DC’s Kreeger Museum Showcases Philip Johnson’s Later Works DC’s Kreeger Museum Showcases Philip Johnson’s Later Works

by Russell Boniface

Associate Editor

How do you . . . honor the late work of a prodigious 20th century architect?

Summary: The Kreeger Museum in Washington, D.C., currently is holding an exhibition called “Philip Johnson: Architecture as Art,” which showcases the relationship between art and architecture as seen by Philip Johnson in his late works. Johnson also designed The Kreeger Museum, the private, nonprofit museum located in the former residence of Carmen and David Kreeger that holds their collection of 19th- and 20th-century painting, sculpture, and African art. The exhibition was curated by Hilary Lewis, a Philip Johnson scholar, and designed by New York-based Wendy Evans Joseph Architecture. Summary: The Kreeger Museum in Washington, D.C., currently is holding an exhibition called “Philip Johnson: Architecture as Art,” which showcases the relationship between art and architecture as seen by Philip Johnson in his late works. Johnson also designed The Kreeger Museum, the private, nonprofit museum located in the former residence of Carmen and David Kreeger that holds their collection of 19th- and 20th-century painting, sculpture, and African art. The exhibition was curated by Hilary Lewis, a Philip Johnson scholar, and designed by New York-based Wendy Evans Joseph Architecture.

A combination of models, drawings, sculpture, and photographs at the exhibition highlight the later works of Philip Johnson. “This exhibition was curated by Hilary Lewis, a Philip Johnson scholar who knew him for many years and collaborated with him on books towards the end of his life,” says Erich Keel, head of education at The Kreeger Museum. “She tries to show us his accomplishments at the last 10-12 years of his career, including models and a few realized projects. According to her theory, during those years he tried to break away from his Miesian concept or his Postmodernist interest, for example his Sony Building in New York City. This exhibition proposes three ideas. One is what she calls structured warp, which was Johnson getting away from straight lines and incorporating concepts of sculptor Frank Stellar, whose works Johnson collected. The second thing is what Johnson himself called Playing with Plato—colliding forms, applying color, and arranging structures. Third is his inspiration from the sculpture of artist John Chamberlain, known for twisting and fusing metal.” A combination of models, drawings, sculpture, and photographs at the exhibition highlight the later works of Philip Johnson. “This exhibition was curated by Hilary Lewis, a Philip Johnson scholar who knew him for many years and collaborated with him on books towards the end of his life,” says Erich Keel, head of education at The Kreeger Museum. “She tries to show us his accomplishments at the last 10-12 years of his career, including models and a few realized projects. According to her theory, during those years he tried to break away from his Miesian concept or his Postmodernist interest, for example his Sony Building in New York City. This exhibition proposes three ideas. One is what she calls structured warp, which was Johnson getting away from straight lines and incorporating concepts of sculptor Frank Stellar, whose works Johnson collected. The second thing is what Johnson himself called Playing with Plato—colliding forms, applying color, and arranging structures. Third is his inspiration from the sculpture of artist John Chamberlain, known for twisting and fusing metal.”

Johnson explores shapes Johnson explores shapes

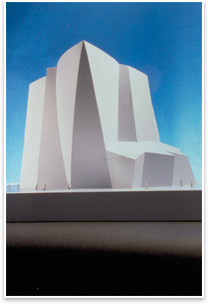

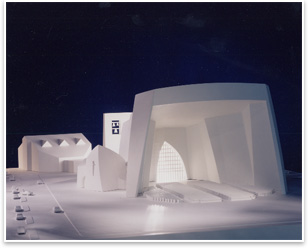

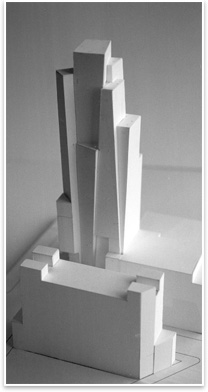

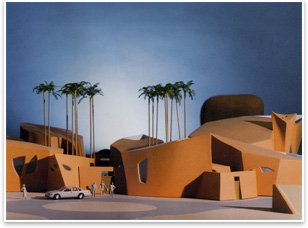

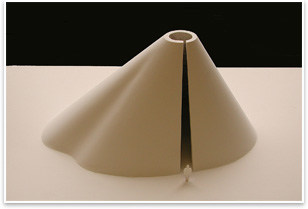

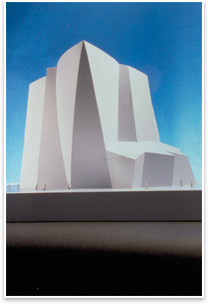

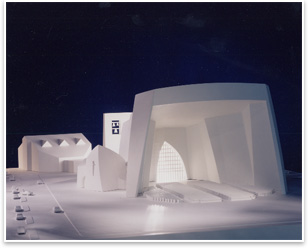

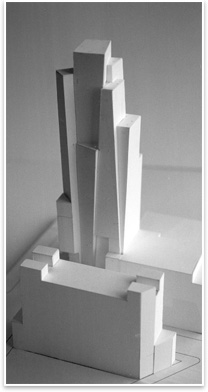

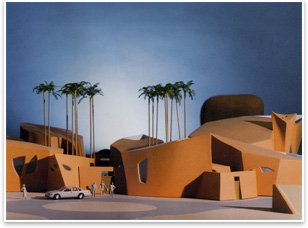

Johnson and his firm, Philip Johnson/Alan Ritchie Architects, based in New York City, produced work in the 1990s and 2000s that was often sculpture itself, Keel explains, utilizing various shapes and forms. Johnson produced numerous designs that are still in process at Philip Johnson/Alan Ritchie Architects. The exhibition features models of these project, which include the Cathedral of Hope for Dallas, which employs a series of warped forms; the Habitable Sculpture, which was a Soho residential tower designed for Antonio Nino Vendome that uses inclined façade shapes not perpendicular to the ground (“Each apartment would have a different layout,” Keel says); Oasis House, an ecological village in Negev, Israel, that features shapes that protect from sandstorms; and the Guadalajara Children’s Museum in Guadalajara, Mexico, highlighted by a solid pyramid and spirals. Johnson's gatehouse design, Da Monsta in New Canaan, Conn., is also on display. The Cathedral of Hope in Dallas, under way at Philip Johnson/Alan Ritchie Architects, expands Johnson’s earlier ideas of Da Monsta. Johnson himself designed the Kreeger Museum building when it was a residence of Carmen and David Kreeger. “David Kreeger was after him,” says Keel. “It was one of Johnson’s last residential buildings.”

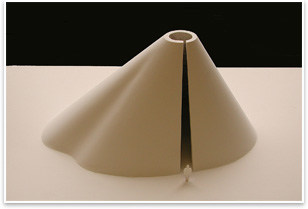

Keel explains that Johnson attempted to make his own architecture out of Stella’s sculptural concept of curves, beginning with an office project in Berlin in 1993. “They rejected it and wanted something Neo-classical 19th century,” says Keel. While Johnson’s “Berlin Fantasy” never came to fruition due to local zoning, Johnson’s Da Monsta gatehouse on his property in New Canaan, which sits in front of his Glass House, gave him a chance to experiment with these forms. “On this pavilion, everything is slanted, curved, and has no straight lines, especially if you look at the doors,” Keel points out. Keel explains that Johnson attempted to make his own architecture out of Stella’s sculptural concept of curves, beginning with an office project in Berlin in 1993. “They rejected it and wanted something Neo-classical 19th century,” says Keel. While Johnson’s “Berlin Fantasy” never came to fruition due to local zoning, Johnson’s Da Monsta gatehouse on his property in New Canaan, which sits in front of his Glass House, gave him a chance to experiment with these forms. “On this pavilion, everything is slanted, curved, and has no straight lines, especially if you look at the doors,” Keel points out.

“Johnson wanted to redefine Platonic shapes,” he continues. “Spirals, cylinders, cones … he could realize these irregular, non-Euclidean shapes. Johnson was obsessed with Plato and redoing the idea of the pyramid. Johnson looked at architecture much more in terms of art than as function of a shelter. In his last 12 years, Johnson had a lot of fun with architecture. He said he was returning to a second childhood and playing with shapes just like a child would, and I think he was fully aware of that. Children are allowed to be creative. I believe the Guadalajara Children’s Museum project, if it ever gets built, will be a wonderful testament to his creativity.” “Johnson wanted to redefine Platonic shapes,” he continues. “Spirals, cylinders, cones … he could realize these irregular, non-Euclidean shapes. Johnson was obsessed with Plato and redoing the idea of the pyramid. Johnson looked at architecture much more in terms of art than as function of a shelter. In his last 12 years, Johnson had a lot of fun with architecture. He said he was returning to a second childhood and playing with shapes just like a child would, and I think he was fully aware of that. Children are allowed to be creative. I believe the Guadalajara Children’s Museum project, if it ever gets built, will be a wonderful testament to his creativity.”

Keel says that zoning for the Habitable Sculpture tower in the Soho district in New York City, designed by Johnson in 2000, made the project unworkable, just like in Berlin. Instead, Johnson’s Urban Glass House, smaller and more traditionally Modern, was built. “You wonder sometimes. One of Johnson’s great complaints is that the codes can inhibit the inspiration of architects.” A model of the Urban Glass House is also on display in the exhibit.

Johnson the conductor; his appreciation of change

“I think Johnson was a very restless person and could not stay for an idea for a long time,” notes Keel. “He had a very inquisitive mind and was eclectic. Some critics hold this against him, but I think it’s one of his greatest talents—the way he could roam the continents and pick up forms and shapes that have never been built. Johnson was a formgiver, but definitely knew how to use what was available, like a conductor who could use his own repertoire.”

Concludes Keel: “Johnson was like a prism—if you change the prism, you have different colors. A philosopher Johnson admired was Heraclitus, who said: ‘The only thing permanent is change.’ That was what Johnson believed.” Concludes Keel: “Johnson was like a prism—if you change the prism, you have different colors. A philosopher Johnson admired was Heraclitus, who said: ‘The only thing permanent is change.’ That was what Johnson believed.” |

DC’s Kreeger Museum Showcases Philip Johnson’s Later Works

DC’s Kreeger Museum Showcases Philip Johnson’s Later Works