| Discovering African Identity in African-American Architecture: Part I

How do you . . . recognize elements of architectural identity in work by a particular racial or ethnic group? Is it even possible? Summary: African-American architects constantly ask themselves whether there is such a thing as African identity in their architecture. In other words, would an observer, architecturally trained or not, spot/observe any African traits in the architect’s use of materials, siting, detailing, ornament, forms, and space flow that might identify a design as the work of an African-American architect?

Opposed are those who contend the argument lacks logic in the face of practical reality. For example:

This month’s episode in the AIArchitect’s diversity series offers answers to these divergent views, relying on some of America’s most resourceful African-American practitioners and scholars. Due to the breadth of the topic, you’ll see it in two parts. Look for part II next month. Every race and culture that emigrates from one place to another and mixes with the cultures already there ends up preserving a few of its characteristics and losing others to the prevailing cultural norm. The process inevitably brings with it pressures and tensions—poles of identity—ranging from cool adaptation to a strong, often rebellious mode that seeks to incorporate those roots in every creative act.

Mainstream firms of whatever racial composition see it the same way. A building and its form and finish are determined by site, climate, program, and the client’s stylistic preferences if any. Only then, they claim, can the architect—any architect—impose or integrate ideological or cultural content. After nearly 400 years in America, black Americans in general and black architects and builders in particular have built up characteristics that are as much American as they are African. Black architects, the assimilation party claims, don’t need afrocentricity to prove their origins. To do so may result in a self-conscious attempt to be what they are not. Majekodunmi looks across the Atlantic Ocean and sees a black professional who has far more in common with American culture than with Africa.

He would rather live with the unique psychosis of a person who does not know his history than invent an artificial past. He thinks aggressively that there is no African-American tradition in architecture, and that you cannot go about trying to resurrect an artificial past when “there’s too much to do in the present.” Fields suspects any effort to identify black elements in modern black-designed architecture because he mistrusts the visual apparatus used to make the judgment. In his 2000 book, Architecture in Black, published by Athlone Press, he sought to invent one using tools of cultural studies and Afro-American literary theory. As a founder and editor of the magazine Appendx (now APPX), an erudite scholarly journal, he has even objected to the term African American—because it is misleading: “Those who call themselves African American will assume that they have gained greater specificity by using this term, when in fact it is full of assumptions and contradictions . . . the term African homogenizes Africa: it neutralizes and makes indistinguishable cultural and political determinants that make Libyans different from Egyptians different from Nigerians different from South Africans.” There are exceptions. Churches serving African-American denominations, or community developments with heavily diversified populations, or buildings erected in climates that parallel those of Africa, justify such racial intervention. But in America, such climatic regions are rare, and they run straight into what he sees as the cardinal flaw of afrocentric philosophy—the assumption that there is such an entity as Africa. The most cursory look at a map reveals a huge range of climatic, topographic, and demographic venues. Which one is most afrocentric? Nigeria and its Yoruba artifacts? Cameroon and its religious masks? The desert monuments of the Sahara and North Africa? The sphinxes of Egypt? The great prairies of East Africa? The heavily built up townships of South Africa? APPX sees the relationship between architecture and blackness as a matter of fact, albeit a very complex one. Hughes’s afrocentrism Brooklyn-born Hughes’ academic credentials include a bachelor’s degree from Columbia, a graduate fellowship at Princeton, a master’s in urban planning from the City University of New York, and a Fulbright fellowship. He has been on the Kent State University architecture school faculty since 1985. He argues in his book Afrocentric Architecture: A Design Primer [Greyden Press, 1994]. that African contributions to world culture have been stifled under what he calls “the social implications and political ramifications of a eurocentric hegemony that limited honest intellectual review.” Yet, he claims, architectural concepts such as form, monumentality, order, structure, detail, and hierarchy all have their origins in Africa. He cites the pyramids of Ancient Egypt and the abstract anthromorphism of West African ceremonial masks as having influenced the looks of buildings and the planning of spaces throughout the world. The traits go beyond architecture. For Hughes, they include: life and customs, music, spirituality, genealogy, environment, and natural landscape, all of which the African-American architects must integrate into their designs. He cites the organic tradition of Africa, where the form of an object is derived directly from its function and from its physical setting. Art for art’s sake has no place. Quite the opposite: the links between a designed object, whether it is a knife, a mask, a building, or a ceremonial space linking buildings, arise strictly to accommodate the function of that object or place. Grant, slavery and afrocentrism

Grant ascribes the era of strongest black identity to the long period of slavery. Only under slavery did black artisans, designers, and builders have undisputed control of building, at least in the Southern states. “In a perverse way,” he writes in “Accommodation and Resistance,” “the most active period of African-American involvement in design and building was during the period of slavery. African craftsmen-slaves were the primary builders of the South, usually under the strict control of a ‘master,’ yet often in the role of ‘supervisor-designer-builder.’ As a consequence, according to Booker T. Washington, writing in Up from Slavery, white people lost the skill of building, and after emancipation had to rely for the design, construction and, furniture making on former slave-artisans. Sadly, little of Africa and African identity visibly found its way into building, notes Grant: “Unlike the uniquely African-American influence in gospel music and other personal arts developed within the slave experience, architecture was much too visible, public and permanent to allow clear African motifs and references to be expressed.” But not entirely so. He found subtle influences in the South, in and around the plantations and in the towns and cities. Examples showed up in ironwork and woodcarving and, according to Richard K. Dozier’s “The Black Architectural Experience,” a section in African American Architects in Current Practice, Jack Travis, ed. (Princeton Architectural Press, 1991), in features such as steep hip roofs, wide overhanging roofs, central fireplaces, porches, and earth and moss construction. Grant cites Carl Anthony (“The Big House and the Slave Quarters,” Part I, Landscape 20/3, spring 1976, and Part II, Landscape 21/1, fall 1976) as spotting in the tidewater plantations of Virginia modest outbuildings that “seemed genuinely African in proportion, siting, or construction.” Some of these, he felt, created “the visual effect of a piece of an African village with its multiplicity of dwelling units and granaries.”

But as he looks at the work of majority architects, Lee points out that by contrast whenever Western European themes are integrated into their work, no one seems to view that as

“African art varies from tribe to tribe, from village to village. There are certain themes that run through, but there are great differences, so afrocentrism, to the extent that it implies a unitary culture, is an oversimplification. Next, it ignores the material aspects of culture, which is part of a whole bunch of things—climate, history, available materials.”

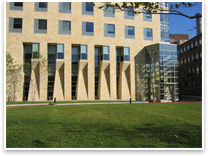

False premises I “So I’m not opposed to the fact that people recognize their heritage, but I’m bothered by oversimplification of the influences that have shaped modern culture.” Bond rejects Majekodunmi’s precept to African Americans that “you're Americans. Why deny it?”: “We are Americans but there is a strong African-American cultural tradition. That tradition, I believe, is represented in my work.” (See the Birmingham Institute.) To Bond, that is what counts. So it’s hard to find any particular set of attributes unique to black architecture in America. It’s not so much for lack of materials, colors, and textures, but simply because black designers want to be accepted in the general architectural community. So they end up designing in the same stylistic vocabulary as majority firms. “You look in the magazines,” says Lee, “you see what gets published, what is held up as a standard for the profession, and you have to be influenced by it.”

|

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

home

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Doer’s Profile: Curtis Moody, FAIA

› Corporate and Public Architects: Seeing from the Client’s Side

› Architects Engaged with Civic Leadership

Look for “Discovering African Identity in African-American Architecture: Part II” next month.

Did you know . . .

500 new hotels. In a move that places African Americans in the patronage driver’s seat, the National Association of Black Hotel Owners, Operators, and Developers plans to build 500 new African American owned hotels by the end of 2010. NABHOOD hopes to open 122 of them this year, bringing the national total to 289. There are reportedly some 50,000 hotels in the U.S., so the present ratio of black-owned hotels isn't large, but the initiative is a strong upbeat sign. Let us see how many of the design commissions will go to black architects. Seldom has there been a greater opportunity.

African-British architect David Adjaye keeps drawing more limelight as a major exhibit of his work opens July 18 at the Studio Museum of Harlem. The show tracks 10 of his projects from start to finish. Adjaye has lectured in New York City, and the Harvard Graduate Scholl of Design this year had a show of his work that took up the entire spacious entrance hall.

Harlem’s first tall office building since 1973 is to rise at 125th Street and Park Avenue. Vornado Realty Trust has chosen Swanke Hayden Connell Architects, a large Manhattan-based majority-owned firm, as the architect. “We hope they are successful in getting tenants,” Harlem Community Development Corporation president Curtis Archer told Architectural Record. No word whether an African American architect was considered.

AIA Seattle’s diversity scholarship has been named after outgoing longtime Executive Director Marga Rose Hancock, Hon AIA.

Boston Architectural College has named a full-time director of Human Resources and Diversity. Michael James was previously chief of Equal Opportunity and Diversity at Massachusetts Bay Community Railroad.

Images

Image 1: “Builders #2,” by Jacob Lawrence, 1968. Photo: The Jacob and Gwendolyn Lawrence Foundation/Art Resource, N.Y.

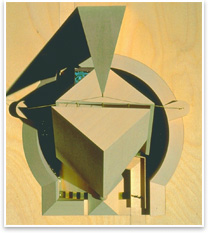

Image 2: Variations of pyramidal forms within a framing circle derives from forms found in many African countries. Rendering courtesy of Stull and Lee.

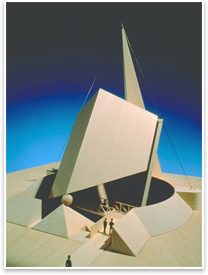

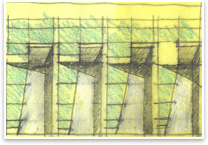

Image 3: The pyramid/circle forms in the Middle Passage monument design for Boston Harbor, by Stull and Lee are intuitive references to African architecture. Rendering courtesy of Stull and Lee.

Image 4: Darell Fields. Photo by Russell Cothran.

Image 5: M. David Lee, FAIA. Photo courtesy of the architect.

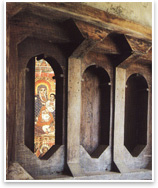

Image 6: Details of Triforate windows at the Church of Narga Sellase in Ethiopia. Photo courtesy M. David Lee, FAIA.

Images 7&8: Lee’s sketches based on the Triforate window motifs for Northeastern University’s John D. O’Bryant African American Institute. Renderings courtesy M. David Lee, FAIA.

Image 9: O’Bryant African-American Institute main façade, by Stull and Lee Architects, based on the Narga Sellase form. Photo by M. David Lee, FAIA.

Image 10: Max Bond, FAIA. Photo by Fred Conrad, the New York Times.

Image 11: The Dillard University International Center for Economic Freedom, New Orleans, portico reflects the white brick classical buildings against dark green foliage typical at Dillard. Architect: Davis Brody Bond. Photo by Neil Alexander, Photographer.

Image 12: Dillard Center for Economic Freedom syncopated glass wall by Davis Brody Bond. Photo by Neil Alexander, Photographer.

Image 13: Louis Armstrong print in the Dillard Center lobby by Davis Brody Bond. Photo by Neil Alexander, Photographer.

Fields’ America

Fields’ America David Lee and the clout of Modernism

David Lee and the clout of Modernism

Max Bond: “Afrocentrism isn’t just a style”

Max Bond: “Afrocentrism isn’t just a style”