| Arboretum Visitor Center Stands Tall—Against the Yardstick of a Tree Now LEED Platinum certified, the Bernheim Arboretum Visitor Center integrates the natural and the artificial

Summary: The Bernheim Arboretum Visitor Center in Clermont, Ky., is a highly sustainable facility that self-consciously and transparently models its green features after the ecological balance a tree maintains with its environment, such as producing oxygen, deriving its energy from sunlight, and itself becoming a habitat for nature. The William McDonough + Partners-designed building is made of recycled wood constructed into a series of trellises and pergolas that provides a framework to bring people into closer contact with nature. William McDonough + Partners’ Bernheim Arboretum Visitor Center in Clermont, Ky., sits in between two noble conceptual orientations: to be a building that works like a tree and a building that explains its sustainability processes like a teacher. These goals were less an instance of formal mimicry and more an issue of building performance. The point, says McDonough’s Kevin Burke, AIA, was to ask “How productive are our buildings if we were to measure them against something like a tree?” So how “productive” is it? The United States Green Building Council granted LEED® Platinum certification to the visitors’ center—the only building in Kentucky, Tennessee, Indiana, West Virginia, and Virginia to attain this level of certification. Charlottesville, Va.-based McDonough + Partners, an industry-wide leader in sustainable design, explored the building as a tree and as a teacher motif previously in their Oberlin Environmental Studies Center in Oberlin, Ohio. The architect of record for the Bernheim project was Barnette Bagley Architects of Lexington, Ky.

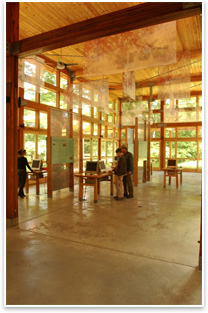

The most apparent sustainable feature is the building’s heavy reliance on recycled wood. It’s assembled mainly from pickle vats and bourbon rackhouse lumber. Completed in 2005, the 6,000-square-foot visitor’s center is constructed as a series of trellises and pergolas that extend out from wood-framed window walls—light, warm, and a constructive intrusion on the natural landscape. All the natural light coming through the expansive glazing makes the wood glow with an inviting golden hue, part rustic cabin and part contemporary architecture. Like a tree, the trellises themselves can become a natural habitat and a meeting place for the natural and the artificial. “The trellis becomes a sort of wrap-around shade-structure as the plants and nature grow on it,” says Burke.

“The visitor center helps set the stage for storytelling about sustainability, and great stories are the bedrock of meaningful education,” says Claude Stephens, Bernheim’s education director. “The project helps illuminate the spiritual, biological, and economic advantages of living in agreement with nature.” The Bernheim Arboretum Visitor Center sits in a 14,000-acre arboretum south of Louisville that was designed by Frederick Law Olmsted in the 1930s. Established by a German immigrant who rose to prominence through the whiskey-distilling business, the arboretum didn’t open to the public until 1950. It contains flexible exhibit space, a lobby, a shop, and a café that extends outside in good weather. Cost vs. value |

||

Copyright 2008 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Kudos Abound in the Bluegrass State

› Daniel Boone Wilderness Road Interpretative Center Blazes Forward

› Growing Green at Conservatory, Botanical Garden Welcome Center

› Santa Monica Part First to Receive LEED Silver Rating

Link to Cradle to Cradle, Michael Braungart and William McDonough’s book on the transformation of industry through environmentally conscious design.

Visit William McDonough + Partners Web site.

Visit the Bernheim Arboretum Web site.

For information on offerings from the AIA Committee on the Environment, visit AIA.org.