| Universal Faith, Local Design The design principles of Fay Jones bring a multi-faith chapel to a Presbyterian college campus in Decatur, Ga.

Summary: Julia Thompson Smith Chapel is a non-denominational, multi-faith religious space that generates its sense of spiritual reverence not through narrative and specific iconography, but through transcendent, experiential features. Heavily influenced by his former mentor Fay Jones, Maurice Jennings’ design for the chapel recalls Jones’ contextually humble approach to architecture.

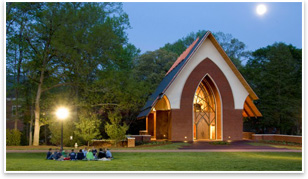

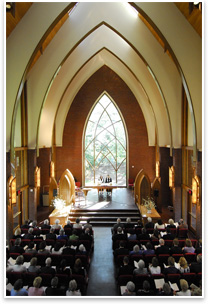

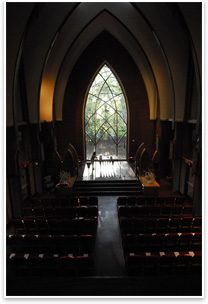

“The guiding principle, as Fay used to say, is to make a space where people can come and think their best thoughts, and sort of leave it at that,” says Walter Jennings, Assoc. AIA, the building’s project manager. Agnes Scott College is a small liberal arts women’s school in Decatur, Ga., a suburb of Atlanta. The 4,000-square-foot Julia Thompson Smith Chapel sits on a sloped quad, with walkout entryways at the lower level, where a small multi-faith meditation room is, and at the higher level, where the main sanctuary is. To be able to facilitate services for a wide range of faiths, neither of the rooms has permanently arranged pews or seating. The project began with a partnership between two of Jones’ primary disciples, Maurice Jennings, AIA, and David McKee, AIA. But, in 2006, while the building was still in preliminary design, McKee left the firm to begin his own firm and Jennings and his Fayetteville, Ark.-based practice completed the design. The chapel was dedicated on April 21 and is expected to open in May.

The arches that define the chapel’s interior space extend through the glass-walled north and south elevations out onto balconies as brick fins. The warm woods used in the interiors and the open arced spaces of the sanctuary enhance the chapel’s sense of spiritual reverence. Light from the skylights above and windows below make the white stucco-like gypsum that covers the interior arches glow. The chapel has no steeple, no crosses, and no crucifixes and instead opts for pleasingly abstract stained glass. Its fundamental Gothic vocabulary is perhaps its most formal religious reference. The Julia Thompson Smith Chapel does not become a sacred space by referring to religious narratives or specific iconography. All of its purely experiential features—the light; the open, arced space; the building’s implied skyward ascent—generate the chapel’s aura of peace and spiritual meditation.

Jones’ work has often been labeled Ozark Gothic or Contemporary Gothic, but this appropriation obscures key sensibilities that separate the grand-scaled, forceful imposition of awe of Gothic architecture and the humble contextualism and connection to nature of Jones’ Arkansas-based oeuvre. The Agnes Scott chapel does share the humble and reverent scale of Jones’ buildings. This body of work exists largely outside the late 20th-century debates that pitted Modernists vs. Postmodernists, Whites vs. Grays, and his best work could make these arguments seem superfluous and banal. A singular figure, Jones is hard to connect to any architectural narrative beyond the influence of Frank Lloyd Wright, with whom he studied and for whom he worked.

And, like Jones, the mastery of humbly scaled places of reverence brings its own quiet popularity. “We get asked to do what we’re known for,” says Walter Jennings. |

||

Copyright 2008 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› An Everywhere Space for Everyone’s Religion

› Thorncrown Chapel Receives AIA Twenty-five Year Award

› A Tribute to a Great Architect: E. Fay Jones, FAIA

Visit Maurice Jennings Architect Web site.

Read about Maurice Jennings architecture endowment at the University of Arkansas

Read sections of Robert Ivy’s, FAIA, book about Fay Jones.

Photos courtesy of Maurice Jennings Architects. Photo 3 is © Gary W. Meek Photography.