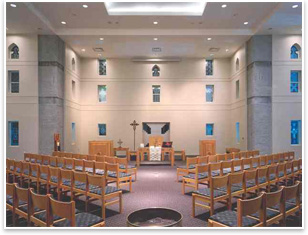

| Diversity Three Views on the Prospects of Increasing Diversity in the Profession How do you . . . entice talented persons of color to become architects. Summary: This month’s diversity column features two successful black-owned firms situated on opposite ends of the country. In Atlanta, William J. Stanley, III, FAIA, and Ivenue Love-Stanley, FAIA, are the principals in Stanley-Love Stanley, PC. In Seattle, Donald I. King, FAIA, founded DKA. Both firms have acknowledged prevailing neo-Modernist influences in their work, though they have largely eschewed the high-tech vocabulary of blobs, folds, and boxes common in the work of some younger-generation firms. Each has focused on using and transforming non-European historic influences—King from the tropics and the world of the Mayas, Stanley and Love-Stanley from Africa. Both firms boast tight links to their social and religious communities. Profile: William J. Stanley III, FAIA and Ivenue Love-Stanley, FAIA These “firsts” identify the founders of a firm that has become one of the nation’s largest African-American practices, and includes such work as the landmark Ebenezer Baptist Church New Horizon Sanctuary (where Dr Martin Luther King Jr.’s father was pastor), Lyke House, Turner Chapel AME Church, and the Fort Valley (Ga.) State University Health and Physical Education Building (see photos).

Kliment: What is needed to enlarge the numbers and ratio of black students, faculty, and architects? Stanley, Love-Stanley: A very intensive and multi-faceted “frontal attack” is essential on what is perhaps the most glaring and shameful disparity in any traditional American profession. By and large, women have made strides and are nearing equality in enrollment at schools of architecture. Yet they have not gained any significantly higher representation in the marketplace as registered architects, partners, or principals of firms. Consequently, the female gender questions and the African-American questions must be looked upon as separate in complexity, degree of disparity, and range of critical options. As for the student and faculty ratios—it is the classical chicken-and-egg scenario. Fewer opportunities to be introduced to the profession mean fewer students will become interested in pursuing architecture as a career. Fewer applicants lessen support, and little or no scholarship opportunities often lead to little or no recruitment efforts by colleges and universities. The absence of aggressive recruitment and a dearth of welcoming environments lead to fewer undergraduates. Fewer undergraduates mean that fewer students will move on to graduate schools. Fewer graduate students will yield fewer potential faculty members. Fewer options for graduates mean fewer persons can enter IDP programs and gain internships with firms. Fewer interns mean fewer persons will become registered architects. Fewer RAs mean fewer role models. Fewer role models mean fewer people will battle to crash through the glass ceiling of partnerships or positions as principals—these opportunities are virtually non-existent in firms of any size—large, midsize, or small. The problems are immense ... and we have been talking about them for generations. Until the profession at large, the AIA and all of its member firms, all of the country’s schools of architecture—including historic black colleges and universities (HBCUs) take their heads out of the sand, we will never begin to address this national disgrace. The engineers, lawyers, and doctors wised up years ago. They found unilateral approaches to these problems, while architecture has languished in a morass of excuses, work-arounds, and marginally successful ‘feel good’ programs; the big picture remains out of focus. Ivenue’s and my challenges were immeasurable. We both crashed into the glass ceilings at the large firms where we worked. Even today, there are virtually no principals, partners, or senior architects with whom we can identify as role models. The obvious option for us and for others was to start our own firm. Our role model was Nelson Harris, AIA, NOMA—my cousin who practiced in Chicago, Cleveland, and Youngstown, Ohio. As a child in Atlanta during the 1950s, there were no black architects and no accommodations for persons of color to stay in hotels or frequent other places of business. As a result, Nelson chose to stay with our family when he came to Atlanta for business meetings or to exhibit at the various religious conventions, which represented the area of practice for much of his client base. As a child, I was captivated by his renderings and blueprints.

Hard work and sacrifice were our constant companions. Neither of us had ever owned a new car until we had been married for 15 years. Only then did we agree to pay $16,000 cash for a very basic Jeep. Both of our subsequent vehicle purchases have been used cars. Now we are debt free and own our own building (mortgage free) in midtown Atlanta—one of Atlanta hottest real estate markets. We still pull all-nighters. Whenever our staff has project deadlines, we typically work as long as they do. Kliment: How responsible are well-to-do black private and corporate patrons in retaining architects of color? Stanley, Love-Stanley: Those well-heeled people of color, who should be counted on as the quintessential client base for black practitioners, often struggle with their own ethnicities and the need to prove that they have arrived by selecting a star or (“near star”) architect for their commissions. These commissions are usually homes or business interiors. Many very talented designers of color never have the exposure to those clients with real money. So many of the more successful entertainers and sports figures have the 5th Ave./Rodeo Drive mentality that the “white man’s ice is always colder”—an old saying in the black community. This simply means that they do not trust the quality they may receive from any practitioner who looks like them. They usually relegate those important decisions to their handlers or financial advisors. Insofar as personal services are concerned, the only thing even remotely black in their lives are their church and their hairstylist. Even then it is not a given that their personal physicians and lawyers will be black. Their realtors, car salesmen, and wardrobe consultants are often white. Of course, there are exceptions. But those only exist in places where there are strong and mature black business communities, such as Atlanta and Chicago.

The money is there. There are enough dollars in this country for everyone in the black architectural community to prosper. The annual spending of African Americans in this country is equal to that of the gross national product of the world’s 16th richest nation. If just half of those revenues were deployed wisely and allowed to circulate through the community’s economy just two times, there would be enough wealth generated to insure the financial success and prosperity of all existing black businesses. Kliment: Why are the legal and medical professions so much more diversified than architecture? Stanley, Love-Stanley: The answer is simple ... most people go to a physician many times in their lives. Black physicians, HBCU schools of medicine, the powerful National Medical Association, the Association of Black Cardiologists, et al. have developed a century-old tradition of black medical professionals serving black patients. (Dentists, especially cosmetic practitioners, receive a little less patronage.) Over the years, the white medical profession has had to follow suit and raise the level of awareness about black health disparities in the black community to the point of a national conversation. Although black/white medical partnerships are less common, there are a few well-established mixed practices. There is less of a propensity for “salt and pepper” (black and white) design firms to develop naturally and be sustained for any significant length of time. It is more likely that joint ventures (often of the shotgun marriage variety) will continue to be the manner in which black and white business interests will be served mutually. Black politicians and their supporters recognized long ago that for municipal bond deals to be consummated, there needed to be significant involvement by black law firms, as well as at least one black law partner in every majority law firm. During the Civil Rights movement, majority schools of law aggressively recruited the brightest black pre-law undergraduates to their campuses. The profession as a whole created internships, clerk positions, and eventually fast tracks to partnerships for a very elite group of minority barristers. The leading HBCU schools of law raised the bar but were often left out in the quest for attracting the most talented law students. Most people require the services of a lawyer at some time during their lives. The same is not true for architects. Only a very few persons (or businesses, for that matter) will ever need our services; therefore, the business model has to be a different one. More young people will identify with a black doctor or lawyer than will ever have the same attraction to an architect or other design professional. Young people simply think (and no doubt rightly so) that they can make a lot more money in either of those professions. The absence of role models in legitimate architecture firms means that they do not believe the financial rewards apply in our profession. Profile: Donald I. King, FAIA For example, his Sea-Mar Community Care Center is one of 16 health-care facilities he has designed in western Washington State for this Hispanic/Latino community health-care provider. The Sea-Mar buildings remind one of the most sophisticated indigenous architecture of Mayan Mexico and Central America. One side of the building is covered with a large-scale diamond pattern, as is the floor in the lobby. The entrance, one of the corners of the square building, is rounded, and there are columns with cornices on the facade and an angled roof. These are all design elements found in the Mayan ruins of Mita, Palenque, and the Governor’s Palace and Nunnery at Uxmal. It’s hard to know which of the design elements in King’s building is derived from his research into ethnic building styles and which spring from his own racial memory. King admits that he deliberately designs “outside the European model.” He looks instead to Africa, tropical, and other examples of Pre-Columbian architecture “because their climate-responsive site planning, decorative facades, and day-lit and ventilated spaces represent natural responses.” As the contours and detailing of King’s buildings show, however, his designs do far more than adapt to the climate and landscape of tropical architecture. In his search for a definition of non-European-derived architecture, King has created a design vocabulary in which modern building methods and non-Western design motifs co-exist amicably to form some of the few examples of a genuine pre-colonial style of architecture.

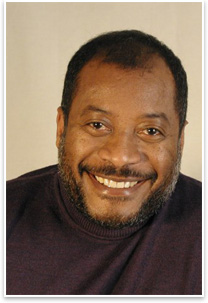

King is a rebel and seems to relish the role. He admits that what motivates him to do his best and to work so hard—King says that he has no life outside of his work—is the public perception that black men and women can’t make it because architecture is “an upper income white man’s profession.” African Americans, he says, are not given the opportunity to stumble and recover. He notes a tremendous difference between the way he and his staff are treated by community-based clients and his treatment by corporate clients. The community-based client, who has difficulty paying for services, has an attitude of respect. By contrast, corporate clients take him and his staff for granted. Racism may be only partly responsible for their cavalier manner, he concedes: “That’s just the way some people treat others.” While King argues there are now more career opportunities for architects of color, there still aren’t enough and one reason is that so few African Americans design new buildings. “We buy, convert, and reuse. For example, Seattle’s Langston Hughes Cultural Arts Center is located in a former Jewish bakery. Similarly, many black churches were converted from other church denominations.” He remains concerned about the problems of black architects overcoming what he refers to as negative expectations on the part of clients. In light of the hurdles he and other black architects have had to overcome, what gives him the most satisfaction is the fact that he is a good designer with a successful practice—despite the fact that he hasn’t always played up the trendy architectural design features that win awards. Born in Port Huron, Mich., in 1949, he was the youngest of six children. A single mother from the time Donald was five years old, his mother was able to inspire her six children to earn university degrees and four to gain master’s degrees. In practice for nearly 30 years, he has led DKA in the planning and design of more than 350 projects, virtually all of them community-based. Here’s what King told Kliment about the prospects of black architects in America. Kliment: Why are the legal and medical professions far more diversified than architecture? King: Architecture is a luxury profession, so much so that members of the profession have been historically considered by their wealthy patrons as class equals. Although this is an antiquated view, some people still cling to the idea that only those members of society with a lineage of financial privilege are competent to practice. Until recently, the American privileged class was made up mainly of Euro-Americans who were wealthy enough to pay for the construction of significant buildings requiring licensed professionals. For many years this belief that only members of the upper class were suitable for the profession was not seen as racist due to the rationalization that many non-whites were excluded from the profession not because of race, but because of class status, whereas the necessity of medical and legal services across all class levels and races provided more opportunities for African Americans to become doctors and lawyers. Kliment: What is holding back the ratio of African-American practitioners in the profession? King: After 30 years in the profession, I have seen some improvement. However, there is still limited exposure of architecture as an attainable career in the African-American community. Very few black college-bound students can identify role models among the current small numbers of black architects. For most it’s not a career choice, nor is it in their parents’ minds as a possible career direction. So promising black students who compare architecture to other more financially lucrative career choices are less than inspired by the low visibility of successful black architects. Many black students, after they survive the rigors and isolation in mainstream architecture schools (the six accredited HBCUs aside), leave the profession after a few years due to lack of attractive job opportunities. Kliment: Who needs to act to bring the ratio (today about 1.5 percent of the 102,000 registered architects are black) in line with their numbers in the population? (about 12.5 percent)? King: We need a sustained effort by members of the profession, supported by the schools of architecture, NOMA, and the AIA. Black architects need to step up and become more visible in their communities and act to encourage and consult with the youth as they make their choices of careers. Kliment: What should wealthy and/or celebrity black clients and patrons be doing in advancing the work of black architects? King: I see some advances here. Notable patrons include Bill and Camille Cosby, who purposefully sought an African-American architect for their sponsored facility at Spelman College, Atlanta. |

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› The Educators

› Young African American Women Sharpen Ties to Their Communities

› Making Partner in the Majority-Owned Practice

Ebenezer Baptist Church New Horizon Sanctuary (1999) was inspired by an array of African motifs and forms, beginning with its profile. Photo by Harrison Northcut.

Sea-Mar Community Care Center is one of 16 health-care facilities designed for a Hispanic/Latino community provider in Western Washington. The design makes liberal use of Mayan motifs. Photos copyright Steve Keating.

Did you know . . . ?

Museum for African Art for New York City. On April 5, New York State Senator Bill Perkins and City Councilwoman Melissa Mark-Viverito met with a thin turnout of local architects and a local zoning/building code consultant who aired their concerns. The decision was made to write letters to include the director of the museum and Mayor Bloomberg expressing disappointment in the missed opportunity to select a minority architect. There was also talk of a press conference on the site. Replacing Robert Stern as the architect was not considered or discussed. The only printed media publication on the matter so far has been a letter to the editor of Architect magazine from Stephen Kliment, published in the April issue.

Diversity: Planning Real Action. Some 16 laborers in the diversity vineyard met April 20 at the Harvard Faculty Club in Cambridge under the aegis of the Loeb Fellowship at the Harvard Design School. R. Steven Lewis, AIA, NOMA, a 2006-2007 Loeb Fellow, organized and managed the group meeting , which included AIA President-elect Marshal Purnell, FAIA; GSA Chief Architect Leslie Shepherd, AIA; and BAC President Ted Landsmark, Assoc. AIA. The session concluded with a series of practical recommendations, which Steve Lewis and staff are converting into a hard-nosed action plan to be published later this year.

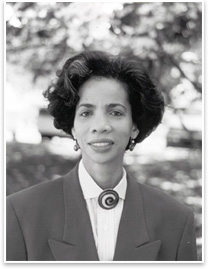

William Stanley founded his practice in 1977 with his wife Ivenue Love-Stanley. Stanley graduated from the Georgia Institute of Technology in 1972, and Ivenue in 1977. Each has a record for breaking barriers. Bill was Georgia Tech’s first black architecture graduate; Ivenue was its first black woman graduate. In 1975, Bill became the youngest African American to be registered in the South. Ivenue was the first black woman to receive a license in a Southeastern state. In 2001, she became only the fourth African-American woman in the 144 years of the AIA to be elevated to fellowship.

William Stanley founded his practice in 1977 with his wife Ivenue Love-Stanley. Stanley graduated from the Georgia Institute of Technology in 1972, and Ivenue in 1977. Each has a record for breaking barriers. Bill was Georgia Tech’s first black architecture graduate; Ivenue was its first black woman graduate. In 1975, Bill became the youngest African American to be registered in the South. Ivenue was the first black woman to receive a license in a Southeastern state. In 2001, she became only the fourth African-American woman in the 144 years of the AIA to be elevated to fellowship. Here, the two partners offer blunt answers to Kliment’s questions:

Here, the two partners offer blunt answers to Kliment’s questions:

A major player in the Pacific Northwest, Donald King designs elegantly but has never lost the common touch. For King, the community reigns, and his design track record reveals an array of humanly scaled structures, with many features traceable to non-European influences.

A major player in the Pacific Northwest, Donald King designs elegantly but has never lost the common touch. For King, the community reigns, and his design track record reveals an array of humanly scaled structures, with many features traceable to non-European influences.