Six

Teams Compete to Write a New Chapter of African-American History

and the Final Chapter of the National Mall

The Smithsonian’s National Museum

of African-American History and Culture is blessed with tangled history

and a demanding site

by Zach Mortice

Associate Editor

Summary: The

six design teams short listed for the Smithsonian’s National

Museum of African-American History and Culture are faced with a steep

challenge. As in all quality architecture, each of these challenges

must be made into strength.

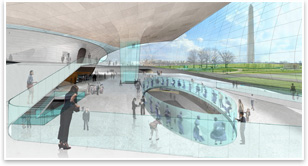

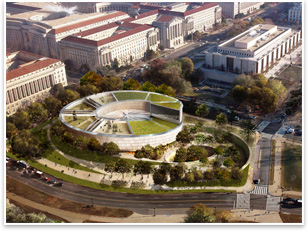

Images courtesy of the Smithsonian.

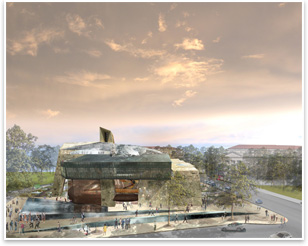

1: Antoine Predock and Moody Nolan’s proposal.

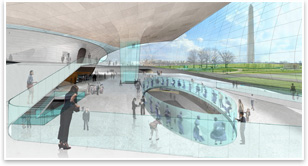

2: Pei Cobb Freed and Partners and Devrouax & Purnell’s design.

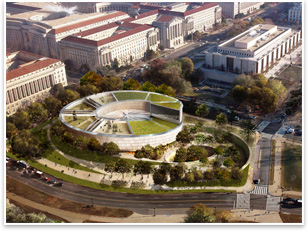

3: Diller Scofidio + Renfro and KlingStubbins’ proposal.

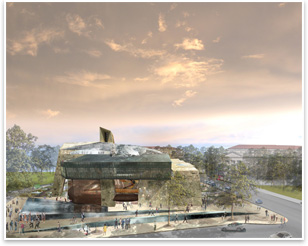

4: Adjaye Freelon Bond and Smith Group’s plan.

5: Foster + Partners and URS’s design.

6: The proposal by Moshe Safdie and Associates and Sultan Campbell Britt & Associates.

A few common motifs emerge from the proposals. Several appropriate

the form of a table to suggest a sense of community and family unity.

The museums’ circulation patterns often present a linear, narrative

journey from slavery to freedom. All the museums present contemporary

conceptions of unprogrammed, open public space with green roof terraces,

landscaped plazas, and outdoor performance spaces. The diversity

of these proposals is most apparent in how they work within, or defy,

the material precedents set by the buildings of John Russell Pope,

James Renwick, and Charles Bullfinch that surround them.

Construction is slated to begin in 2012 and be completed by 2015.

All six teams have at least one minority principal and four firms

are members of the National Organization of Minority Architects.

The museum’s cost is projected to be roughly $500 million,

half of which Congress will provide. An 11-member jury will announce

the winner on April 14.

Whichever design rises from the 5-acre site at the far northwest

corner of the Mall will become the period at the end of its 200-year-long

story. This museum will be the last Smithsonian addition to the Mall

and that’s

likely the most exciting, and risky, challenge of the plan. Architectural

revisionism will have no place in the Mall after the National Museum

of African-American History and Culture.

The primary concern of Antoine

Predock, FAIA and Moody

Nolan’s design is making a monumental

impact on the Mall without a typically monumental presence. This

team’s design is made of a loose assemblage

of natural stone materials, arranged to

appear as a natural, rocky, extension of the land, thus diffusing

the museum’s mass. Instead of celebrating African-American

history and culture with a singular, sculptural, and iconic statement,

this proposal calls for a diverse village of forms that creates a

collaborative and welcoming community while acknowledging the diversity

inherent in its own subject matter. It’s a very contemporary

way to approach a building site, and no other building on the Mall

has ever attempted it, though the rough-hewn golden limestone of

the National Museum of the American Indian has a similar vernacular

material presence. Predock and Moody Nolan’s design also includes

an outdoor amphitheater and restores wetlands on the site, a healing

gesture that acknowledges American history’s debt to African-Americans.

An obelisk-like tower at the top of the building does give the museum

some level of iconic charisma. It also creates a dialogue between

the African-American museum, the Washington Monument, and the African

architects who first pioneered the form of the obelisk thousands

of years ago in Egypt. The primary concern of Antoine

Predock, FAIA and Moody

Nolan’s design is making a monumental

impact on the Mall without a typically monumental presence. This

team’s design is made of a loose assemblage

of natural stone materials, arranged to

appear as a natural, rocky, extension of the land, thus diffusing

the museum’s mass. Instead of celebrating African-American

history and culture with a singular, sculptural, and iconic statement,

this proposal calls for a diverse village of forms that creates a

collaborative and welcoming community while acknowledging the diversity

inherent in its own subject matter. It’s a very contemporary

way to approach a building site, and no other building on the Mall

has ever attempted it, though the rough-hewn golden limestone of

the National Museum of the American Indian has a similar vernacular

material presence. Predock and Moody Nolan’s design also includes

an outdoor amphitheater and restores wetlands on the site, a healing

gesture that acknowledges American history’s debt to African-Americans.

An obelisk-like tower at the top of the building does give the museum

some level of iconic charisma. It also creates a dialogue between

the African-American museum, the Washington Monument, and the African

architects who first pioneered the form of the obelisk thousands

of years ago in Egypt.

The Pei

Cobb Freed & Partners and Devrouax & Purnell design

is the most contextual and respectful of Washington’s

historic Neo-Classical traditions. It presents a comparable amount

of Federal gravitas as the National Gallery of Art, the National

Museum of Natural History, and others, but, like Gordon Bunshaft’s

Hirshhorn Museum, its form is largely determined by the manipulation

of basic geometric shapes. It begins as a square volume, which is

then hollowed and voided. A curvilinear core surrounded by a pond

is added under it, partially sheltered by the hollowed cube’s

roof garden. Its play of void and opacity recalls one of the greatest

works by I.M. Pei, FAIA, the East Building of the National

Gallery of Art, which will also be one of the African-American museum’s

neighbors. The Pei

Cobb Freed & Partners and Devrouax & Purnell design

is the most contextual and respectful of Washington’s

historic Neo-Classical traditions. It presents a comparable amount

of Federal gravitas as the National Gallery of Art, the National

Museum of Natural History, and others, but, like Gordon Bunshaft’s

Hirshhorn Museum, its form is largely determined by the manipulation

of basic geometric shapes. It begins as a square volume, which is

then hollowed and voided. A curvilinear core surrounded by a pond

is added under it, partially sheltered by the hollowed cube’s

roof garden. Its play of void and opacity recalls one of the greatest

works by I.M. Pei, FAIA, the East Building of the National

Gallery of Art, which will also be one of the African-American museum’s

neighbors.

Diller

Scofidio + Renfro’s proposal,

in association with KlingStubbins,

pushes form and materials on the Mall ahead the furthest. Their “Stone

Cloud” design is a table-like form that rises up from the ground

on four legs over a pedestrian trail that feeds into the museum.

It’s primarily made of limestone, like many of its serious

and honorific neighbors, but this limestone is sculpted with organic

curves made possible by computerized fabrication technology that

give it an otherworldly presence, reinforced by the glass

façade the entire building will be wrapped in. Large, ocular

windows break up its otherwise unadorned facades. Inside, a dark,

richly textural space called the “Culture Core” balances

the pale limestone on the outside. This material juxtaposition echoes

the team’s presentation of W.E.B. Dubois’ ideas about

African-American identity as a double consciousness born of separation. Diller

Scofidio + Renfro’s proposal,

in association with KlingStubbins,

pushes form and materials on the Mall ahead the furthest. Their “Stone

Cloud” design is a table-like form that rises up from the ground

on four legs over a pedestrian trail that feeds into the museum.

It’s primarily made of limestone, like many of its serious

and honorific neighbors, but this limestone is sculpted with organic

curves made possible by computerized fabrication technology that

give it an otherworldly presence, reinforced by the glass

façade the entire building will be wrapped in. Large, ocular

windows break up its otherwise unadorned facades. Inside, a dark,

richly textural space called the “Culture Core” balances

the pale limestone on the outside. This material juxtaposition echoes

the team’s presentation of W.E.B. Dubois’ ideas about

African-American identity as a double consciousness born of separation.

The proposal by Adjaye Freelon Bond and

SmithGroup blends

African and Neo-Classical American iconography in a design that displays

the clever hand of David Adjaye, Hon. FAIA, with materials and basic

geometric forms. This three-tired plan is composed of a rectilinear

base level and two trapezoidal sections on top, inspired by West

African Yoruban crowns and the tripartite organization (base, shaft,

capital) of a classical column. Both trapezoidal sections are covered

in a perforated, bronze-clad corona that emits light into the museum.

Cantilevering “gallery

lenses” take

visitors out of the regular circulation of the museum and show them

views across the exhibit floors and outside. Inside the base volume,

the central hall ceiling is covered in vertically suspended planks

of wood meant to convey heaviness and oppression. Alternately, these

planks are lit from above to form a glowing cloud, communicating

optimism, joy, and the chapters of African-American history that

have yet to be written. The proposal by Adjaye Freelon Bond and

SmithGroup blends

African and Neo-Classical American iconography in a design that displays

the clever hand of David Adjaye, Hon. FAIA, with materials and basic

geometric forms. This three-tired plan is composed of a rectilinear

base level and two trapezoidal sections on top, inspired by West

African Yoruban crowns and the tripartite organization (base, shaft,

capital) of a classical column. Both trapezoidal sections are covered

in a perforated, bronze-clad corona that emits light into the museum.

Cantilevering “gallery

lenses” take

visitors out of the regular circulation of the museum and show them

views across the exhibit floors and outside. Inside the base volume,

the central hall ceiling is covered in vertically suspended planks

of wood meant to convey heaviness and oppression. Alternately, these

planks are lit from above to form a glowing cloud, communicating

optimism, joy, and the chapters of African-American history that

have yet to be written.

Linear circulation patterns manipulated to fit onto the museum’s

site are used to communicate the symbolic, narrative journey of African-Americans

in Foster

+ Partners and URS’s proposal.

This design begins by bringing visitors down through a curving landscaped

plaza to the museum’s entrance below grade. They enter, shrouded

in darkness and presented with exhibits that focus on the equally

dark history of African-Americans’ first experiences with America.

As the museum progresses, patrons move gradually upward and witness

African-Americans’ historic struggle and epic victories. The museum wraps this linear,

skyward journey around itself, curving a rectilinear bar into a coiled

infinity loop. The path terminates at an observation deck window

that looks out over Washington, D.C., capital city of the free world. Linear circulation patterns manipulated to fit onto the museum’s

site are used to communicate the symbolic, narrative journey of African-Americans

in Foster

+ Partners and URS’s proposal.

This design begins by bringing visitors down through a curving landscaped

plaza to the museum’s entrance below grade. They enter, shrouded

in darkness and presented with exhibits that focus on the equally

dark history of African-Americans’ first experiences with America.

As the museum progresses, patrons move gradually upward and witness

African-Americans’ historic struggle and epic victories. The museum wraps this linear,

skyward journey around itself, curving a rectilinear bar into a coiled

infinity loop. The path terminates at an observation deck window

that looks out over Washington, D.C., capital city of the free world.

The sensuously curving butterfly wing entry pavilion in the Moshe

Safdie and Associates design is equated

with Africa and stands separate from the rest of the museum, accessible

from the upper levels via a skywalk as a distant vista of origin,

separate from the life of the museum itself. Light reaches deep into

the museum (designed in association with Sultan

Campbell Britt & Associates)

through its front glass curtain wall. Much of the building lies underground,

which reduces the building’s footprint. In the rear, a section

of the museum is cut away for a glass pavilion that is on axis with

the front pavilion and the Washington Monument. This rear pavilion

contains long vertical strips that run the height of the museum,

tapering as they rise, to create a womb-like space that honors the

creative vitality with which African-Americans have infused American

culture. The sensuously curving butterfly wing entry pavilion in the Moshe

Safdie and Associates design is equated

with Africa and stands separate from the rest of the museum, accessible

from the upper levels via a skywalk as a distant vista of origin,

separate from the life of the museum itself. Light reaches deep into

the museum (designed in association with Sultan

Campbell Britt & Associates)

through its front glass curtain wall. Much of the building lies underground,

which reduces the building’s footprint. In the rear, a section

of the museum is cut away for a glass pavilion that is on axis with

the front pavilion and the Washington Monument. This rear pavilion

contains long vertical strips that run the height of the museum,

tapering as they rise, to create a womb-like space that honors the

creative vitality with which African-Americans have infused American

culture.

|

The primary concern of

The primary concern of  The

The  Diller

Scofidio + Renfro’s

Diller

Scofidio + Renfro’s The proposal by

The proposal by  Linear circulation patterns manipulated to fit onto the museum’s

site are used to communicate the symbolic, narrative journey of African-Americans

in

Linear circulation patterns manipulated to fit onto the museum’s

site are used to communicate the symbolic, narrative journey of African-Americans

in  The sensuously curving butterfly wing entry pavilion in the

The sensuously curving butterfly wing entry pavilion in the