Ten Museum Park: Mies at the Beach

More warm-weather Modernism takes off in Miami

by Zach Mortice by Zach Mortice

Associate Editor

Summary: OPPENheim Architecture + Design’s Ten Museum Park adapts Modernist ideas about structural honesty and minimalist construction and applies them to a luxury beachfront site. The condominium tower wears a gridded exoskeleton that appears as a decorative design element while still working as structural support, illustrating the building’s commitment to minimalism and seaside residential opulence.

How do you … design a luxury condominium tower on a beachfront site that appropriates Modernist ideas about form?

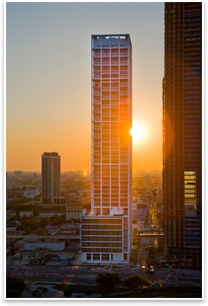

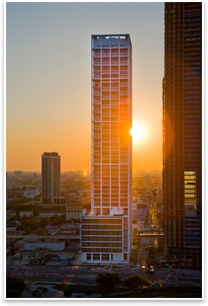

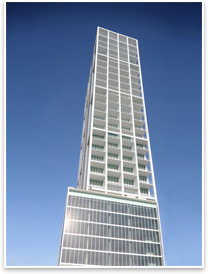

Located on the Miami coast, looking over Biscayne Bay and the Atlantic Ocean, the Ten Museum Park condominiums looks like nothing so much as a stolid, cold-weather Miesian highrise that’s doffed its steel-grid parka to wade across a beach. Like its classically Modernist forebears, Ten Museum Park’s structure and floor plans are expressed honestly and literally through its façade of glass, concrete, and stucco. Located on the Miami coast, looking over Biscayne Bay and the Atlantic Ocean, the Ten Museum Park condominiums looks like nothing so much as a stolid, cold-weather Miesian highrise that’s doffed its steel-grid parka to wade across a beach. Like its classically Modernist forebears, Ten Museum Park’s structure and floor plans are expressed honestly and literally through its façade of glass, concrete, and stucco.

“With all our architecture, we let the logic express itself [and] become the façade,” says Chad Oppenheim, AIA, founder and principal of OPPENheim Architecture + Design. “The façade is an expression of that internal logic.”

But in place of the heavy steel that the Lever House and Seagram Building wear to survive New York winters, Oppenheim’s building opts for lithe and breezy concrete framing that conveys hedonistic refinement rather than a brawny air of New Order confrontation. It’s a sensibility that has risen above the current Miami condo market. Nearly 90 percent of its units have sold while the rest of the city has been mired in the worst condo bust in decades.

Two towers, two sensibilities Two towers, two sensibilities

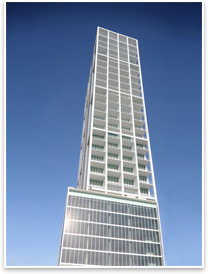

Oppenheim’s 608,000-square-foot tower rises up 50 stories over a mixed-use, rectilinear podium that contains commercial office space, a spa, a bar, and a restaurant. There are 200 residential units, ranging in size from 900-square-foot one-bedrooms to 5,000-square-foot penthouses. The units’ interior drywall is left raw, ready for a boutique decorator’s touch, and the interior spaces are bathed in light from floor-to-ceiling windows.

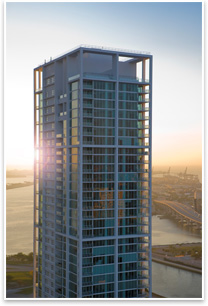

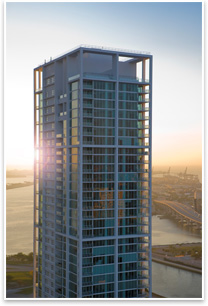

The east-facing tower is placed on a narrow site that it only 80 feet wide through the tower section, and the ocean view double-height units on this side are 20 feet across. To fit four dual-level units across one side on this face of the building, Oppenheim designed each unit’s upper and lower floor to interlock with each other, so that the middle units are entered from one level and the outer units are entered from a different level. This offset pattern is plainly visible on the east façade, where the middle units’ balconies are aligned, while the outer unit balconies align at a different level. On the west façade, the units are all single-level and are all aligned along one plane-height per floor, plainly expressed in the façade as well. “The building is derived as almost two towers that are combined,” Oppenheim says.

Ten Museum Park’s signature feature is its white concrete exoskeleton. Though seemingly light and delicate, the grid pattern helps to carry the building’s structural loads, and breaks up the monotony of the building’s façade rhythm—a monotony that buildings like Mies’s 860-880 Lake Shore Drive embrace. “We wanted to distort the typology of the residential tower,” Oppenheim says. “It starts to break down the scale of the tower [and] give it a certain abstraction.” Ten Museum Park’s signature feature is its white concrete exoskeleton. Though seemingly light and delicate, the grid pattern helps to carry the building’s structural loads, and breaks up the monotony of the building’s façade rhythm—a monotony that buildings like Mies’s 860-880 Lake Shore Drive embrace. “We wanted to distort the typology of the residential tower,” Oppenheim says. “It starts to break down the scale of the tower [and] give it a certain abstraction.”

This gridded concrete frame best illustrates where the building places itself between the opposing poles of classic Modernism and luxury bourgeoisie adornment. It’s superfluous to the primary volume of the building: graceful, chic, and yet still fundamentally structural.

And here’s a bit more Modernist flag waving from Ten Museum Park: It, like the vast majority of OPPENheim Architecture + Design’s work, uses the cube as the fundamental unit of design. “We’re always looking for ways to find the simplest methodology to build a particular project,” Oppenheim says. “We do see these as somewhat straightforward volumetrics, but then how we organize them and how we arrange them—that’s where the poetics happen.”

Form following experience Form following experience

Ten Museum Park is packed with luxe amenities, like a spa, 12 swimming pools, and rooftop and podium “pleasure gardens,” as Oppenheim calls them, that blur the division between inside and outside with daybeds and outdoor furniture; not to mention the views across the ocean and across Miami. These alone make one aware that OPPENheim Architecture + Design, indelibly grounded and based in Miami, is focused on rich, sumptuous, experientially derived architecture.

“I think architecture has gotten kind of carried away in terms of aggressive studies of form, where it almost supersedes the experience,” Oppenheim says. “We’re trying to actually deal with experience and have the form create that experience. [The building] becomes a vessel to absorb this beauty.” |

Two towers, two sensibilities

Two towers, two sensibilities

Form following experience

Form following experience