An Everywhere Space for Everyone’s Religion

Interfaith chapel finds common ground that can go anywhere.

by Zach Mortice

Assistant Editor

Summary: Andrew Liles’ design for an interfaith chapel is a small, self-contained portable and adaptable space. Its design coherence hints at the commonality of all religions.

The

goal of Andrew Liles', AIA, LEED-AP, design for an interfaith chapel

is to create an atmosphere of reverence and spirituality for people

of all faiths without any particular religion’s iconography

or mythology. Liles, who practices with the Jackson, Miss.-based

firm Canizaro Cawthon Davis, looks to form and fluid siting to express

overarching spiritual themes common to many faiths: the unity and

community of believers and the ubiquity of deity and faith. The

goal of Andrew Liles', AIA, LEED-AP, design for an interfaith chapel

is to create an atmosphere of reverence and spirituality for people

of all faiths without any particular religion’s iconography

or mythology. Liles, who practices with the Jackson, Miss.-based

firm Canizaro Cawthon Davis, looks to form and fluid siting to express

overarching spiritual themes common to many faiths: the unity and

community of believers and the ubiquity of deity and faith.

One and many

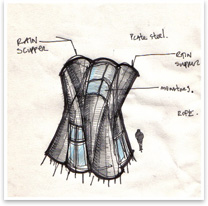

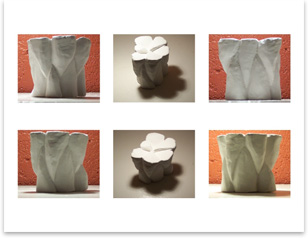

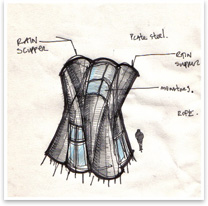

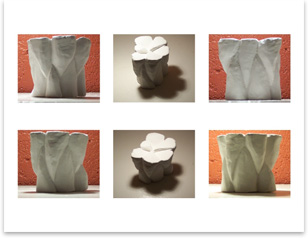

Liles’ design is starkly organic, with exterior welded plates wrapping into each other like intertwined vines or stems. Christianity is laden with vine metaphors, and Liles says he also thought of the form as fingers intertwined in prayer or meditation, or the strands of a rope coming together to form a whole stronger than the sum of its parts. “When you put the exact same things together, they actually assume a stronger property,” Liles says.

And so do people. By illustrating this principle on the façade of his chapel, Liles calls believers in to worship with the bedrock idea that uniting a community through belief makes it infinitely stronger. And so do people. By illustrating this principle on the façade of his chapel, Liles calls believers in to worship with the bedrock idea that uniting a community through belief makes it infinitely stronger.

Everywhere and nowhere

The most unique feature of Liles’ design is its total portability. Roughly 33 feet wide and 25 feet tall, it’s self-contained and compact enough to be transported by helicopter and ferried from place to place. Liles has no specific goals for its travels. It’s meant to go “nowhere in particular and pretty much everywhere”—a reminder of the omnipresence of religious faith. But this mobility allows it to be a window from one religion and culture into other religions and cultures.

As both a document of faith and a blank canvas, the interior of the chapel is lined with cork so that pictures, tapestries, and other religious art can be temporarily hung, depending on the user of the moment. “It’s like finding different layers of wallpaper on an old house,” says Liles. The floor plan of the chapel is equally malleable. An all purpose altar or pedestal (which can accommodate religious services with water, earth, and fire) is the center point of the circular floor divided into triads. A constellation of plug-in seating (stools and chairs are stored in the walls) allows for a variety of seating configurations. Any number of worshipers can sit in pairs or groups, facing each other, the outside, or in a crowd outside the chapel when all the doors are opened. Monotheistic religions with a specific worship leader (like Islam, Christianity, or Judaism) can place worshippers on two sides of the triad, leaving the third space as the stage for the leader. Religions with less emphasis on group-worship (like Buddhism or Shinto) can meditate or worship alone. The exterior is unfinished steel, meant to accept and record the wear markings of time and use. As both a document of faith and a blank canvas, the interior of the chapel is lined with cork so that pictures, tapestries, and other religious art can be temporarily hung, depending on the user of the moment. “It’s like finding different layers of wallpaper on an old house,” says Liles. The floor plan of the chapel is equally malleable. An all purpose altar or pedestal (which can accommodate religious services with water, earth, and fire) is the center point of the circular floor divided into triads. A constellation of plug-in seating (stools and chairs are stored in the walls) allows for a variety of seating configurations. Any number of worshipers can sit in pairs or groups, facing each other, the outside, or in a crowd outside the chapel when all the doors are opened. Monotheistic religions with a specific worship leader (like Islam, Christianity, or Judaism) can place worshippers on two sides of the triad, leaving the third space as the stage for the leader. Religions with less emphasis on group-worship (like Buddhism or Shinto) can meditate or worship alone. The exterior is unfinished steel, meant to accept and record the wear markings of time and use.

LED monitors line the exterior of the chapel, showing passersby what is going on inside. This emphasis on exposition and circulation make the chapel outwardly didactic, encouraging a progressive, accepting view of religion without factionalism and strife.

The lifecycle The lifecycle

Liles originally created this design for a competition hosted by the United Religion Initiative, a nonprofit organization that promotes interfaith dialogue and cooperation. A “subliminal” influence, Liles says, on his design’s sculpted curves is the work of Robert Bruno, a Texas architectural sculptor and artist. His welded, labryinthian steel spaces are both organic with streamlined carapaces and mechanistic in their rough-hewn density—the apotheosis of Liles’ design sensibility with the chapel.

The design began with Liles making a chart that compared the world’s major religions and contrasted what they required from a worship space. Liles says the resulting coherence of the design is testament to the essential similarity of them all. “It’s interesting how little you need to change to make a bunch of different faiths able to use the same space,” he says. The design began with Liles making a chart that compared the world’s major religions and contrasted what they required from a worship space. Liles says the resulting coherence of the design is testament to the essential similarity of them all. “It’s interesting how little you need to change to make a bunch of different faiths able to use the same space,” he says.

The life cycle of the chapel itself is also recognizable to many religions. It drops down from the sky into the earth. It grows, evolves, and changes in response to the people and things around it. It then is plucked up to the heavens again, to be reborn in a new life.

|