Brick by Brick, Door by Door, Beam by Beam, the Wing Luke Asian Museum Retells the Stories of Seattle’s Asian Immigrants

With a reluctant preservationist’s hand, Olson Sundberg Kundig Allen Architects leave the museum intact by tearing down a wall

by Zach Mortice

Associate Editor

How do you . . . renovate an early 20th century building into a hybrid community center–museum facility that references its previous programs? How do you . . . renovate an early 20th century building into a hybrid community center–museum facility that references its previous programs?

Summary: The Wing Luke Asian Museum in Seattle revives the 1910 East Kong Yick building as a museum and community center. The building separates its diverse programs by differing levels of active use and applies 2009 AIA Firm Award recipient Olson Sundberg Kundig Allen’s trademark juxtaposition of raw and natural handcrafted materials (many harvested from the building before its renovation) with refined and contemporary ones.

View the photo gallery

Photos courtesy of the architect.

1. The front façade of the Wing Luke Asian Museum.

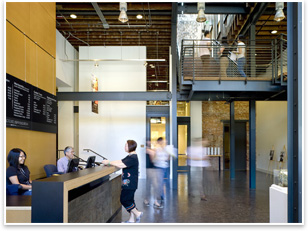

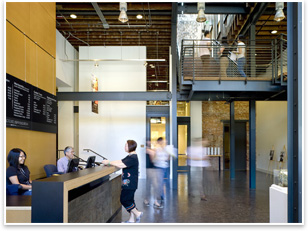

2. The reception area and main hall of the museum.

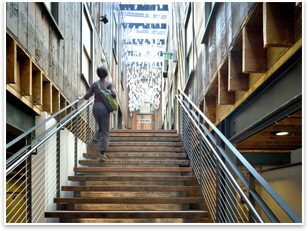

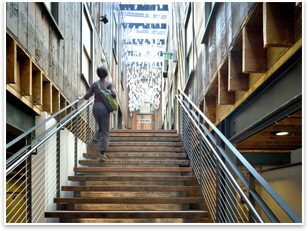

3. Exposed and reclaimed wood is used in the light well corridors.

4. A historical “immersion” exhibit that models rooms after original uses in the East Kong Yick building.

Tom Kundig: Houses, edited by Dung Ngo with Steven Holl, AIA, Rick Joy, AIA, and Billie Tsien, AIA (Princeton Architectural Press, 2006). Tom Kundig: Houses, edited by Dung Ngo with Steven Holl, AIA, Rick Joy, AIA, and Billie Tsien, AIA (Princeton Architectural Press, 2006).

In their design for the Wing Luke Asian Museum in Seattle’s Chinatown and in the rest of their work, Olson Sundberg Kundig Allen Architects are known for their craftsman-like affection for natural, raw materials presented honestly. The new home for the Wing Luke Asian Museum, which opened in May of 2008, is a renovated 1910 building that is packed with this kind of potential—simple and transparently presented materials, aged to rich maturity.

But that wasn’t how Rick Sundberg, FAIA, the principal-in-charge of the project, was used to working. “I was really nervous about it,” he says. “Most of my work is really tailored. I’m not a preservationist by any stretch of the imagination.”

Instead of building in the organic textural richness that has become his firm’s hallmark, Sundberg had instead to sit back, relax, and peel off layers of the building to reveal its imperfectly unique wood-grained character—and story. “The more I thought about it, the more I wanted the building to be the story, not necessarily the architecture, or the big, architectonic idea,” he says. “I like that the building itself was a big part of the story of Chinese immigration.”

An investment in culture and community

The Wing Luke Museum’s new home (its much smaller previous facility was located a block away) is the East Kong Yick building. It was funded by 170 Chinese immigrants at the beginning of the 20th century and designed by the Seattle architecture firm of Thompson and Thompson. The three-story, red brick building was a true mixed-use hub of life. It was used for hotel rooms, residences, shop fronts, and family association meeting rooms, where people from the same region of their native country with the same family name would gather. Generations of immigrants from China, Japan, and the Philippines called the building a home, work, and community center.

The building was closed and largely abandoned in the 1970s, when it didn’t meet the city’s safety codes. To bring it back to life, Seattle-based Olson Sundberg Kundig Allen Architects had to fit in multitude of programs that would rival its previous incarnation in diversity and complexity. It is common today to design museums with aspirations of creating civic and community-centered places that explain how visitors truly have a vested interest in their culture, but Sundberg’s Wing Luke Museum completely fulfills this goal purely through its program. It contains contemporary art exhibits for emerging Asian Pacific artists, “immersion” galleries of historic immigrant set pieces like restored apartments and storefronts, community center meeting and event spaces, and a family history research center. The building was closed and largely abandoned in the 1970s, when it didn’t meet the city’s safety codes. To bring it back to life, Seattle-based Olson Sundberg Kundig Allen Architects had to fit in multitude of programs that would rival its previous incarnation in diversity and complexity. It is common today to design museums with aspirations of creating civic and community-centered places that explain how visitors truly have a vested interest in their culture, but Sundberg’s Wing Luke Museum completely fulfills this goal purely through its program. It contains contemporary art exhibits for emerging Asian Pacific artists, “immersion” galleries of historic immigrant set pieces like restored apartments and storefronts, community center meeting and event spaces, and a family history research center.

Into the attic

The new 57,000-square-foot Wing Luke Museum, which bills itself as “America’s premier pan-Asian Pacific American museum,” dips below grade across its front streetward face. Sundberg says his firm’s $11 million renovation effort required replacing a few sections of the buildings masonry. Window designer Loewen recreated windows that mimicked the building’s originals. Visitors enter the museum under an abstractly Asian fanned awning by sculptor Gerard Tsutakawa. Inside the double-height welcome hall (the museum’s primary gathering and circulation space), they are greeted by a reception desk clad in murky green-gray hammered-tin panels that came from the building’s original doors. A right-angled plywood mass wraps around half of the reception desk, and similarly colored panels of medium-density fiberboard on the wall behind the desk illustrate Olson Sundberg Kundig Allen’s penchant for balancing processed, contemporary materials with natural and handcrafted ones.

On the first floor, a small theater, museum store, and two contemporary exhibit galleries essentially are designed as simple, spare white box spaces. There are also two “immersion” historic exhibits, one of which recreates a period mercantile shop, and another that represents a 1920s apartment. Sundberg says he wasn’t shy about using Li-Saltzman Architects’ Tenement Museum in New York as inspiration for these rooms. In some situations, the placement of programs refers back to the building’s original life—retail spaces are located where they previously were, and the original family association rooms will become family association exhibits. On the first floor, a small theater, museum store, and two contemporary exhibit galleries essentially are designed as simple, spare white box spaces. There are also two “immersion” historic exhibits, one of which recreates a period mercantile shop, and another that represents a 1920s apartment. Sundberg says he wasn’t shy about using Li-Saltzman Architects’ Tenement Museum in New York as inspiration for these rooms. In some situations, the placement of programs refers back to the building’s original life—retail spaces are located where they previously were, and the original family association rooms will become family association exhibits.

Fir timbers from the building’s renovation were refashioned into stairs that lead to the second and third floors. This staircase lies under wide and deep light wells that form the design centerpiece of the project. Visitors walk up these stairs between exposed fir load-bearing walls that were left in place after metal siding was removed. The tactile image of century-old splintered wood, the feeling of ascent while being bathed in natural light, and the simple geometries of the load-bearing wood structure suggest the feeling of visiting an attic of cultural secrets, a place full of stories not told enough.

As visitors climb these stairs, they leave behind the noisy and bustling ground floor and enter more serene upper floor programs. “As you’re moving up, the building becomes more quiet, more contemplative,” Sundberg says. Although for the most part the architects resisted the temptation to wall these diverse programs off from each other to maintain their integrity, they did vary the placement of programs by their level of active use. Main gathering and circulation spaces are downstairs, while most historical immersion spaces and art galleries are upstairs, along with the museum’s family history research center. On the second and third floors, this sense of intimate and quiet scaling is reinforced by narrow corridors and modest rooms, meant to convey the compressed living space and transformatively optimistic possibilities of the immigrant experience. As visitors climb these stairs, they leave behind the noisy and bustling ground floor and enter more serene upper floor programs. “As you’re moving up, the building becomes more quiet, more contemplative,” Sundberg says. Although for the most part the architects resisted the temptation to wall these diverse programs off from each other to maintain their integrity, they did vary the placement of programs by their level of active use. Main gathering and circulation spaces are downstairs, while most historical immersion spaces and art galleries are upstairs, along with the museum’s family history research center. On the second and third floors, this sense of intimate and quiet scaling is reinforced by narrow corridors and modest rooms, meant to convey the compressed living space and transformatively optimistic possibilities of the immigrant experience.

Preserving stories

During the building’s renovation, Sundberg’s preservationist zeal became so great that he issued a new rule: “Nothing leaves the building.” Every piece and component was to be evaluated for reuse in the new design—offering each slab of wood or sheet of metal the chance to survive its new configuration to keep telling the story of the aspiring Americans who built them. |

How do you . . .

How do you . . .

On the first floor, a small theater, museum store, and two contemporary exhibit galleries essentially are designed as simple, spare white box spaces. There are also two “immersion” historic exhibits, one of which recreates a period mercantile shop, and another that represents a 1920s apartment. Sundberg says he wasn’t shy about using Li-Saltzman Architects’ Tenement Museum in New York as inspiration for these rooms. In some situations, the placement of programs refers back to the building’s original life—retail spaces are located where they previously were, and the original family association rooms will become family association exhibits.

On the first floor, a small theater, museum store, and two contemporary exhibit galleries essentially are designed as simple, spare white box spaces. There are also two “immersion” historic exhibits, one of which recreates a period mercantile shop, and another that represents a 1920s apartment. Sundberg says he wasn’t shy about using Li-Saltzman Architects’ Tenement Museum in New York as inspiration for these rooms. In some situations, the placement of programs refers back to the building’s original life—retail spaces are located where they previously were, and the original family association rooms will become family association exhibits. As visitors climb these stairs, they leave behind the noisy and bustling ground floor and enter more serene upper floor programs. “As you’re moving up, the building becomes more quiet, more contemplative,” Sundberg says. Although for the most part the architects resisted the temptation to wall these diverse programs off from each other to maintain their integrity, they did vary the placement of programs by their level of active use. Main gathering and circulation spaces are downstairs, while most historical immersion spaces and art galleries are upstairs, along with the museum’s family history research center. On the second and third floors, this sense of intimate and quiet scaling is reinforced by narrow corridors and modest rooms, meant to convey the compressed living space and transformatively optimistic possibilities of the immigrant experience.

As visitors climb these stairs, they leave behind the noisy and bustling ground floor and enter more serene upper floor programs. “As you’re moving up, the building becomes more quiet, more contemplative,” Sundberg says. Although for the most part the architects resisted the temptation to wall these diverse programs off from each other to maintain their integrity, they did vary the placement of programs by their level of active use. Main gathering and circulation spaces are downstairs, while most historical immersion spaces and art galleries are upstairs, along with the museum’s family history research center. On the second and third floors, this sense of intimate and quiet scaling is reinforced by narrow corridors and modest rooms, meant to convey the compressed living space and transformatively optimistic possibilities of the immigrant experience.