“Living” Building Steps Lightly to Give Back to Nature

Schaar’s Bluff goes beyond LEED to heal the landscape

by Heather Livingston

Contributing Editor

How do you . . . design a building that gives more than it takes from the natural landscape? How do you . . . design a building that gives more than it takes from the natural landscape?

Summary: “Design the first building for the next generation.” This was the charge given to Meyer, Scherer & Rockcastle Ltd. (MS&R) by its client, Dakota County, Minn. Set to open to the public this spring, the Gathering Center at Schaar’s Bluff goes beyond LEED® certification in its effort to create a building for the future. The gathering center is based on the idea of permaculture: designing ecological, efficient buildings that focus on sustainable use of local resources and energy, with the ultimate goal being to give back to nature. Sean Wagner, AIA, LEED-AP, director of sustainable design for MS&R elaborates: “Permaculture is assessing the natural energies within the site itself, and then understanding how we as human beings begin to impact that: how soils lead to plants, plants lead to food, and how occupying that space with human habitation begins to impact or interrupt those natural balances and cycles.”

The site The site

Located at the Spring Lake Reserve in Nininger Township, Schaar’s Bluff has an extraordinary history. While most historic sites in the United States date back a mere few hundred years, Schaar’s Bluff is one of the precious few where archaeologists have traced 8,000 years of continuous human habitation. Advantageously located on a bluff overlooking the Mississippi River, the county park has long been a favorite with locals and tourists. But, says Wagner, the site had last received serious attention in the late 1960s or early ’70s. “It had the traditional playground equipment with parking lots, mowed grass, crabapple trees, and open space, but it didn’t respect the nature of the site,” he explains. Wagner also notes that an unusable “asphalt no-man’s land” existed between the park reserve and a grouping of old-growth woods that sit along the bluff top.

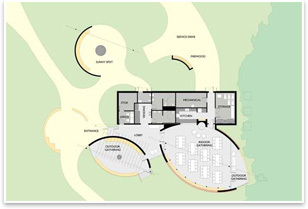

The design of the new 3,500-square-foot Gathering Center, so named for its long history as a local gathering place, is a reflection of the past, present, and future of the site. The building’s shape mimics an irregular circle around a campfire ring and its simple forms allude to indigenous structures and the importance of the compass points. Windows open the building to the sun in the south while carefully framed west-facing views provide a constant connection to the river. “The building is as dramatic as the site,” says Thomas Meyer, FAIA, principal in charge. “People have lived on this land for over 8,000 years, and now we’re building something new that honors the site’s history while responding to and sustaining the surrounding environment for the future.”

“If this building was only about sustainability, it would be different,” continues Meyer. “We could have simply tacked on a solar panel or designed a green roof, but this building is also about history and, at its core, it is about gathering. Consequently, the design tries to resolve the conflicts among technology, nature, and history.” “If this building was only about sustainability, it would be different,” continues Meyer. “We could have simply tacked on a solar panel or designed a green roof, but this building is also about history and, at its core, it is about gathering. Consequently, the design tries to resolve the conflicts among technology, nature, and history.”

Beyond LEED

However, a great portion of the design is devoted to ensuring sustainability. The gathering center was carefully sited to take full advantage of the microclimate. An on-site wind turbine will generate more than 90 percent of the building’s annual electrical load, with any excess power returned to the electrical grid. Operable windows located on opposite sides of the building and linked to the HVAC systems allow breezes to cool or warm the building throughout the seasons. The high performance building envelope is designed to control heat gains and losses by using super insulation techniques, automated and fixed shading devices, and light/heat sensor-controlled window blinds. In-floor radiant heat keeps the building above 54 degrees in winter, a comfortable temperature given the short amount of time people average at the trailhead. A high-efficiency air-to-air heat exchanger will also capture energy in ventilation air. Sensors located throughout the interior interactively monitor lights, HVAC, window shades, and ventilation. MS&R calls the building “alive” because of its ability to respond to changing weather conditions to conserve energy.

To maximize potable-water conservation, rainwater is captured on the roof and used to flush toilets. The resultant waste water is then treated in an on-site septic system before recharging the aquifer. Wood used during the gathering center’s construction was locally harvested and FSC-certified. Finally, adding to its moniker as a living building, a trellis with fruit-bearing vines will run alongside the structure to provide shade and sustenance to wildlife. To maximize potable-water conservation, rainwater is captured on the roof and used to flush toilets. The resultant waste water is then treated in an on-site septic system before recharging the aquifer. Wood used during the gathering center’s construction was locally harvested and FSC-certified. Finally, adding to its moniker as a living building, a trellis with fruit-bearing vines will run alongside the structure to provide shade and sustenance to wildlife.

Into the urban realm

Wagner notes that although Schaar’s Bluff is a special and unique site, the ideals of permaculture are as applicable in a dense, urban setting. “The natural world continues to exist even in urban environments, and what we are beginning to explore and trying to strive for is a better relationship between the built and natural worlds,” he explains. “Part of that comes from developing opportunities for human connection between occupants of buildings and the natural environment. There’s a whole realm of personal and emotional connections that we need to explore to make the true transformation to a carbon neutral environment. We can mandate and regulate carbon neutrality, but until it becomes meaningful to people in a personal, emotional, or ethical way that mandate is hollow.” |