|

Gwathmey Helps Yale Architecture School Icon

Re-emerge Alum returns to New Haven and retraces the steps of a mentor

Rudolph’s Yale Art and Architecture Building has been called a lot of things: a failed icon, a Modernist masterpiece, a symbol of institutional antipathy to creative life, an example of Modernism at its most aloof and formally extravagant, and the most important building by one of the mid-20th century’s most important architects. In a 1998 Yale Alumni Magazine article, Robert Stern, FAIA, who would later become the dean of Yale’s architecture school, called the building an attempt to synthesize and reconcile the conflicting strains of Modernism patterned after the work of Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, and Frank Lloyd Wright.

“The ultimate Modern building” In the 1950s and ’60s, the university (now arguably the nation’s premiere architecture school) was amassing an impressive stock of world-class architecture. Examples include Eero Saarinen’s Ingalls Rink, the Beinecke Library by Gordon Bunshaft, and, of course, Louis Kahn’s Yale University Art Gallery, which sits across the street from Rudolph’s site. “Even as the building was under construction, Rudolph made so many little changes to make the ultimate Modern building that could co-exist equally with Kahn,” says Gwathmey.

Some objected to the building as being too heroic or overbearing. With Kahn’s art gallery across the street, Gwathmey says the two buildings establish their own context beyond historicism and neighborhood sensibilities. Day to day, the art students who shared the building complained of being ghettoized, according to Yale Alumni Magazine, because art classrooms and studios were placed in the least favorable spaces in the facility. The building was also caught in a sharp shift in architectural tastes, away from abstract expressionist Modernist towards historicist Postmodernism. One particular Postmodernist was put in a position of great authority over the building in 1965, when Charles Moore became the dean of the architecture school.

Gwathmey uses the word “regime” when talking about Moore’s resentment of the building; an ironic choice that illustrates the polarization of the ‘60s, given that Moore, the playful Postmodernist, likely thought that Rudolph and his ilk were more aptly described as such. The rejection of the building, Gwathmey says, was both “philosophic” and a “change in the point of view about Modern architecture.” A fire in 1969 and subsequent insensitive repairs further blurred the line between politics and architecture and the building’s original intent and condition. When the smoke cleared, rumors were reported in the media that the fire was set by architecture students angry about the building, though investigators could never find proof of this, and the fire was ruled an accident. To repair the damage, Moore allowed the building to be broken up, with ad-hoc partitions obscuring Rudolph’s design. By 1988, Rudolph had disavowed the building, refusing to talk about it. “The building became, in a sense, a victim,” says Gwathmey. The turnaround

Art and architecture

Gwathmey calls this project “an inventive restoration,” and its intent is largely to clean away history and present the art and architecture school as it was originally intended. “You may love [Rudolph’s] work or you may hate his work, but it’s significant architecture,” says Cruickshank. If Gwathmey’s restorations succeed, students and visitors will get to place themselves along this continuum after seeing the building on its own merits for the first time in decades.

|

||

Copyright 2008 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

Recent related

› Sustainable Science

› Kahn’s Yale Center for British Art Receives Twenty-five Year Award

› UNM Albuquerque Gets New School of Arch and Planning

Photos:

1. Yale University Art & Architecture Building from the southeast, 1963.

Photograph © Ezra Stoller/Esto.

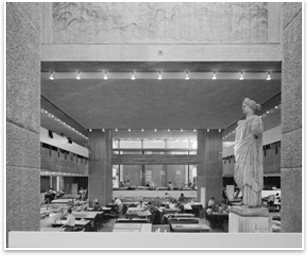

2. Architecture studios, Yale University Art & Architecture building, 1963.

Photograph © Ezra Stoller/Esto.

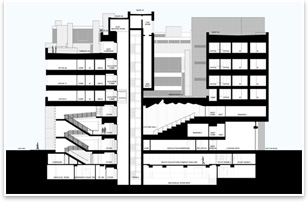

3. Section of Yale arts complex looking north. Courtesy Gwathmey Siegel & Associates Architects.

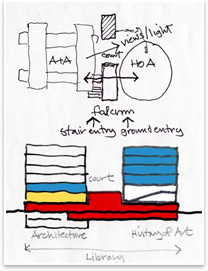

4. Original parti diagrams of Yale arts complex. Courtesy Gwathmey Siegel & Associates Architects.

5. Original parti diagram of Yale arts complex. Courtesy Gwathmey Siegel & Associates Architects.

6.Model of Yale arts complex showing York Street elevation by Gwathmey Siegel & Associates Architects. Photograph: Photo © Jock Pottle.

Visit the architect’s Web site.

Visit the AIA Committee on Design online.