7/2006

by Russell Boniface

Associate Editor

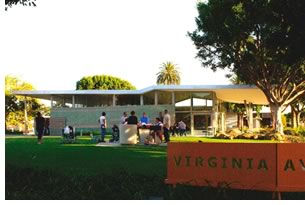

Virginia Avenue Park, located in the heart of Santa Monica, Calif., is the first park in the U.S. to be awarded the LEED® Silver Rating for environmental sustainability by the U.S. Green Building Council. Designed by Santa Monica, Calif.-based Koning Eizenberg Architecture and San Diego’s Spurlock Poirier Landscape Architects, Virginia Avenue Park is located in the heart of the Pico Neighborhood in western Los Angeles County.

Virginia Avenue Park, located in the heart of Santa Monica, Calif., is the first park in the U.S. to be awarded the LEED® Silver Rating for environmental sustainability by the U.S. Green Building Council. Designed by Santa Monica, Calif.-based Koning Eizenberg Architecture and San Diego’s Spurlock Poirier Landscape Architects, Virginia Avenue Park is located in the heart of the Pico Neighborhood in western Los Angeles County.

A park that’s worth the wait

Virginia Avenue Park is a newly renovated, nine-acre urban neighborhood park that is highlighted by its use of sustainable strategies and features. Planning for the park began 15 years ago and, after three land acquisitions, hours of community meetings and public hearings, and numerous redesign changes by the architects, the $13-million construction project was completed and open for public use late last fall. During Virginia Avenue Park’s grand re-opening festival, city council member Kevin McKeown enthused that “patience has paid off.”

The input from the community was instrumental in the park’s redesign and one of the reasons it took so long to finish. But architects, community members, and city officials agree it was worth the wait. At the park’s unveiling, Santa Monica Parks Commissioner Neil Carrey called it “a community-designed park” because “it took a lot of input from a lot of people working together.”

Council member Herb Katz added: “This is probably one of the few parks that has had this much public input, and I’m really proud to see it.”

Council member Herb Katz added: “This is probably one of the few parks that has had this much public input, and I’m really proud to see it.”

A community-based park for the 21st century

Wide community input, led by the Virginia Avenue Park Advisory Board and the Virginia Avenue Park Working Group established by the Santa Monica Recreation & Parks Commission, informed the concept design process all along the way. Julie Eizenberg, AIA, president and principal-in-charge of Koning Eizenberg Architecture, says the project was community–based from the start. “The community wanted a park for a wide collection of recreational and educational activities, and their need for open space was extraordinary,” Eizenberg says. “But they also wanted a casual-use space—a place where children could gather to play pick-up soccer games, for example, not a place for the community to hold organized little league games. So, in response, we designed playing spaces that weren’t too large. There is always a design mind-set going into a project like this when you have an initial premise, but once a community gets involved, the rules change.”

A park committee was formed of architects, residents, and city representatives. “The program and its ongoing disposition grew out of those meetings,” Eizenberg explains. “It was a very well-structured process. The community felt included, not threatened. It was important to us that we involved both the people who would speak up loudly as well as those who didn’t speak up loudly. They all cared very much about the project and felt they belonged. Despite different opinions, it worked out better than you would have expected.”

Indeed. The collective input resulted in a redesigned, re-equipped, and enlarged park due to a new three-acre lawn expansion. The park now became 72 percent open area. In addition to three adaptive reuse buildings and one new building, there are picnic areas, two playgrounds, two basketball courts, handball and sand volleyball courts, a playing field for soccer or other game or sport, a tot-lot sand box, barbeque facilities, walking paths, and a splash area called “The Beach Blanket.” Much of the park signage is adorned in bright orange and green-blue colors.

Indeed. The collective input resulted in a redesigned, re-equipped, and enlarged park due to a new three-acre lawn expansion. The park now became 72 percent open area. In addition to three adaptive reuse buildings and one new building, there are picnic areas, two playgrounds, two basketball courts, handball and sand volleyball courts, a playing field for soccer or other game or sport, a tot-lot sand box, barbeque facilities, walking paths, and a splash area called “The Beach Blanket.” Much of the park signage is adorned in bright orange and green-blue colors.

A park for the 21st century

It’s interesting to note, however, that its landscaping and sustainable features are not Virginia Avenue Park’s only state-of-the-art concepts. The park is now wired for the 21st century. Keeping up with the times, the park has Wi-Fi Internet access throughout, a state-of-the-art computer lab, and a recording studio. Even the two playgrounds have “space-age”-style equipment.

The park contains four buildings to house inside activities, offices, and infrastructure:

- Park Center, which houses the Santa Monica Police Department Substation, park administration offices, the Police Activities League, and two state-of-the-art fitness gyms—one with a boxing ring and weights

- The renovated 2101 Building, which contains a teen center

- A refurbished senior center called the Thelma Terry Building, which houses a multipurpose room and two classrooms

- The Patio, a new 1,300-square-foot building that houses park programs and mechanical equipment; the new building is consistent with the renovated buildings in its “folded roof” design, used as a repeated motif for shade structures or entrance canopies for each building.

A colorful new 80-foot by 24-foot mural on plexiglass panels called “Our Pico Neighborhood” is on the wall of the Park Center facing the street. It was painted by artists Wayne Healy and David Botello of East Los Streetscapers and contains images of the surrounding community. Park programs run a very wide gamut in response to the community’s support in areas of education, culture, health and recreation, and community resources, such as homework assistance.

A colorful new 80-foot by 24-foot mural on plexiglass panels called “Our Pico Neighborhood” is on the wall of the Park Center facing the street. It was painted by artists Wayne Healy and David Botello of East Los Streetscapers and contains images of the surrounding community. Park programs run a very wide gamut in response to the community’s support in areas of education, culture, health and recreation, and community resources, such as homework assistance.

Santa Monica embraces sustainability

Virginia Avenue Park is the first in the nation to receive a LEED Silver Rating. “That’s bizarre,” Eizenberg says in disbelief. “You would have thought that a park would have been awarded the LEED Silver rating before this.”

Sustainability wasn’t an issue at first among the residents, but about five years ago that changed, she explains. “They became interested in the idea, but they had to be made aware that a lot of sustainability is invisible and justifies strategies such as reusing construction material, having a permeable surface, creating a system that can replenish water, and replanting trees.” But the community came on board with the idea, and despite cost revisions, so was the City of Santa Monica. “Not long ago, if you proposed sustainability to a community, you would have been laughed at, but that has changed, and Santa Monica became encouraged to experiment. They thought it was worth it.”

Sherida Jeffrey, senior associate of San Diego-based Spurlock Poirier Landscape Architects, welcomed the opportunity to bring her landscape expertise to the project. Jeffrey worked with 2006 AIA Gold Medal recipient Antoine Predock, FAIA, on the landscaping for Petco Park, San Diego’s new downtown ballpark, and its adjacent “Park at the Park.” For Virginia Avenue Park, Jeffrey explains that it was important right off the bat to have in place a permeable surface with an onsite rain irrigation system to capture and replenish storm run-off. “Sustainability meant to not have the stormwater drain into the Pacific Ocean,” she says. “We recommended a permeable paver system, which for the City of Santa Monica was a new idea.

Sherida Jeffrey, senior associate of San Diego-based Spurlock Poirier Landscape Architects, welcomed the opportunity to bring her landscape expertise to the project. Jeffrey worked with 2006 AIA Gold Medal recipient Antoine Predock, FAIA, on the landscaping for Petco Park, San Diego’s new downtown ballpark, and its adjacent “Park at the Park.” For Virginia Avenue Park, Jeffrey explains that it was important right off the bat to have in place a permeable surface with an onsite rain irrigation system to capture and replenish storm run-off. “Sustainability meant to not have the stormwater drain into the Pacific Ocean,” she says. “We recommended a permeable paver system, which for the City of Santa Monica was a new idea.

“Different permeable pavers were used. For the lawn, we used a fiber matrix of 2-inch by 2-inch turf squares, similar to a golf course. We created infiltration trenches under the pavers to catch, drain, and replenish storm water, which prevents super compaction of pollutants at the root zone. We used a concrete block permeable paver for areas such as the parking lot and walkways. Voids in the corners of the paver were filled with an aggregate. For the different playground surfaces we used a sand and ground rubber tire infill, and for other walkways we used a resin pavement with soil. The only asphalt we used was for the drive aisles in the parking lot.”

Jeffrey points out those permeable pavers are advantageous because “you can play on it and you can park on it.” She mentions that promenade areas even act as fire access routes. The paver feature also comes in handy, she points out, when trying to save the local Saturday morning Farmer’s Market. “We created a surface area paved with decomposed granite that acts as a play space and picnic area, but on Saturday morning doubles for the Farmer’s Market and accommodates parking. The surface has a bare-dirt trail feeling but doesn’t get muddy, and there are is a sycamore tree planted for every three parking spots.”

Jeffrey points out those permeable pavers are advantageous because “you can play on it and you can park on it.” She mentions that promenade areas even act as fire access routes. The paver feature also comes in handy, she points out, when trying to save the local Saturday morning Farmer’s Market. “We created a surface area paved with decomposed granite that acts as a play space and picnic area, but on Saturday morning doubles for the Farmer’s Market and accommodates parking. The surface has a bare-dirt trail feeling but doesn’t get muddy, and there are is a sycamore tree planted for every three parking spots.”

Mixing the trees

The new sycamore trees also form a tree canopy throughout the park, and care was taken to relocate existing trees affected by construction. “Plus there is an aesthetic aspect to it,” Jeffrey notes. “It wouldn’t have looked too good to have all the older, larger trees on one side of the park, and all the new, smaller trees on the other side of the park, so it looks better to relocate the big ones and mix them with the new ones.” Colorful, indigenous, drought-tolerant plants—a.k.a., low-water plants—were incorporated into various garden areas.

Adaptive reuse of the park buildings included transforming a grocery store, a senior citizen center, and an old paint shop into three of the four park buildings. Construction materials such as concrete were recycled, and renewable paints, woods, and carpeting were used in the buildings. “The Beach Blanket,” a splash-water play area geared for young children is made of a permeable, wet-area, Laticrete paver with glass aggregate. A jet-spray timer system in the pavers is used for water conservation. “The splash pad has an orange and green-blue pattern that mimics a beach towel,” explains Jeffrey. “At night a fiber-optic light system illuminates the beach towel design. There are also little green water canons for the kids to play with to add to the fun. The children really enjoy it.”

Adaptive reuse of the park buildings included transforming a grocery store, a senior citizen center, and an old paint shop into three of the four park buildings. Construction materials such as concrete were recycled, and renewable paints, woods, and carpeting were used in the buildings. “The Beach Blanket,” a splash-water play area geared for young children is made of a permeable, wet-area, Laticrete paver with glass aggregate. A jet-spray timer system in the pavers is used for water conservation. “The splash pad has an orange and green-blue pattern that mimics a beach towel,” explains Jeffrey. “At night a fiber-optic light system illuminates the beach towel design. There are also little green water canons for the kids to play with to add to the fun. The children really enjoy it.”

It’s a hit!

Eizenberg agrees, adding that all age groups are enthusiastic about their new park. She describes a recent evening visit: “It was boppin’. The residents have really taken ownership. I saw an incredible cross-section of activities: pick-up soccer and basketball games, cheerleaders performing on each other’s shoulders, pool being played on a table in the courtyard, a hip-hop deejay, The Beach Blanket; in the park center, there was dancing, exercising, and boxing training. It’s cool over there!”

Advice? “Parks can take a lot of time to do,” Eizenberg says. “The investment of time and money takes a lot of preparation. But it’s not about control. Once a community feels included and not threatened, then it’s just a matter of getting all the ducks in a row. With Virginia Avenue Park, it was a combination of broad and flexible thinkers who took a lot of care and never lost sight of wanting the park to be the best it could be. It was well worth doing.”

Copyright 2006 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

The first six photos are © Marvin Rand. The last photo is © Jim Litzel.

![]()