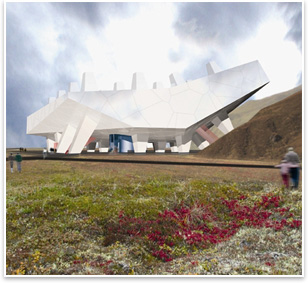

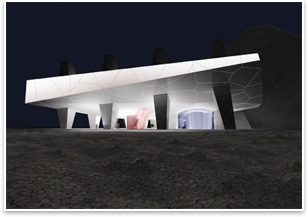

| Home at Last—Ice Age Mammoth Gets Permanent Digs in Russian Permafrost Museum World Mammoth and Permafrost Museum set to open in Siberia in 2009 How Do You . . . design a world-class science center featuring a frozen, mammoth, and still-buried prehistoric beast. Summary: The remains of a wooly mammoth, an ancient relative of elephants, preserved in permanently frozen soil—permafrost—will now be researched and displayed at the World Mammoth and Permafrost Museum in the city of Yakutsk in Siberia. New York City-based Leeser Architecture will create a sloping, angular complex elevated at the base of a mountain called the Tchoutchour Mouran. The site will be elevated 20 feet above ice on cone-shaped stilts to keep it insulated from the surface permafrost. Inside, visitors can “float” upwards on a tube escalator and observe scientists while being surrounded by sloping gardens. The museum, scheduled to open in 2009, will be energy efficient and ecological, the architects say, with research facilities, exhibit galleries, and an underground permafrost gallery displaying the remains of the Siberian wooly mammoth.

Sitting in ice

“The building floats,” describes Leeser. “You enter going up an air lock onto an open, elevated metal grid, and proceed onto a suspended, climate-controlled escalator. As you go up, you pass, or ‘float,’ through the lab level, where there is an outer ring of labs. Visitors will be able to see the scientists but will not be able to get off there because the work they do is sensitive to contamination. Visitors then vertically pass the inner core, which is the storage, and above that level is the large, open museum level. On the museum level there will be conference rooms, a media room, and a café that projects out onto east and west gardens that slope up into the garden. The outer edge is the exhibition part of the museum, and the columns project thru that space.”

From the first level, another escalator will allow visitors to descend inside the base of the mountain into the permafrost gallery. “The escalator goes down to a series of ice caves that house the most complete mammoth ever found,” enthuses Leeser. “The mammoth will remain in the caves, so the museum is the portal to the caves. The access to the cave will be highly restrictive because only a few people at any given time are allowed into it. Too much heat would deteriorate the mammoth and melt the ice.” |

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Cleared for Landing

› Smithsonian American History Museum Undergoing Makeover

› Daniel Boone Wilderness Road Interpretative Center Blazes Forward

Did you know . . .

• Yakutsk is a town of extreme weather conditions, Leeser points out, with records for the biggest difference in terms of the coldest and hottest temperatures. Yakutsk is one of the coldest cities on the planet, with January temperatures averaging -45˚ F. But July temperatures can exceed 90˚.

• Yakutsk is the biggest city built on permafrost. Most houses are built on concrete piles.

• Most wooly mammoth remains are in Siberia. They had tusks up to 16 feet long that curved. While not certain, researchers suspect that the wooly mammoth used the tusks to shovel snow to get to the vegetation below.

• There are different types of permafrost. Continuous permafrost, such as in Siberia, is frozen soil that becomes ice. If the temperature is just below the freezing point, discontinous permafrost results, which is part soil, part ice. Sporadic permafrost occurs when permafrost covers less than 50 percent of the landscape, usually when mean annual temperatures are between 32˚ and 28˚F.