| Citizens Schools Diversifying Architecture from the Bottom Up

by Layla Bellows

How do you . . . work with underserved and low-income middle school students to introduce them to the profession and invest in diversifying architecture’s future?

Summary: As the profession increasingly recognizes its need to become more diverse, practitioners in the Boston area are working to create long-term change through their involvement with Citizen Schools, a program that provides increased educational opportunities to middle-school students in underserved areas.

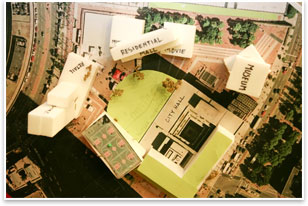

Close-up of a Citizen Schools building model students created with the guidance of the volunteers from Jones Lang LaSalle. Image courtesy of Citizen Schools.

Ted Landsmark, Assoc. AIA, president of the Boston Architectural College, will never forget the day he saw a woman present the case for adding public restrooms to what was a newly created greenway in downtown Boston. She was young and homeless; the room was full of Boston’s civic leaders, public officials, and heads of corporations. She explained that young people in her situation can’t just go into a restaurant or department store to use their bathroom. The experience is uncomfortable, and, as a result, many her age wouldn’t head to the downtown area.

“It was the simplest thing,” he says, “yet as professional designers, it’s not the kind of thing we teach in school or think about with most of our clients because most of our clients are not young, homeless women.”

To many, that idea could seem obvious. However, as architects shape a city, it seems equally obvious that the end-users, the ultimate clients, are those who experience the city on the ground level. Developing a vibrant, livable city takes multiple viewpoints, backgrounds and life experiences, and this is something not just lacking as ideas are developed. It’s something that can be missing from architecture as a whole.

“I know that the practitioners in firms who have had opportunities to work with young people from communities have always learned something new,” Landsmark says.

The girl’s presentation was the culmination of a semester spent studying design and architecture at Citizen Schools’ 10-week-long after-school apprenticeships. Offered to middle school students in underserved communities, these sessions are led by professionals in a variety of fields who work closely with a Citizen Schools staff member. Taking on the job of keeping the attention of 15 or so 12-year-olds can be a daunting job and the program thoroughly trains and supports the practitioners who take part in the program.

Professional help

Gretchen Schneider, Assoc. AIA, of the Boston firm Schneider Studio, was teaching a Citizen Schools class that focused on Boston City Hall and City Hall Plaza. One of her transformative moments came when the kids asked: “Why should we care about city hall or City Hall Plaza when our neighborhoods look the way they do?”

It left Schneider speechless—and why not? For most people, it seems obvious that a city hall should use powerful, emotive design to express democracy. But the contrast between the attention heaped on a celebrated or reviled civic building and the neglect through disinvestment of many impoverished neighborhoods makes it clear to any resident of such a place that architects’ skills are not always evenly applied. A parent came to the rescue and explained what many of us take as a matter of course.

Close-up of a Citizen Schools building model students created with the guidance of the volunteers from Jones Lang LaSalle. Image courtesy of Citizen Schools.

“It’s important that our city has places that anybody can come to no matter what neighborhood you’re coming from,” she said. “They’re important symbols for the entire city.”

It’s these sorts of raw questions that help keep Schneider returning to Citizen Schools. Not only does it challenge her own perspective as an architect, but it brings to light an underlying problem with the industry as a whole. When the diversity scale is so clearly tipped in the direction of the status quo, the realm of ideas that are the result of background and perspective gets severely narrowed.

“I know the numbers are starting to change at least for gender within architecture schools,” she says, “but within the leadership of the profession, we still have a long, long, long way to go—both for gender and, especially, for race and ethnicity.”

A 2005 AIA demographics audit illustrates the lengths the architects will have to go to make their profession reflect the society in which they practice. Only 20.3 percent of architects are female, 2.7 are African-American, 5.6 are Hispanic, and 6.3 are Asian.

For Schneider, one solution is to ensure that more children from under-represented communities understand that the city around them is something they can have a part in creating.

“It’s time that those who design this built world reflect those who live in it,” she says. “As a profession we’re not there yet, but Citizen Schools gives an opportunity to affect that.”

The next generation

Citizen Schools was started in 1995, and John Werner, the program’s chief mobilizing officer, wanted to bring architects into the fold of professionals leading its classes from the get-go.

“We were very passionate about bringing architects in because we think the model-building, representing the built environment, and understanding the community is so important,” he says. “It’s also a good way to show the relevance of math in design and reinforce some of the things that are being taught in the school day.”

A major problem, Werner says, is that kids are dropping out of school because they don’t see the relevance of what they’re doing. By engaging in a hands-on apprenticeship in which they’re learning an actual trade and potential career path, these kids can see how their curriculum applies to the future and also explore career paths they might not have otherwise considered.

For his part, Landsmark knows that programs like this have the ability to bring in more diverse groups to the profession. As assistant to the mayor of Boston, he’d been involved in supporting a number of youth initiatives. “I know that organizations based in communities that sought to connect young people to professional organizations could be very effective in inspiring young people to think about career paths that they might not otherwise have considered,” he says. It also had the effect of helping younger professionals working with the kids get a sense of immediate accomplishment in their work.

Jon Evans and Andy Lantz are just such professionals. Both are in their final semester at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, and both have been involved with Citizen Schools for several semesters. Both say they walk away from classes energized about their chosen career path—no small feat in a time when the industry has slowed.

“I feel like everybody kind of gets the sense of, ‘This is why I wanted to be an architect,’” Evans says. “Having them in this program helps architecture change for the better.”

Lantz points out that a lot of the projects the two have worked on try to focus on issues in the neighborhoods where these students live. A primary reason is to help them see how design impacts an area.

“It’s really fun to show the kids that everything from the scale of a sneaker to a city is designed,” Evans says. “It’s something that they take for granted, and it’s something they should really understand.”

Evans and Lantz found inspiration in their work at Citizen Schools and have taken the cause up to new grade levels by starting Project Link, which serves students at the high school level. Lantz explains the structure is similar to the Citizen Schools program, but the two wanted to get into under-served high schools that typically don’t offer significant arts classes, much less design-specific classes.

“We give them the opportunity to learn that,” he says, “so they can get on track earlier to pursuing design and realizing that their point of view and their perspectives are much more valuable.”

|