The Nature of Nature

Tom Kundig, FAIA, receives National Architecture Design Award from Smithsonian's Cooper-Hewitt Design Museum

by Russell Boniface

Associate Editor

How do you … design small and large buildings to integrate with the landscape? How do you … design small and large buildings to integrate with the landscape?

Summary: Tom Kundig, FAIA, partner in Seattle-based Olson Sundberg Kundig Allen Architects, has been honored with a Smithsonian’s Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum 2008 National Design Award in architecture design for integrating architecture and landscape in both small and large projects. Kundig, a native of the Northwest, has always preferred being outside to inside, he reflects, citing this as the influence on his architecture. He grew up in eastern Washington and Northern Idaho in a landscape of mountains, deserts, rivers, and high skies. “My childhood was about being outside,” he recalls. “So here I am as an architect designing for buildings where … the building is the line—the veneer—between outside and inside.“

Kundig incorporates that relationship in his work, he says, whether it’s a small or large project. He does have a fondness for the smaller projects and even tells students to embrace them, but he maintains a balance. What’s important, he enthuses, is that the project integrate with the landscape.

“I’ve always said that I don’t think I can design anything more beautiful than the natural landscape,” he says. “The source of what we think is beautiful and authentic is from our experience in the natural world, regardless if we are in a big city or in the countryside. We are all influenced by the natural world around us. For me, architecture is about embracing the natural landscapes, whether that’s a city or country, I think the nature of nature will play a big role in the buildings I’m going to do.” “I’ve always said that I don’t think I can design anything more beautiful than the natural landscape,” he says. “The source of what we think is beautiful and authentic is from our experience in the natural world, regardless if we are in a big city or in the countryside. We are all influenced by the natural world around us. For me, architecture is about embracing the natural landscapes, whether that’s a city or country, I think the nature of nature will play a big role in the buildings I’m going to do.”

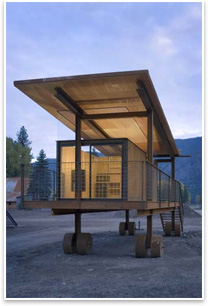

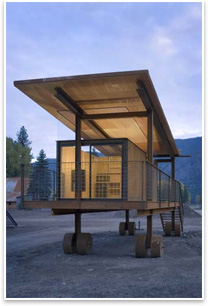

Kundig calls it an affinity for the outside from the inside, and the inside from the outside. “I get hired by people who want that relationship. It’s sensitivity to the context of the nature of a place. Some of my projects are so small because the owner would probably prefer being outside than inside, just like me. The building becomes like a tree house in a big landscape. If the house is relatively small, you are going to sense that landscape around you, more than if the house becomes relatively large and you start putting layers between the inside and the nature of the landscape on the outside. It’s natural for me to relate through that line between the inside and the outside.”

Connection with the environment, the clients, and natural materials Connection with the environment, the clients, and natural materials

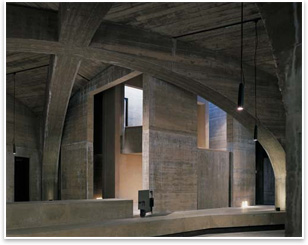

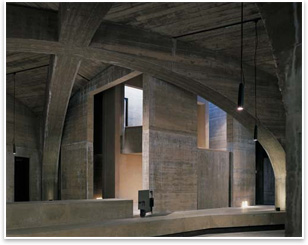

His projects include small structures in the Northwest desert that resemble small cabins and function as homes, offices, and even as a pool house. The essential elements of the design are that they respond to the surrounding environment, reflect the personalities of the client, and incorporate natural materials such as timber or are elements such as steel, concrete, and glass that are made from natural materials.

“Materials in their raw state fit into the idea of the authenticity of building materials relating to the nature of nature,” he explains. “Nature is the state of authenticity. When the materials of nature are left to age naturally—whether it’s bark, steel, concrete, or glass—left to their own devices they becomes more beautiful. It’s the nature of time. I think leaving materials on buildings in their natural states allows them to become more beautiful in time, rather than being so crisp and clean. It’s almost a bit of arrogance to think that our materials will remain pristine and perfect, as if you were taking on the nature of nature and the natural processes.” “Materials in their raw state fit into the idea of the authenticity of building materials relating to the nature of nature,” he explains. “Nature is the state of authenticity. When the materials of nature are left to age naturally—whether it’s bark, steel, concrete, or glass—left to their own devices they becomes more beautiful. It’s the nature of time. I think leaving materials on buildings in their natural states allows them to become more beautiful in time, rather than being so crisp and clean. It’s almost a bit of arrogance to think that our materials will remain pristine and perfect, as if you were taking on the nature of nature and the natural processes.”

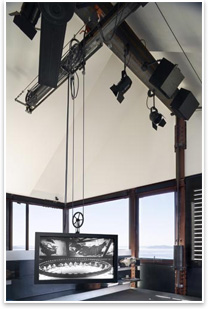

A project’s personal spirit

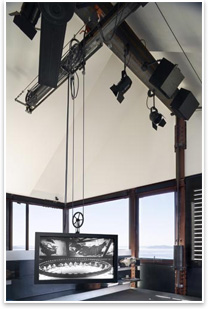

Kundig sometimes reassembles existing parts to reinvent structural elements such as doors, windows, and stairs. An example is the Hot Rod House, Seattle, a home he designed for himself that reassembles car parts for various interior elements. “It’s the idea that parts and pieces that we move, shape, touch, and experience every day can be reassembled. The house is a wink and a nod to the ‘Hot Rod’ culture; that you can personalize and reinvent the parts and pieces provided by a larger industry. It brings a personal spirit to the project.”

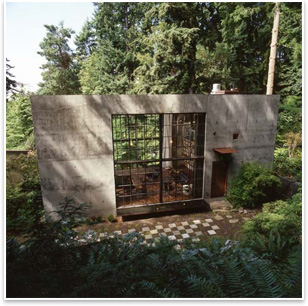

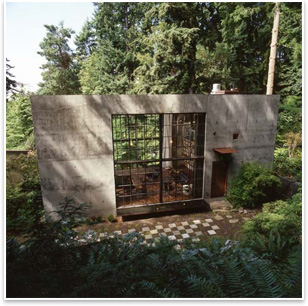

That’s true of his other projects, such as his Seattle Studio House of concrete and glass. “The intention is to pick up subtle cues that this is a place meaningful to the people who live there, to provide their own personal spirit. Studio House is the first house for me to engage the client on that personal level of understanding and embracing the idea that when you work on a building you are making the personality and DNA of the group. It’s about the craftspeople, the contractor, and the owner. Hopefully, people recognize that each house has its own special spirit and attitude.” That’s true of his other projects, such as his Seattle Studio House of concrete and glass. “The intention is to pick up subtle cues that this is a place meaningful to the people who live there, to provide their own personal spirit. Studio House is the first house for me to engage the client on that personal level of understanding and embracing the idea that when you work on a building you are making the personality and DNA of the group. It’s about the craftspeople, the contractor, and the owner. Hopefully, people recognize that each house has its own special spirit and attitude.”

Winning the award

Kundig says he is honored to win the Cooper-Hewitt award. “I was stunned,” he says. “What’s terrific is that it’s for a body of work. Cooper Hewitt is a particular honor for me because it is not just a jury of architects but it’s a jury made up of industrial and product designers; car designers; and fashion, glass, and graphic designers. It’s a deep honor to be recognized by a group that transcends our industry and has an effect with their industry.

“For me, the award couldn’t be more meaningful. I grew up with artists, so the most compelling part of architecture for me is that it pulls from different spirits, whether its music, poetry, sculpture, photography, or science, since I think the nature of how things work is inherently beautiful and authentic. It’s about the poetry of art and also the driving function of what we are trying to do, whether it’s sustainability, or how you live and move in these places. You can’t pick a better place to be than doing architecture.” “For me, the award couldn’t be more meaningful. I grew up with artists, so the most compelling part of architecture for me is that it pulls from different spirits, whether its music, poetry, sculpture, photography, or science, since I think the nature of how things work is inherently beautiful and authentic. It’s about the poetry of art and also the driving function of what we are trying to do, whether it’s sustainability, or how you live and move in these places. You can’t pick a better place to be than doing architecture.”

|

How do you …

How do you …  “I’ve always said that I don’t think I can design anything more beautiful than the natural landscape,” he says. “The source of what we think is beautiful and authentic is from our experience in the natural world, regardless if we are in a big city or in the countryside. We are all influenced by the natural world around us. For me, architecture is about embracing the natural landscapes, whether that’s a city or country, I think the nature of nature will play a big role in the buildings I’m going to do.”

“I’ve always said that I don’t think I can design anything more beautiful than the natural landscape,” he says. “The source of what we think is beautiful and authentic is from our experience in the natural world, regardless if we are in a big city or in the countryside. We are all influenced by the natural world around us. For me, architecture is about embracing the natural landscapes, whether that’s a city or country, I think the nature of nature will play a big role in the buildings I’m going to do.” Connection with the environment, the clients, and natural materials

Connection with the environment, the clients, and natural materials

That’s true of his other projects, such as his Seattle Studio House of concrete and glass. “The intention is to pick up subtle cues that this is a place meaningful to the people who live there, to provide their own personal spirit. Studio House is the first house for me to engage the client on that personal level of understanding and embracing the idea that when you work on a building you are making the personality and DNA of the group. It’s about the craftspeople, the contractor, and the owner. Hopefully, people recognize that each house has its own special spirit and attitude.”

That’s true of his other projects, such as his Seattle Studio House of concrete and glass. “The intention is to pick up subtle cues that this is a place meaningful to the people who live there, to provide their own personal spirit. Studio House is the first house for me to engage the client on that personal level of understanding and embracing the idea that when you work on a building you are making the personality and DNA of the group. It’s about the craftspeople, the contractor, and the owner. Hopefully, people recognize that each house has its own special spirit and attitude.” “For me, the award couldn’t be more meaningful. I grew up with artists, so the most compelling part of architecture for me is that it pulls from different spirits, whether its music, poetry, sculpture, photography, or science, since I think the nature of how things work is inherently beautiful and authentic. It’s about the poetry of art and also the driving function of what we are trying to do, whether it’s sustainability, or how you live and move in these places. You can’t pick a better place to be than doing architecture.”

“For me, the award couldn’t be more meaningful. I grew up with artists, so the most compelling part of architecture for me is that it pulls from different spirits, whether its music, poetry, sculpture, photography, or science, since I think the nature of how things work is inherently beautiful and authentic. It’s about the poetry of art and also the driving function of what we are trying to do, whether it’s sustainability, or how you live and move in these places. You can’t pick a better place to be than doing architecture.”