few people Latrobe had respect

for as an amateur architect and someone interested in building. “Twelve

years later, when he’s doing the dome on the basilica, he takes

Jefferson’s idea of using a wood frame dome and putting skylights

in those domes. He does exactly what he said he would never do, and that

nobody should do, 12 years earlier. But he’s learned that there’s

some real merit in this, and meanwhile he’s talked with Jefferson

back-and-forth. To control the glare and the leaking problem, he puts

an inner dome of masonry in the space and directs all light through

an oculus that is focused down on the altar. It’s really a work

of genius.”

The interactions and connections continue through the time Jefferson designs the University of Virginia, so much so the theory now is that Latrobe had a hand in doing some of the buildings at UVA. “Latrobe and Jefferson worked very closely together, and a lot of the things in the basilica are what Latrobe would have done in the Capitol had he not inherited a building that William Thornton started, and he had to work with the carcass of that initial design,” Waite says.

Restoring Latrobe’s vision

The team received a Getty Grant to investigate the dome. What they found

was all the evidence for Latrobe’s original 24 skylights and

how it was originally constructed. They also found the “existing

roof was built up quite high against the base of the dome and that

the whole base was meant to be seen and not be cut off by the roof,” Waite

says. They also encountered a completely encapsulated wood shingle

roof, which had been covered over from the time of the Civil War. “The

Architect of the Capitol’s office confirmed that wood shingle

was Latrobe’s material of choice for that building as well—but

the British burned the wood shingle roofs on the Capitol in 1815,”

Waite explains.

The

architects were able to restore the dome and skylight as they had been

constructed by Latrobe, in part by using paint schemes. “It’s

like night and day—the difference between Latrobes’ design

and what we started with, which was basically 1940s and ’50s

renovations with the usual trappings of a parish church of the period,

including stained glass and dark painted finishes.

The

architects were able to restore the dome and skylight as they had been

constructed by Latrobe, in part by using paint schemes. “It’s

like night and day—the difference between Latrobes’ design

and what we started with, which was basically 1940s and ’50s

renovations with the usual trappings of a parish church of the period,

including stained glass and dark painted finishes.

“We had Latrobe’s seventh design in a cross-section watercolor that he did. It showed that in the base of the dome there were four panels for murals of the four evangelists. We did soundings around the dome and we found a hollow area, behind which was one of these panels—completely intact,” Waite says. They had the same experience in the other three locations. Now exposed, cleaned, and restored, the murals’ colors match perfectly with the restored colors, reinforcing that the analysis had really uncovered the original colors accurately, Waite says.

Engineering masterpiece

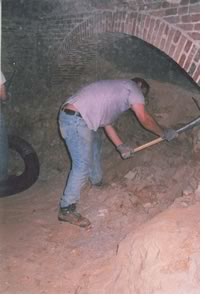

“It’s not only important historically and architecturally,

it’s also Latrobe’s greatest engineering work,” Waite

says.

It wasn’t always easy-going for the architect-engineer. Waite

notes that Latrobe resigned twice: once because the contractor misread

his drawings and started building the foundations upside down, and the

other time because the clerk of the works thought he had better ideas

than Latrobe. His problem, Waite explains, is that Latrobe scientifically

laid out the foundation so that there were modular brick blocks for the

vaults in the undercroft. “He wanted the bricks to all be a certain

dimension. Well, the contractor didn’t pay attention to that and

didn’t make the bricks modular,” Waite explains. “Also,

the clerk of the works and the contractor couldn’t imagine that

you would have a vaulted ceiling when a wood beam ceiling would be just

fine. Latrobe got really annoyed with that, and they had to put the vaults

there.”

It wasn’t always easy-going for the architect-engineer. Waite

notes that Latrobe resigned twice: once because the contractor misread

his drawings and started building the foundations upside down, and the

other time because the clerk of the works thought he had better ideas

than Latrobe. His problem, Waite explains, is that Latrobe scientifically

laid out the foundation so that there were modular brick blocks for the

vaults in the undercroft. “He wanted the bricks to all be a certain

dimension. Well, the contractor didn’t pay attention to that and

didn’t make the bricks modular,” Waite explains. “Also,

the clerk of the works and the contractor couldn’t imagine that

you would have a vaulted ceiling when a wood beam ceiling would be just

fine. Latrobe got really annoyed with that, and they had to put the vaults

there.”

The vaults, Waite says, are really a good indication of Latrobe’s deft engineering ability. “To support the huge mass of the main dome, the rotunda area, he takes and has inverted arches going into the ground so that you have these arches that are actually carrying the weight of the pendentives of the rotunda. The arch distributes those loads evenly on the soil. It’s just a really brilliant solution.” Studies reveal the dome and inverted arches have stood the test of time. “We used really state-of-the-art non-destructive investigation techniques to find out what the condition of that masonry was,” Waite says. “It was really a work of genius to use those inverted arches to carry the dome weight, because there are no cracks, no structural disturbances in that area at all.”

The arches will be exposed along with a chapel in the undercroft. “One of the problems with the contractor reading the drawings upside down and constructing the buildings to the wrong dimensions was that there wasn’t enough headroom. We excavated down and underpinned all those brick walls, so that we do have the space for the chapel in the undercroft. That chapel is defined completely by Latrobe’s original brick-vaulted arch architecture. Since it was never done historically, we treated it in a very contemporary way as far as furnishings and fittings,” Waite concludes.

Copyright 2006 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

The basilica’s grand reopening celebration takes place November, 4. A week of tours, open houses, special events, and other festivities will follow, culminating with a procession of America’s Catholic bishops into the basilica for a special celebratory service on November 12.

Photographs are property of the Basilica of the Assumption Historic Trust, Inc., unless otherwise noted.

![]()