diversity

Minority Architects Rebuild Pittsburgh from

the Grassroots Up

by Zach Mortice

Associate Editor

Summary: Carnegie

Mellon’s “UDream” program helps minority students

understand a troubled community--and then gives them a chance to

fix it.

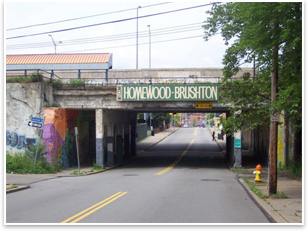

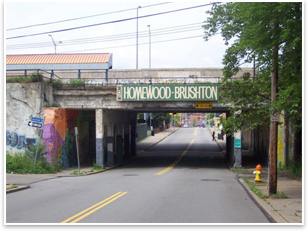

The Homewood-Brushton neighborhood of Pittsburgh.

Photo courtesy of the Carnegie Mellon School of Architecture Remaking

Cities Institute.

If the colligate academy of architecture is criticized as a designer-centered

ivory tower separate from the true-to-life state of cities and urbanism,

consider the Carnegie Mellon

School of Architecture’s Urban

Design Regional Employment Action for Minorities (UDream) program

as a rejoinder. This opportunity, run by Carnegie Mellon’s

Remaking Cities Institute, gets minority

architects working with minority communities at a grassroots level

with projects that engage the public in bringing their neighborhoods

back to life.

The Remaking Cities Institute is an urban think tank

and research center focused on urban planning. With strong relationships

with local non-profits, the institute promotes the natural evolution

of eclectic and fine-grained urbanism. In conjunction with the institute,

the UDream program has three simple goals: to increase minority participation

in architecture and urban planning, to potentially retain these talents

in Pittsburgh, and to search for urban interventions that could aid

the struggling and declining Homewood-Brushton neighborhood on Pittsburgh’s

east side.

Studying the city

UDream and the Remaking Cities Institute sponsored seven African-American

recent architecture school graduates’ participation. The program

began on June 1 and finished on Sept. 5, and was divided into two

primary components. The first four weeks were spent taking classes

at Carnegie Mellon and studying the Homewood-Brushton neighborhood.

In the classroom, the students studied sustainable design, digital

fabrication, and urban planning.

Outside of the classroom, they took

walking and boat tours of the city, familiarizing themselves with

the urbanism they would be designing in. (They also got in a trip

to Fallingwater, Frank Lloyd Wright’s

masterpiece.) At the end of this period they also worked on specific

design suggestions for Homewood-Brushton. The remainder of the summer

was spent at internships with local architecture firms and community

development non-profits. (True to UDream’s goal’s, one

firm even hired their intern full-time).

Ken Doyno, AIA, of Rothschild

Doyno Collaborative in Pittsburgh, hosted two UDream interns at his

firm. One worked on a housing project on a sloped site in the Hill

District neighborhood. The other worked with a local human services

non-profit, called the Hosanna House, on finding ways to link it

to the surrounding community. “Success

right now in the [Hosanna House] program has meant leaving the community,

so the goal was to try to develop a vision of how to have success

in the Hosanna House connect to the surrounding properties,” Doyno

says.

Past and future

The structure and content of the UDream program makes it clear that

its mission is to train architects as design-savvy community activists,

not sculptural technicians. Much of the students’ work centered

on tapping the local community’s expertise and refining it

into urban solutions. Don Carter, FAIA, director of the Remaking

Cities Institute, asks that, above all, students show respect for

existing urban contexts and cultures, facilitate the community’s

participation, and listen. “Learn from the community,” he

added, “because they’re the experts. They know what their

neighborhoods are about.”

“We often talk about what makes a piece of architecture rich,” says

Derric Heck, a UDream student. “I think one of the things that

makes it rich is when it’s representative of the people it

is intended to serve. I would like for architecture schools to emphasize

the personable nature of architecture. Of course you want people

to be technically proficient, but if that thing [you’re designing]

does not represent the people it’s going to serve, it’s

really for naught.”

In many ways, Homewood-Brushton is suffering

from a sadly typically litany of post-industrial Rust Belt urban

problems: declining populations and commercial corridors, endemic

poverty, poor municipal infrastructure, a lack of proper housing,

and blighted and abandoned lots.

The neighborhood was originally

settled in the 1880s, and was the home of ethnic white minorities

(Germans, Italians, Jews), as well as some African-Americans, making

the area one of the most diverse and integrated parts of the city.

In 1951, the Pittsburgh Redevelopment Authority revealed a plan rebuild

vast stretches of the Lower Hill District neighborhood, another African-American

area, clearing out 95 acres in total. These people were largely resettled

into Homewood-Brushton, confined to this and other adjacent neighborhood

by unfair lending practices and residential redlining.

“Fifty years later, people still feel the pain of [that relocation],” says

Heck, an architecture graduate from Florida A&M University. Many

middle class white families fled the neighborhood for suburban areas

when their new neighbors started moving in. The neighborhood further

suffered from the riots caused by the assassination of Martin Luther

King, Jr. in 1968, and the crack cocaine epidemic of the 1980s.

To

deal with these problems and legacy of urban disinvestment, the UDream

students focused on the social and economic fabric of the neighborhood

as well as its built fabric. The students looked for ways to capitalize

on the area’s existing architectural and

cultural strengths. Though dilapidated, the housing stock there is

well-built, and ripe for gentrifying investment. The neighborhood

contained the nation’s first ever African-American opera house,

the National Opera House, and it’s still home to a long-standing

African-American music community center.

The students also looked

for ways to connect Homewood-Brushton to the bus mass transit system

in the city. They also examined ways to reinvigorate the area’s

commercial core, affordable housing, and establish business incubators

and urban farms. (Like many poor neighborhoods, the nearest grocery

store is miles away.) To begin with, the UDream students wanted to

help instill a positive self-image for the neighborhood with simple,

small improvements: murals, better street lighting, new sidewalks

and pavers, landscaping, and pedestrian bridges.

Carter says the program’s focus on diversity was key in assuring

vital neighborhood buy-in. “If you’re working in minority

neighborhoods, having facilitators who are of that group in the room

makes it a lot easier to get to the point of trusting the process,” he

says. “You need people that are familiar with the culture and

can understand where the community is coming from. It’s not

that every other professional can’t work that way and do the

work. In fact, that’s the way it’s gone for the most

part. It does add to the richness of the process to have that mosaic

of people.”

If architecture and urban planning had been more

diverse and inclusive when these heavy-handed urban redevelopment

decisions that have scarred neighborhoods and caused this lack of

trust between people and planners were made, they would likely have

been avoided, Carter says. The problem, he says, lied both in the

lack of diversity and community perspective around design and planning

studio tables, as well as with the decision making process itself,

which was purely top-down, with little call (or tolerance) for public

participation.

“Community organizer”

During the summer internship portion of the UDream program, Heck

found himself working to put a new face on the Pittsburgh Redevelopment

Authority for the Homewood-Brushton community decades after the agency

irreparably changed their neighborhood and relationship to the city.

Heck succinctly describes his role with the redevelopment agency

as a “community organizer.” He was responsible for putting

together a neighborhood steering committee that would select architects

for Homewood-Brushton projects. His primary goal was to identify

people to sit on the committee, but he also worked on programming,

development, and research projects—essentially training people

to become stakeholders and advocates for their own neighborhoods.

Along the way, Heck discovered that design solutions reside just

as often with the people architects serve as they do with designers’ own

skills. “Working with this group of individuals just showed

that research can come from technical experts, and it can come from

children,” he says.

“The community was very open and accepting of [the UDream students,]” Carter

says, “and very proud of them, because the community didn’t

normally see seven African-American architects coming in to work

in a neighborhood.” |