Having It Both Ways by Zach Mortice How do you . . . plan the expansion of a major educational institution with respect for the surrounding neighborhood? Summary: Columbia University is planning a 17-acre new campus north of its main Morningside Heights university grounds. The new campus will juxtapose sleek, Modern forms next to West Harlem’s gritty, industrial streetscapes in an attempt to create a campus that invites the neighborhood into the school with glass facades, green spaces, public parks, and wide building setbacks. To ensure a smooth transition of development, Columbia will have to work with community members and local businesses that might be displaced by the expansion.

“I think this will mean a change in the architectural character to a certain extent, but hopefully not in the range and the diversity [of neighborhood businesses],” says Marilyn Jordan Taylor, FAIA, partner of urban design and planning at Skidmore Owings and Merrill. SOM is handling the urban planning and approval process for the project.

“The tenants will have to live up to those performance qualities,” says Jordan Taylor. A tale of two campuses

“This isn’t a campus defined by gates and walls,” says Columbia’s Director of Construction Coordination and Facilities Warren Whitlock on the development’s Web site. The plan will also preserve several old warehouses and factories, like the Studebaker building on 131st St., which will become university administrative offices. “We’re treating them as if they are landmarks and giving them the kind of respect that they deserve, and then adding to it, quite explicitly, buildings that contrast,” says Jordan Taylor. Though not designed yet, the new Columbia buildings’ sleek and modern metal and glass forms promise to stand out next to their industrial masonry surroundings, a contrast Jordan Taylor calls “complementing history rather than trying to recreate it.”

Beyond this, Columbia has building footprints and forms for 17 structures. Renzo Piano’s Building Workshop is the design architect for the project, and Jordan Taylor’s SOM has been working with the Italian firm for several years and handed design responsibilities to them this winter. Local New York-based firm Davis Brody Bond Aedas signed on this summer as the architect of record.

In a press release, Columbia Senior Executive Vice President Robert Kasdin pledged that the university is “absolutely committed to ensuring that these community members will have equal or better affordable housing in the area, and we are working to achieve this result.” The development plan’s Web site says the school might help with housing searches and moving costs, but the university hasn’t commented further on how they might help local residents and businesses that need to relocate.

The question, says Jordan Taylor, is: “How do we tie [these different elements] together enough but at the same time not make it feel too homogenized?” |

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

home

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Master Plan for Wuxi, China, Aims to Create an Urban Nucleus

› HOK Master Plans $300 Million Mixed Use in Atlanta

› Architects Engaged with Civic Leadership

Photos:

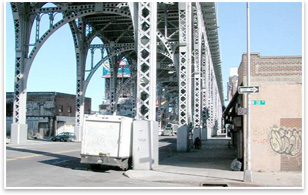

1. Current view looking north on 12th Ave.

2. Proposed view north on 12th Ave.

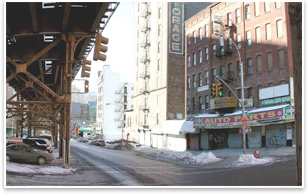

3. Current view looking south on Broadway at 131st St.

4. Proposed view south on Broadway at 131st St.

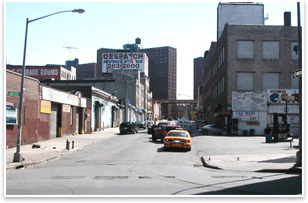

5. Current view looking east on 130th St.

6. Proposed view east on 130th St.

In all cases, the “after” renderings are intended only as rough representations of the streetscape as it might look and are not actual design proposals.

For their part, Jordan Taylor and SOM aren’t interested in whitewashing West Harlem and Manhattanville of its diverse, urban texture. “A certain amount of messiness goes with that,” she says.

For their part, Jordan Taylor and SOM aren’t interested in whitewashing West Harlem and Manhattanville of its diverse, urban texture. “A certain amount of messiness goes with that,” she says.