Shangri La Emerges Again . . . in East Texas

Lake|Flato creates LEED Platinum oasis

by Heather Livingston

Contributing Editor

Summary: In James Hilton’s 1933 novel Lost Horizon, Shangri-La is a mystical and harmonious valley, but most people think of Shangri-La as an Eden of the Orient: a place where all things exist in an aura of innocence, beauty, and the exotic. In eastern Texas, Shangri La exists again, this time transforming from the ashes of a ruined ornamental garden and a dying lake into a vast nature preserve and botanical garden. Summary: In James Hilton’s 1933 novel Lost Horizon, Shangri-La is a mystical and harmonious valley, but most people think of Shangri-La as an Eden of the Orient: a place where all things exist in an aura of innocence, beauty, and the exotic. In eastern Texas, Shangri La exists again, this time transforming from the ashes of a ruined ornamental garden and a dying lake into a vast nature preserve and botanical garden.

In Orange, Tex., near the border of Louisiana, sits the 250-acre Shangri La Botanical Gardens and Nature Preserve. Created in 1937 by philanthropist Lutcher Stark, Shangri La was once a glorious azalea garden situated adjacent a cypress/tupelo swamp. In the middle of the 20th century, its beauty was so well known that thousands of visitors descended on Orange every year to see the gardens, and every major gardening magazine published photographs of it. In 1958, a major snowstorm struck eastern Texas and destroyed the gardens and its thousands of azaleas. Shangri La remained closed for 40 years. In 2002, the Nelda C. and H. J. Lutcher Stark Foundation decided to rebuild the garden to its original splendor.

To fulfill its vision, the Stark Foundation engaged landscape architects Jeffrey Carbo, in Alexandria, La., and MESA Design Group, in Dallas, to construct ornamental gardens and a vast nature preserve that would restore the wetlands that were diminished when Stark created the lake. For the visitor center and education and research facilities, Carbo and MESA recommended Lake|Flato Architects. To fulfill its vision, the Stark Foundation engaged landscape architects Jeffrey Carbo, in Alexandria, La., and MESA Design Group, in Dallas, to construct ornamental gardens and a vast nature preserve that would restore the wetlands that were diminished when Stark created the lake. For the visitor center and education and research facilities, Carbo and MESA recommended Lake|Flato Architects.

Restoring the wetlands

Says Ted Flato, FAIA, principal, Lake|Flato Architects: “We saw it as an opportunity not just to build buildings that were sustainable, but to use the buildings to amend or fix the landscape.” One of the first challenges encountered was to repair the lake. Because it had been separated from its natural systems, its natural flushing through the wetlands was eliminated, leaving it a stagnant, anaerobic lake.

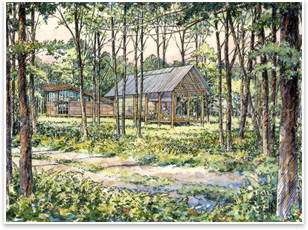

With Landscape Architects MESA Design and Carbo, “we created wetlands that are a series of flushing pools that polish and clean the water for the lake,” Flato says. “Then, around those wetland cleansing ponds is a series of visitor education buildings that, as much as possible, have exterior circulation that allows the patron to have as close a connection to the landscape and the outdoors as possible.”

Designing a village of nature

Flato says that they created a village of sorts around the wetland cleansing ponds. Included in the list of village structures are greenhouses for educational purposes and ornamental garden plant propagation, a bookstore, a café, staff offices, a small theater, a museum, and other utilitarian buildings. Flato notes that there already existed on the site three greenhouses, one from the turn of the century and two from the 1930s. “They were all lined up like greenhouses often are, so we [used that as inspiration for the village],” he says. “We wanted to build the majority of the new buildings near where visitors park to take up as little land of the natural area as possible, so we incorporated the greenhouses in the overall complex. In fact, the design vocabulary came from those greenhouses.”

The existing greenhouses had a brick base and were steel and glass, so all of the buildings in this first complex are of that nature, explains Flato. “They’re either built with recycled brick from an old warehouse in the south, or they’re light steel and glass. The buildings almost have a sense that they’re like greenhouses, so they have a very utilitarian quality to them, which worked well for what we were trying to do, which was to have simple shapes that would collect water and incorporate solar collectors.” The buildings have light glass that sits on heavy brick, allowing the shed-shaped buildings with high operable windows to take advantage of the prevailing breeze. The one-room-wide structures facilitate cross ventilation so that the buildings use as little energy as possible, but they also maintain a strong connection to the outdoors by having as much natural circulation as possible. “The buildings almost feel like utilitarian buildings that are there to work with the land,” explains Flato. The existing greenhouses had a brick base and were steel and glass, so all of the buildings in this first complex are of that nature, explains Flato. “They’re either built with recycled brick from an old warehouse in the south, or they’re light steel and glass. The buildings almost have a sense that they’re like greenhouses, so they have a very utilitarian quality to them, which worked well for what we were trying to do, which was to have simple shapes that would collect water and incorporate solar collectors.” The buildings have light glass that sits on heavy brick, allowing the shed-shaped buildings with high operable windows to take advantage of the prevailing breeze. The one-room-wide structures facilitate cross ventilation so that the buildings use as little energy as possible, but they also maintain a strong connection to the outdoors by having as much natural circulation as possible. “The buildings almost feel like utilitarian buildings that are there to work with the land,” explains Flato.

Making the most of a bad situation

Further out into the preserve are outdoor classrooms that are completely off the grid and, in some cases, constructed of fallen trees from Hurricane Rita. “We capitalized on the fact that we had a bunch of fallen trees,” the architect says. “We recycled those trees and used them in some of our buildings and for furniture.” Wherever possible, rough hewn elements were milled on-site to save transportation costs and environmental impact, while fine millwork for furniture was milled elsewhere.

Opened to the public on March 11, the new, LEED® Platinum-certified Shangri La has a mission to “mentor children of all ages to be kind to their world.” To do so, it offers formal botanical gardens with more than 300 plant species and a nature center with a cypress/tupelo swamp, outdoor classrooms, laboratory, and more, which will allow visitors to learn about the natural world in general and the unique local ecosystem in particular. Opened to the public on March 11, the new, LEED® Platinum-certified Shangri La has a mission to “mentor children of all ages to be kind to their world.” To do so, it offers formal botanical gardens with more than 300 plant species and a nature center with a cypress/tupelo swamp, outdoor classrooms, laboratory, and more, which will allow visitors to learn about the natural world in general and the unique local ecosystem in particular.

“I think for me,” says Flato, “[the most interesting aspect of the project] was the opportunity to repair the lake and augment the natural areas. The fun challenge was developing buildings that worked closely with the landscape. You have these very orderly buildings when you first come in that are all about machines fixing the land, polishing water, creating wetlands … and then very different types of structures that are built of the materials that we had on site that are floating above these wetlands. It was a great deal of fun to create these two different vocabularies that made sense and encouraged you to go out into the landscape.” |