| Discovering African Identity in African-American Architecture: Part II

Summary: Can you spot African identity in architecture when the architect is African American? The topic has been a hot one for years, with some arguing that any architect of any ancestry cannot help but bring in aspects of his or her culture, while those opposed claim that site, program, and budget are overpowering influences that limit the options to express any sort of racial or ethnic personality. A large cadre of architects and interested observers quite frankly admit they wouldn’t know what to look for. Here’s the second of two installments on African identity. Last month’s episode ran interviews with familiar figures such as Max Bond, FAIA, of Davis Brody Bond Aedas and David Lee, FAIA, of Stull & Lee. Today’s column gives a voice to William Stanley, FAIA, and Ivenue Love-Stanley, FAIA, of the established Atlanta-based firm Stanley, Love-Stanley, and Zevilla Jackson Preston, of small but vigorous Harlem-based J-P Design, Inc., and relates the phenomenon of the late Sam Mockbee of Rural Studio. You’ll also hear from author and interior designer Sharne Algotsson, who wrote African Style, making a case for producing African identity by observing five techniques and avoiding two others. William Stanley III, FAIA, and Ivenue Love-Stanley, FAIA,

SAK Astriking interiorfeature at Ebenezer were to be the eight “teaching windows,” whichwere a popular African device. Like stained glass windows in medieval churches, designed to show significant events and personalities to a population that could not read, teaching windows enhanced through pictures Africa’s “griot” or oral tradition of telling stories. The Ebenezer teaching windows were to chronicle the movement of Africans across the continent and on through the Diaspora into slavery, passing through the civil rights movement unto today.

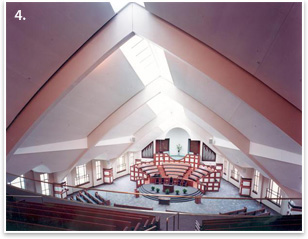

The entire Ebenezer structure is a heady brew of African motifs andCoptic Christian forms [an Ethiopian Christian religion which is the world’s oldest]. Its whole shape and profile are afrocentric. The roof is scalloped the way it is because that is the type of roofing form you find in parts of Africa. The standing seam develops a patina, from copper to brown to bluish green. It looks like the way they do thatching in Africa—a unidirectional laying of reed material. The scheme here was one large community house that has a thatched roof over it, and these forms cascade up and back down. And in some instances there’s an opening at the top of this thatching to let the light in.

STANLEY I try to express afrocentricity whenever possible and in as many ways as I can. Somebody has to advance afrocentricity beyond music and painting and jazz and discourse. These are symbols, and they can be manifested just as easily in architecture, the way they are in Africa. But to try to see how it fits into an architectural scheme without being limiting, and without being pure decoration, takes some doing. I see great beauty in African motifs, but I don’t walk around in African clothing—I don’t even own any. But the African spirit is so ingrained as part of my experience that it comes out even at worship and at play. SAK There are architects, mostly dyed-in-the-wool Modernists, who object to superimposed ornament. They view it as appliqué fashion.

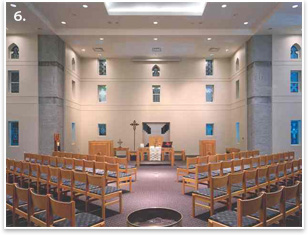

But in the end it is form as much as decoration that spells African identity—curvilinear forms that contrast with stark straight lines, as at Ebenezer. You can trace the fluidity of these forms to indigenous architecture of African towns and villages. We used window motifs, textures, and radical siting concepts from the famous Lalibela church in Ethiopia on the Lyke House Catholic Student Center at Atlanta University Center. The Center is sited so that from its southwest corner, the roof looks to be at the same level as the street—giving it a similar relationship to its site as the famous church at Lalibela in Ethiopia, which is carved down into a rock plateau.

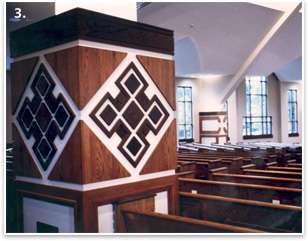

SAK The African motif doesn’t have to take up an entire building. It may only manifest itself as a totem or a glyph, or in a conference room, or in the way the architect handles an entrance wall, or a high profile ornament. STANLEY Many black people in America are descendants of Adinkras. The Ghanaians are great textile designers as a people, and each one of their woven patterns has a different meaning. We took these weavings [to Dobbs Plaza a nearby public square which is an homage to one of Atlanta’s civil rights pioneers] and occasionally used them to form patterns in brick in our buildings. Not only that, we also used them at openings in a granite wall [reminiscent of the one at Great Zimbabwe] and made of self-rusting CorTen steel. SAK As the balcony railing on her block-long apartment building on Upper Fifth Avenue in Harlem, Roberta Washington, FAIA, uses motifs drawn directly from Adinkras patterns.

Stanley’s own main body of work is largely devoid of African forms and detail. STANLEY Cutting to the chase, you’ve got to have a client who is willing first of all to express his afrocentricity as a client. He’s got to be willing to—I won’t say take the chance—but move in that direction, to commit to create a culturally rich and significant building. Not everybody is willing to go that far. Zevilla Jackson Preston

SAK As principal of a small Harlem-based practice (see career profile, AIArchitect, February 2007), for an architectural firm to be truly based on one’s culture, do you believe you had at some point to live that culture? Zevilla Jackson Preston (ZJP) It didn’t mean a white person or an Asian person couldn’t design [such a project], but to have this thing happen they would have had to experience it, at least from the way I approach architecture. My feeling is that African architecture is one that I define for myself. I believe that it happens in plan, not necessarily in form or in elevation or through any sort of appliqué. I believe that African people live differently from Western cultures. It’s a more communal type of space. It’s the indoor/outdoor room. African people’s sensibility and use of space is different, and the use of light is dictated by environmental conditions and texture and color, and that’s why I feel that one has to live the culture in order to manifest it.

ZJP Although I have a great deal of respect for Hughes’ efforts and work, I argue against his approach to teaching his version of afrocentrism to students in his studio who have never experienced African culture firsthand. They end up designing forms that he labels “afrocentric.” But that’s just an abstraction of a form. They take an object and stretch it and tweak it and make it a building, and that to me doesn’t make it African architecture … African architecture can’t be that superficial. Afrocentrism in architecture is a highly desirable ideal that faces complex challenges. But maybe there is a way. I would like some day to … do some experimental housing. You live in a city like New York where you have African immigrants, people from the Caribbean, who are more closely derived from the architecture of the [African] continent. Yet they live in apartment buildings in New York City basically designed on Western notions of living. So you’ll have one family—and not because they’re poor, it’s just because they live like this—run up and down stairs carrying a pot of food, from one “house” to the next, from one household to another. It’s about how people live; it’s not about economics. So they are forced to adapt, in a multiple dwelling building, to their communal way of living that they really want to have, but cannot, because of the way their apartment house is configured. SAK Today, more than 10 percent of the population of the United States is foreign-born. In another 20 years, there will no longer be a majority race or minority races or nationalities. Many are of African origin, typically from the Caribbean. This is an opportunity to design dwellings that make at least the effort, as you contend, to conform to the culture of the families who expect to be living there. ZJP Why then can’t we begin to design apartment buildings where they have a nuclear apartment unit, but then they have common kitchens and common dining rooms and common living rooms, and the extended family can rent it? Essentially, the apartment building then starts to look like a dormitory facility that you might get on a college campus. What’s wrong with that? But city housing agencies won’t listen. We can push the envelope. They’re spending so much money on housing right now just doing it the same way, because no one is suggesting any other way. No one is saying that every apartment building must be done on the nuclear apartment+common room model, but you can do two or three models. People move in, and you can see how it works.

The African American Academy, owned by Seattle Public Schools and designed by the late Mel Streeter, FAIA, offers an African-centered curriculum. Its most distinctive form is the circular dogon containing the library (see photo). The dogon has origins in Mali, Tanzania, and Uganda. The barrel roof which covers and identifies the entry (in background) is reminiscent of many of the roof forms found in Cameroon. The color palette employs rich red and copper hues with black, green, and yellow accents similar to indigenous clay brick and mud materials used in Africa. In its floor pattern the plan portrays a “river of life” that flows from entry to play area and simulates the River Niger, the connector of African nations.

For the rest, Madyun is skeptical about the idea of a black aesthetic in America, if by that term one means that black architects follow an identifiably different design aesthetic than other architects. “This is no more than asking the question: do Jewish architects or Asian architects practicing in America have a distinct aesthetic?” Sharne Algotsson and African Style Speaking at the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum in New York, Algotsson sought to illustrate how you make people feel they are in Africa. You do not, for example, put masks on walls because Africans don’t. Nor do you combine textures. You avoid current clichés. You try to capture the basics of African style. But how? Algotsson’s answer is comfortably inclusive: “…the more you know about Africa, the more easily you will be able to identify African style and incorporate it into your own home … The continent is home to more than 50 nations, and its terrain includes everything from deserts and rain forests to snowcapped mountains. Africa’s population spans an exotic range from nomadic tribes that follow their herds’ seasonal migration to young professionals who spend their days tracking the stock market … [African style] is not just about incorporating African masks and textiles into pretty interiors. Instead, it goes beyond stereotypes and revives the African tradition of hands-on, do-it-yourself, down-to-the-details design.” Algotsson’s five hallmarks of African style

African identity as defined in African Style is unlikely to meet the doctrinaire demands of either wing of the black architectural identity movement. The afrocentric wing will not be content with its appliqué approach, preferring more subtle design concepts using architectural and procedural rather than surface elements. The mainstream wing, committed as it is to a humanized Modernism, will balk at everything except the one feature Algotsson herself abhors—the nailing of masks to walls or other artificially imposed, non-authentic African motifs and objects. The Caribbean—and impact of the Old South A more promising candidate for an African feature is the porch—a shield against hot sun and heavy rain, and beyond that a social gathering place. People sit there; they visit. Site as source of African identity Boston architect David Lee, FAIA, doubts it, because opportunities to organize a whole new site are rare: “So much of what happens is within a grid or infill into stuff that’s already built. But it would be interesting to have a 300-acre site and begin to plan it on the lines of some traditional organizational principles, then see if in fact they would be valid in a North American context.” Conclusions On a more practical plane, to express ethnic or racial identity as structure, you need opportunity. But for black architects the prospects to do so are, and will likely remain, overshadowed by such reality factors as site, program, budget, schedule, climate, client preference, and user preference. If a black architect is to break through this screen of practicality and integrate, visibly or concealed within the process, such cultural factors into monuments to African identity, it will take a sweeping makeover of our current business culture, which elevates cash flow above style. Even if black architects were to struggle harder to capture African culture in their work—and there’s no reason why they should have to—there’s always the pressure on any minority grouping, namely, to be accepted in the general architectural community. So they end up designing in the same stylistic vocabulary as majority firms. “You look in the magazines,” argues Lee, “you see what gets published and what is held up as a standard for the profession, and you have to be influenced by it.” |

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

home

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Discovering African Identity in African-American Architecture, Part I

› Three Views on the Prospects of Increasing Diversity in the Profession

› Young African-American Women Architects Sharpen Ties to Their Communities

Next month’s column will take a look at the critical part played by the black architect’s client and patron, who has vision and opens up the prospect to do innovative work or simply demands safe but unimaginative solutions.

Did you know . . .

Film chronicles life of prolific California African American architect Paul Revere Williams. Williams is best known for his design of the theme building at Los Angeles International Airport; the Naval Base in Long Beach; and houses for dozens of movie stars including Frank Sinatra, Lon Chaney Sr., Lucille Ball, Barbara Stanwyck, and Tyrone Power. Much of his work was built on restricted sites he could not buy or consisting of properties he could not visit. The documentary Paul Revere Williams: a Legend in Architecture, is directed by Dave Kelly, Advanced Media Productions, Cal State Long Beach.

Black Enterprise Magazine recently unveiled results of its survey of companies’ efforts to promote a diverse workplace, according to an e-mail disseminated by architect Louis Smith. “No architecture firms were mentioned. In fact the industry as a whole was not mentioned,” Smith writes.

Adinkra symbols are derived from a proverb, a historical event, animal behavior, plant life, or shapes of animate and inanimate objects and are woven into cloths. They are traced to the Asante people of Ghana and Cote-d’Ivoire. Adinkra cloths, hand printed and hand embroidered, were made for and used exclusively by royalty and spiritual leaders in sacred ceremonies and rituals. American architects have adopted Adinkras as functional ornament, such as the railings in the apartment complex by Roberta Washington, FAIA, on Fifth Avenue, New York City. The examples at left are reproduced courtesy of Dr. Kwaku Ofori-Ansa. Copyright 2007 Dr Kwaku Ofori-Ansa.

Photos:

1. William Stanley III, FAIA

Ivenue Love-Stanley, FAIA

2. Scalloped roofline of Ebenezer Baptist Church

3. African motifs enliven the Ebenezer interior

4. View from the Ebenezer sanctuary balcony

5. Lyke House Catholic Student Center exterior

6. Lyke House Catholic Student Center interior

7. Zevilla Jackson Preston

8. The African American Academy dogon

Gail Kennard Madyun

Gail Kennard Madyun