Site, Materials, and Form Flow Together in Studio Gang’s Aqua Tower Site, Materials, and Form Flow Together in Studio Gang’s Aqua TowerJeanne Gang’s tower puts elegant waves of concrete in the service of strict contextual specificity How do you . . . design a skyscraper through a contextually mediated process that still manages to be expressive architecture? Summary: Though aesthetically vivid and sculptural, Aqua Tower’s form was created through a structured, systematic process of addressing site constraints. Its composition method expresses architect Jeanne Gang’s nuanced interpretations of material honesty and construction methodologies. Jeanne Gang, AIA, began the design of Aqua Tower in Chicago with a simple question of Miesian material honesty: How best to express outwardly the building’s internal structural skeleton—a conventional system of columns and slabs of reinforced concrete? “I always start with materials,” she says. “What is this going to be made of?” But by reveling in the individual personalities of her materials and rigorously working through site constraints and design goals, she and her firm Studio Gang Architects arrived at a form that delicately balances austere, Modernist expression with freehand form-giving. Her glass and concrete terraced tower promises to be one of the most eye-catching skyscrapers in recent memory in Chicago, the city that gave birth to the form. The 82-story, residential and hotel tower should be no less memorable for Gang herself. It’s the first time she’s worked with commercial real-estate developers, her first high rise, and likely the first skyscraper to be authored so completely by a woman.

The tower is owned by Magellan Development, and Gang’s firm is working with Lowenberg Associates, the architect of record. The 1.9 million-square-foot tower will have 228,000 square feet of hotel rooms at its base, 485,000 square feet of rental residence units on the middle floors, and 390,000 square feet of for-sale condominiums at the top. The skyscraper’s base is clad in handmade cementitious plaster, and its ground level contains retail space, a hotel ballroom, and a restaurant. Its second floor will be used for commercial office space, topped by a green roof complete with lounge space, pool, and running track. The tower’s main entrance sits under a curved and cantilevered upturned lip, all modeled after the smaller terraced balconies that hang above the base.

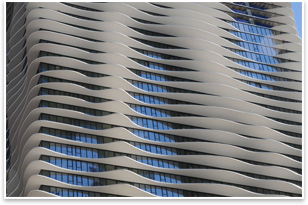

As with much of Chicago-based Studio Gang Architects’ body of work, sustainability is a primary design focus, so Gang and her team refined the terrace extensions to maximize solar shading. Sustainable features also will include rainwater collection systems and energy-efficient lighting. The green roof on top of the tower base will be the biggest in Chicago, Gang says. The tower will seek LEED certification. Next, Studio Gang adjusted the floor slab extensions to accommodate individual unit floor plans. The most aesthetically driven part of the process came last: blending the terraces together to form smooth liquid transitions between and across floors. In the end, each floor has a unique set of terraces.

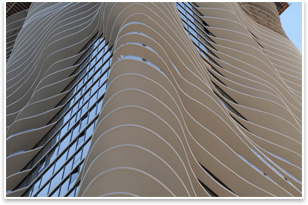

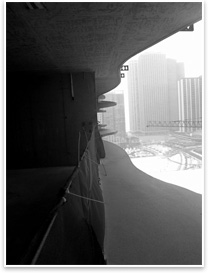

“For me, that is design,” Gang says. “It’s not about drawing a cartoon icon. It’s about the coordination and choreography of taking all these restraints and criteria and orchestrating a form from that. “I was interested in making a topographic, specific high-rise, as opposed to a universal, iconic high-rise. It’s interesting how this building related specifically to this site. If you did it again somewhere else, it would be different because there would be different things to relate to.” Gang isn’t talking about general platitudes of adjacent building stock, history, demographics, and economy. Aqua Tower’s every arc and curve of its terraces is an explicit reaction to the forms that surround it. Each terrace is an extension of the 9-inch concrete floor slabs, which taper to 6 inches at the balconies’ edge. They were all poured in place on top of a table system and shaped by a flexible steel edge that can be reused to make different shapes. Gang and the tower’s builders are using a robotic survey tool that is able to load construction drawings and lay them out almost instantly. “At first, we were thinking they were going to come within a tolerance of 4-5 inches, but it’s really dead on,” she says. “We’ve found that there’s no variation between what was drawn and what gets laid out.” Gang says this digital efficiency helped her stay on budget with the project’s developer, saving time and money for extra materials. The tower’s unique design brought Gang and her team another money-saving bonus. They found that they could save over a million dollars by forgoing the building’s sway dampening system, because the parallel terraces diffused horizontal wind loads.

“It’s the same with the Aqua Tower. It’s an organic process,” she says—revealing a deep understanding of the material composition and construction that binds manmade and natural materials in their most irreducible elements. |

||

Copyright 2008 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Best New Skyscraper of 2006 Stands in New York City

› Great American Building to Become Cincinnati Skyline Beacon

› Joining Man and Woman with Steel and Glass

› Perforated Façade Defines New Dubai Tower

Visit Studio Gang Architects Web site.

Read an appraisal of Aqua Tower’s initial design by Blair Kamin, Hon. AIA, of the Chicago Tribune.

See what the Committee on Design Knowledge Community is up to.

Do you know SOLOSO?

The AIA’s resource knowledge base can connect you to “Can High Rise Create Livable Cities? Vancouver and Miami”, a presentation on how high-rise, high-density development is remaking the contemporary cities.

See what else SOLOSO has to offer for your practice.

From the AIA Bookstore: Skyscraper Playing Cards

Captions

1. The terraced balconies in Aqua Tower move in waves and ripples across its façade. Rendering by Image Fiction.

2. Each balcony is an extension of the concrete floor slab. Photo © Studio Gang Architects.

3. Aqua Tower is slated to be complete by early 2010. Photo © Studio Gang Architects.

4. The balconies are designed to maximize views into the city. Photo © Studio Gang Architects.

5. The Aqua Tower under construction. Photo © Studio Gang Architects.

Liquid stone

Liquid stone Site by site, constraint by constraint

Site by site, constraint by constraint Long on contextual restraints

Long on contextual restraints Mineral construction

Mineral construction