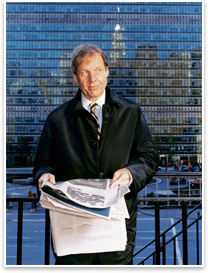

Theodore

H.M. Prudon, PhD, FAIA Theodore

H.M. Prudon, PhD, FAIA

Summary: Theo Prudon is a Dutch-born architect and principal of Prudon & Partners, a firm specializing in restoration. As the founding president of DoCoMoMo/US (The Documentation and Conservation of Buildings, Sites, and Neighborhoods of the Modern Movement), Prudon leads the U.S. chapter of the international organization dedicated to preserving Modernist structures. Prudon also is a DoCoMoMo International board member and an adjunct associate professor of historic preservation at Columbia University. Education: I have a master’s degree in architecture from the Delft University of Technology in Holland, a master’s of science in architecture from Columbia University, and a PhD in architecture from Columbia. Interest in preservation of Modern structures: I went through the preservation program at Columbia and have been teaching in the program for 30-some years. I was always trained as a Modern architect, and, over time, the two interests combined, looking at more contemporary architecture. I also am the president of an organization called DoCoMoMo/US, which is a part of an international organization that has representation in 54 countries and was founded in the Netherlands, which is where I was born and educated. The public and Modernism: I think that over the last decade there’s been a significant shift to recognition that heritage over a more recent period is important. In general terms, I think the larger public still has some qualms about appreciating how significant it is. In the architecture community an appreciation of this heritage is pretty clear, but in the larger general community there are still cases where people ask: Why is this historic? Or why is it beautiful? But I think that there’s no question that attitudes have significantly changed. DoCoMoMo membership: DoCoMoMo has probably about 400-500 members. What’s great about DoCoMoMo is that it’s a mixture of architects, general public, and the academic community. I think on that it’s unique as compared to some other preservation organizations. DoCoMoMo’s challenges: The particular challenges are fourfold:

The greatest Modernist loss: I think what lots of people have begun to focus on is the loss and potential loss of post-WWII single-family residences that are in prime locations and are, in contemporary terms, not large enough or comfortable enough for whatever reasons. We’ve lost many of them, and it’s only now, slowly, beginning to turn a little bit. The people in the real-estate community are beginning to market these buildings as unique; more as artifacts than as significant buildings. I think a fair amount was lost 10 to 15 years ago. AIA and DoCoMoMo: The affiliations are first, in the Historic Resources Committee (HRC) and secondly, mostly through the local membership. On a national level, there are no formal relationships, but I think that there are a number of prominent and senior members with the AIA community who are members of us and are also active on our board. Because we are a national organization that’s organized in chapters across the country, a lot of the cooperation between the AIA and DoCoMoMo takes place on that level. Architects’ responsibility in preserving Modern architecture: Firstly, architects should talk to more people and explain to them why the buildings are important. Secondly, where they are charged with the responsibility of working on such a building, they should be very conscious as to the unique requirements of such a building and also explain that clearly to the surrounding communities and their clients. The situation that we always run into is people telling us that buildings are obsolete. It’s a scale issue. If you are preserving a two-story brick house in Virginia from 1755, the pressures on it are different than if you’re talking about a 20-story building in a downtown location that is a significant architectural piece of work. So, the acceptance of the 18th century building, both because of its rarity and because of its small scale, is a lot easier than a building that is much taller or bigger. Yes, the programmatic requirements have changed, but they will always change, so therefore the creative interpretation of that becomes much more significant. Thirdly is the durability issue. I think some of that can be resolved technically and should not be a reason to reject a building out of hand. Changes do take place. I think that for us, we have a tendency to focus on something and say: “Look, we can’t use it anymore.” But the reality is that what we think is significant today or the program that we want today will be very different five years from now. The changes are very rapid, and so we’ve got to be very conservative, modest maybe in how we approach these things. Structures at risk presently: There are a lot of them. I would hate to single one out. There is the Boston City Hall on the one hand. There is the Neutra building in Gettysburg [the Cyclorama] on the other hand. There’s Riverview High School in Florida, which is a Rudolph building. It’s on all levels and in all building types. Reading material: I have just finished the galleys of my own book. The book is called Preservation of Modern Architecture. It deals very much with the subject and is being published by John Wiley in April of this year. I just finished the galleys, and so now I can read the work of others again. What I’m reading now is by Bill Addis and it’s called Building: 3,000 Years of Design, Engineering and Construction. It’s probably three inches thick, but it’s interesting. It’s written by a UK engineer and has interesting analysis of building over the last century. What’s interesting about it—which is something I always feel is missing in the teaching of preservation—is that it looks at the actual building process. We talk about the aesthetics and we talk about whether or not it’s a particular style, but what’s interesting is the whole building process—particularly for Modern architecture, since that process has so significantly changed since the middle part of the 19th century as a result of the Industrial Revolution. |

||

Copyright 2008 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

thoughts and theory

big buildings

smaller scale

special issues

recent related

› WMF Launches Prize to Honor Modernist Preservation

› Los Angeles Business Council Honors City’s Best Architecture

The bi-annual DoCoMoMo International conference will be held in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, from September 17–19. For more information, visit the DoCoMoMo Web site or the conference Web site.