| DIVERSITY Architects Engaged with Civic Leadership Summary: Whatever their racial or gender background, the number of architects who were ever engaged in public service is low. The number of architects of color and of women is even lower. Among all architects, perhaps best known, at least since Thomas Jefferson, is Richard Swett, FAIA, who served in the Congress 1990-’94 and later as U.S. ambassador to Denmark. Among architects of color, Harvey B. Gantt, FAIA, is famous for his stint as mayor of Charlotte 1983-’87 before rejoining his firm there, Gantt Huberman Architects. For this month’s AIArchitect diversity column, we have selected three practitioners of color—two architects and one architecture-graduate-turned-planner. William A. Gilchrist, FAIA, has been director of the Department of Planning, Engineering, and Permits for the City of Birmingham since 1993. Toni Griffin, AIA, is a former deputy director for neighborhood planning and revitalization planning (two departments she ran concurrently) in the Washington, D.C., Office of Planning. Toni takes over in June as Newark director of community development. Mitchell Silver PP AICP is director of the Department of City Planning and Urban Design Center in Raleigh. They bring to the table a wealth of experience, vigor, and resilience.

He has chaired the committee that oversees the AIA Regional/Urban Design Assistance Teams (R/UDATs). He’s a trustee of the Urban Land Institute, a nationwide voice in the field of land-use practices, and is vice chairman of its executive committee.

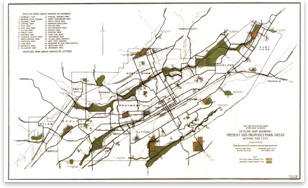

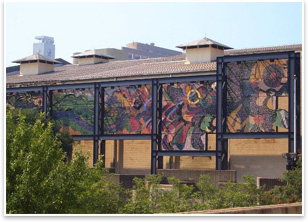

Finally, he excels as a communicator, a priceless skill in an era when design professionals often trip over the English tongue through muddy language and incomprehensible jargon. He has been interviewed on National Public Radio, appeared on PBS’s The News Hour with Jim Lehrer, and speaks often on urbanism, regional planning, citizen participation in the public realm, and the history of urban settlement. He writes on occasion for the Birmingham News, a Pulitzer-Prize-winning newspaper. SAK: What have been your most fulfilling projects since you became director of the department? Back then, of course, Birmingham had very strict segregation—probably the strictest in the nation. And the idea of having a linear system that would connect the parks’ multiple neighborhoods was not something they were willing to do. From a social and political angle, it was just not a project that was going to gain support. The Olmsted brothers did the master plan update, with the linear park as its crown jewel. That’s how matters remained for three generations. Then, after repeated floods, mainly in residential areas, my department and I went to work with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers on what was the largest acquisition project in the Corps’ history before Katrina. It entailed buying distressed properties, primarily residential, along the flood plain. What made this important, from a planning, urban design, and equity aspect, was that it undid the zoning overlay of 1926. The only uses then allowed along Village Creek were either industrial or what was then called Negro housing. So the dominant impact of repeated flood incidents along that creek disproportionately impacted African Americans and people who had no legal recourse about quitting those areas. And remember it wasn’t just the market that was working there, it was the law that was keeping those families in harm’s way. So my having the opportunity to come, 80 years later, and effect the change that both gets the citizens out of harm’s way and leaves the communities and the city and the region as a whole with an amenity, with a linear park system—to me, I don’t know that it gets much better than that, in terms of the work we do. SAK: I hear the Boutwell Auditorium downtown has been another fulfilling project for you. A consortium made up of the Birmingham Museum of Art, an art studio called Space One Eleven, my department at City Hall, a private architect, and a contractor worked together to do something a lot more meaningful and substantial than simply restoring the side of an auditorium. Now the art museum, along with Space One Eleven, had done some work with children from a local public housing project. The kids came through the art museum, which has the largest collection of Wedgwood on public display in North America. They went through the Wedgwood Collection and saw the images inlaid in the blue or green Wedgwood, then went back to Space One Eleven to cast tiles on that theme. Rather than painting the wall, maybe we could build an armature, cast tiles, and make a composite image. These would be tiles the kids would create, and it would be a lasting contribution in honor of the Olympics coming to Birmingham in 1996. The composite of eight panels—where one child might have a tiger in the middle, or an image of his mom, or of a house—makes this a lasting impressionistic landscape image of Birmingham hosting the Olympics. There was television coverage. NEA publicized it to Congress as one of its model projects in urban areas. It turned out very well. It was very fulfilling. Another highly satisfying feat was the Civil Rights Institute. It predated my time at City Hall, but I worked as a program manager. It was my introduction to Birmingham. I had an opportunity to work again with Max Bond, FAIA, who was architect for the institute, with R. L. Brown & Associates doing final construction documents and the construction phase. The programming, both for the building and the exhibit, dictated an integrated approach. We worked on the task force with the American History Workshop, out of Brooklyn, and with a team of top local scholars. That was a wonderful experience. Finally there has been my service on the many advisory panels, R/UDAT, and the Urban Land Institute. Those have been very fulfilling. I get out to see what other communities are doing, what issues they’re facing, and what are the hurdles challenging their advance. It’s a great opportunity to work with gifted colleagues in the design, development, and economics of the profession. Most memorable, I guess, was New Orleans, where I chaired the subcommittee for city planning and design on the ULI’s 40-plus professional advisory team to the city after Katrina. Just looking at what that city was facing and coming up with some strategy that might get them initially focused on how to rebuild and reconstitute, and also have long-term application, in the short timeframe we had to produce it, and under the conditions in which it had to be developed, with most of your population away from the place, was daunting. SAK: What recommendations did you come up with? So there were real challenges, given that you didn’t have the infrastructure of government, non-governmental organizations, or even private sector to make it all work the way you do with most other plans. Since then, Edward Blakely has been appointed post-Katrina planning czar to help get things on track. Now a lot of the population has returned to the region, and the downtown areas are active by night, always a good indicator for future prospects. SAK: Do you see yourself primarily as a planner or as an architect? To do that, you are responsible in my position for integrating those professions into a coherent development of a city—the landscape architect, the architect, the planner, the land-use and zoning expert, the economist—it’s your responsibility to bring that together so it works for the community that’s going to live in that place. So I see myself as a convener. Architecture is my profession, but, ultimately, I’m really a convener across all the disciplines that make a city. SAK: What made you decide to go into architecture? SAK: What was there in your family background that encouraged you? So Max was a large and early influence. Then anytime there was an article in any magazine about architecture, particularly African American, family members would get it to me. I remember Black Enterprise had a piece in the early 1970s about black architects. Max and his then-partner Donald Ryder were among the first interviewed and discussed in the article. The article covered black architects across the country, challenges they faced, projects they had done. Thus encouraged, I went to MIT to study architecture. SAK: As you know, the ratio of black architects in the profession is very low. What role should well-to-do African American patrons and clients, public as well as private sector, play in advancing African Americans as architects?

Griffin is no stranger to the stresses and strains of public service. For five years (2000-2005) she worked concurrently as deputy director for neighborhood planning and revitalization planning in the Washington, D.C. ,Office of Planning, then moved to the Anacostia (D.C.) Waterfront Corporation, where she was vice president of design. Prior to Washington, D.C., she was vice president for planning and tourism development in the Upper Manhattan Empowerment Zone Development Corporation.

Before any of this, she cut her teeth at the Chicago office of Skidmore Owings & Merrill, which she joined in 1986, the year she earned her BArch from the University of Notre Dame. She served there for 12 years, became an associate partner, and was asked to start up SOM’s office in Detroit managing the General Motors World Headquarters project. SAK: What do you consider your most satisfying accomplishments? The architecture work was slowing down, but the planning work was still strong and I ended up working in that department. That’s when I discovered a passion I really hadn't realized, urban design and urban planning. I ended up working on larger-scale strategic planning on the near west side of Chicago on the site of the 1968 riots and did a lot of neighborhood planning. I also got to work on the south side of Chicago where I grew up. I worked with a number of business leaders as well as community constituents. I enjoyed the breadth of issues. Right before leaving SOM, I opened our office in Detroit. We partnered with General Motors, which was relocating its world headquarters, and the developer Gerald Hines, who served as development consultant to GM. This was a defining project for me because it combined everything from my experience. We were managing redevelopment of the property. We were working with them to help assess the vacant land next to the site and really think about how their corporate contribution could help reinvigorate downtown Detroit. It was a combination of urban design and planning and architecture and the impact that trained professionals can have in shaping a city for its people. SAK: Then you took a year off [1997/98] for a Loeb fellowship at Harvard, which accepts promising design professionals in mid-career and allows them to take stock and redirect their careers. I was there for two years. My role was defined based on the work I had done in Chicago, particularly on the near South Side, which is analogous to the demographics of Harlem. It was the area where, during the 1910s and ’20s, blacks from the South migrated to Chicago. It was a self-contained, segregated but prosperous African-American community. My Loeb year was spent on studying how those types of communities could redevelop and retain of their cultural heritage and character. So going to work in Harlem, a Mecca of African American life in the United States, appealed to me, above all working for a quasi-public agency that also had the resources to carry out its policies. We were creating programs and funding sources that actually were designed to help communities plan and fund projects to promote tourism. It demanded planning that values ethnic diversity and ethnic cultures and builds from the work of grassroots efforts. SAK: Was that when you had the call from Washington? SAK: So what did you do? We collaborated with several highly respected design consultants. The city was growing fast, and we wanted to make sure that design was compatible within existing communities but also forward thinking, it being the nation’s capital with a legacy of progressive planning. We wanted to make sure that going into the 21st century we were thinking forward and set to welcome innovative contemporary architecture in a historic context. SAK: Who were some of the design consultants? These and other firms helped us raise the bar in terms of how to think forward but remain sensitive to the historic context of a city such as D.C., looking at models like Berlin and Paris, which have some of the same forces at work. So I have to say that my six years as deputy director of planning in D.C. were among the most fulfilling in my career to date, helping to create a new planning office in Washington D.C, and raising the level of design excellence and planning. Over that period of time, we developed and completed 44 plans, at the neighborhood scale and citywide and created a participatory planning process that actively engaged thousands of residents all across the city. On the Anacostia waterfront, the biggest result has been to create the Waterfront Corporation [2005]. Anacostia Waterfront Corporation has since begun to dispose of several parcels in their portfolio and launched several important capital improvement projects creating new open space amenities for the city. The corporation’s agenda focuses on implementing six distinct target area plans along the 11-mile stretch of waterfront encompassing the eastern third of the city. The target area plans are action-oriented with blueprints for land reclamation, creation of new residential and mixed-use neighborhoods, development programs and zoning recommendations, and public benefits including affordable housing; infrastructure and transit; and open space, recreation, and retail. Each plan also addressed environmental and sustainability standards to help promote reclamation of the Anacostia River. SAK: Where is the potential as you take over as the Newark, N.J., director of Community Development? SAK: What specific planning moves do you foresee in Newark? SAK: Talking to you I see no evidence that you underwent any kind of hardship in your career on account of being an African American and a woman. SAK: Do you remember any special race or gender based challenges at school or beyond? In going to the [Upper Manhattan] Empowerment Zone, of course, it’s night and day. It’s predominantly an organization of people of color—people of Latin descent and African Americans—so race was not an issue at all. And a great deal of our constituents were people of color because we were serving upper Manhattan, and that was very fulfilling for me. I started working more in the communities of color while at SOM. I think the firm saw a value in my ability to do work outside of downtown in a credible way because here they had a senior person of color who got respect and had a specific sensitivity to those communities. D.C. is where my color became much more important. With Mayor Williams starting a new administration in a city whose population is largely black, the diversity of our team was extremely important. Being an African-American and being a woman was very effective in my work going out into communities that had never before worked with a planning professional. Not that a majority person could not, but there's a perspective I bring that adds value to the process. You have to remember that in some of these communities, low-income neighborhoods in particular, the constituents coming out to meetings are African-American women—women who could be my grandmother, mother, or aunts. That’s going to be the issue for me in Newark as well.

On the way, he worked first as city planner in New York City’s department of city planning and later as an urban planning, design, and policy specialist before serving as director of the Northern Manhattan office of Manhattan Borough president and one-time mayoral candidate Ruth Messinger. Active in the American Planning Association (APA), he presided over the APA New York Chapter and, concerned about the status of minority practitioners, founded and chaired the Committee for African American and Latino Planners (later renamed the Committee for Ethnic and Cultural Diversity). Silver has spent most of his career in public service. But, between 1997 and 2001, he crossed to the private sector, where he was a project manager and partner in Abeles Phillips Preiss & Shapiro Inc., a visionary New York-based regional planning firm where he played a key part in the successful development and redevelopment of towns across New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut.

All together Silver has worked in more than 50 jurisdictions and is noted among his peers as a creative thinker and problem solver, having been in the midst of many cutting edge trends and visionary plans, such as Harlem on the River and the recovery of neighborhoods in Philadelphia and Washington. Following are his views on planning and racial topics in his profession, where, as of 2004, a tiny 2.7 percent of self-identified planners were African American, compared to 2.2 percent Latino/Hispanic, 2.9 percent Asian, and 0.4 percent Native American. The numbers are even lower when you count only certified planners. SAK: In a recent an article in the Raleigh News & Observer you were quoted as saying: “‘Over the next five years, we’re going to have a very different skyline, and it will be part of our city’s identity. We’re moving towards a twenty-first century skyline, from East to West, to have beautiful views.’” How can you control such a development? My department advises the City Planning Commission on telling the development and design communities how their project fits into our skyline. It’s part of our design process. We also have an Appearance Commission that weighs in on design. It’s something we tell developers and architects up front. We have so few skyscrapers that every new building warrants special attention, and we want to make sure that their building actually adds to the identity of the city. We now see the skyline spreading from the East side to the West side, so we have this postcard view. We ask the designers to photo-impose their building to see how it plays out in our skyline. SAK: From your time in New York, you mentioned the Harlem Renaissance. Why was this a satisfying endeavor? Now, I wasn’t the only one, but I was one of the very early spokespeople who talked about the untapped resource, the re-zonings that were available for some very attractive market-rate projects, and we started to turn the tide and get people thinking about Harlem as a place to do business. Over time, the real-estate market pushed people to Harlem, but my work in the 1990s played a role in Harlem’s Renaissance. The “Lift Every Voice” report was a landmark study that started to really change the thinking about Harlem and its redevelopment. SAK: You mentioned the Tower and Plaza Regulations in New York City. Follow-through came with a massive re-zoning of the Upper East Side to make sure that these new regulations were put in place. So the current zoning on the Upper East Side grew out of the work I undertook back in the ’90s to bring the Tower and Plaza Regulations to fruition in the Upper East Side. It was very fulfilling. SAK: Any hurdles, professional or personal, you have faced? Another hurdle is your credibility. Very often, if you’re in planning, they assume that if you’re an African American you’re very good at community participation and community facilitation, but forget that you have very strong zoning, analytical, and urban design skills. So I feel I broke apart from the pack because I exhibited those skills, which I developed over time. Even so, those skills are always brought into question. As minority professionals, we always have to prove our credibility. It’s something I no longer do, because it’s exhausting. I believe I now have a record of accomplishments so that I no longer have to prove myself. I had my first chance in the private sector. People hired me for my work, not for my color, although I’m sure I was hired whenever they needed a minority planner because they had a community of color to deal with. So my name was usually first on the list. But once I became part of the team, they soon realized I had far more skills than just my color. Those are obstacles I continue to deal with throughout my career. SAK: What about Raleigh, a Southern city? SAK: Can you explain? It’s just something that’s inbred in us, and while there are some who look at you for the value of what you bring to the table, there are others who still question that if you’re not white, then you’re good, but second-rate. I just don’t see that changing in the near future. I no longer pay attention to it. I’m going to be 47. I’m very confident in my skills and my ability, so I no longer worry about how people perceive me. I aim to be the very best I can regardless of what people perceive of me or my color. When I was younger, I worried about it. Now that I’m older, I have a record of accomplishments, so I don’t worry about proving myself to anyone any longer. SAK: What about younger generations? On the positive side, the APA Web site now has a section dedicated to diversity topics. A lot of us go out to high schools and undergraduate schools to talk about planning. It’s still an unknown profession to many people. This year we’re launching an Ambassadors Program. It will have people of color go out to those schools to talk about planning, talk about the contributions we have made to the profession, and to show: “Why is planning relevant to me?” Then we can tell them about the stories of other planners or other plans that have changed lives in Harlem or Bedford Stuyvesant or other communities. Such stories seem to relate a lot better than just having your typical land-use plan. They don’t connect to that. They relate better to stories, and stories about people. SAK: Do you agree with the idea of role models for design professionals of color? I try to sit down and be a role model for all the employees who work for me. In particular, I pay close attention to those employees of color. Because they need that feedback. SAK: How large is your department? What is the breakdown by African American, Hispanic, and white? SAK: You wrote me in an e-mail: “Planning is a bad word in some communities. It means gentrification, urban renewal, disenfranchisement, and social injustice.” Is this one reason for the low ratio of planners of color? Social injustice is still a common practice. People believe that there is a conscious effort to put all your unwanted facilities in less politically powerful communities. Gentrification is another issue, from their viewpoint—prices rise and the original families can no longer afford to live in the neighborhood. So I often have a tough time recruiting people, when they say planning is associated with so many bad things in their community—tough social issues, dumping grounds, public housing, putting roadways and highways in the wrong places; community facilities that you don’t want other places. That’s how they view planning. Of course I challenge them and say: “Well, you can make a difference and turn it around.” SAK: A final word? But we also work for a municipality, or we work for a private firm, so we’re stuck in this dilemma. Quite often, we’re put in a corner where we have to choose between our race and our profession. That’s a burden we believe our white counterparts do not have to deal with. I can tell you it can be an overwhelming dilemma at times. SAK: Professionals such yourself are in the best position to change the perceptions. |

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Three Views on the Prospects of Increasing Diversity in the Profession

› The Educators

› Young African American Women Sharpen Ties to Their Communities

Images:

Image 1: William A. Gilchrist, FAIA

Image 2: Olmsted plan for Birmingham

Image 3: Boutwell Auditorium

Image 4: Toni L. Griffin, AIA

Image 5: Anacostia River

Image 6: Mitchell Silver, PP, AICP

Image 7: Raleigh skyline

William A. Gilchrist, FAIA

William A. Gilchrist, FAIA A graduate of MIT’s schools of management and architecture, with a master’s degree from each, plus a degree from Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, Gilchrist’s educational focus has always been on public policy and the built environment, and one shapes the other. (His interests have ranged farther afield—he was among the first Aga Khan traveling fellows, ending up documenting the Swahili architecture of coastal Kenya.)

A graduate of MIT’s schools of management and architecture, with a master’s degree from each, plus a degree from Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, Gilchrist’s educational focus has always been on public policy and the built environment, and one shapes the other. (His interests have ranged farther afield—he was among the first Aga Khan traveling fellows, ending up documenting the Swahili architecture of coastal Kenya.) Currently Gilchrist serves on the departmental visiting committee of the MIT School of Architecture, the composition of which—equal parts African Americans, women, and whites—strikes him as a model of meritocracy. He was recently appointed to the international advisory committee of Carnegie Mellon University’s Remaking Cities Institute.

Currently Gilchrist serves on the departmental visiting committee of the MIT School of Architecture, the composition of which—equal parts African Americans, women, and whites—strikes him as a model of meritocracy. He was recently appointed to the international advisory committee of Carnegie Mellon University’s Remaking Cities Institute. Toni L. Griffin, AIA

Toni L. Griffin, AIA I first saw Griffin in action in April 2007 at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, where she moderated a one-day workshop sponsored by the John L. Loeb Fellowship Program. A former Loeb Fellow, she dealt expertly with a group of 16 articulate but often fractious participants, with a polite but unbending hand, moving everyone to the end of a heavy agenda. (GSA’s R. Steven Lewis, NOMA, AIA, a current Loeb Fellow, organized the session and is presently converting the conclusions into a specific multi-item action plan.)

I first saw Griffin in action in April 2007 at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, where she moderated a one-day workshop sponsored by the John L. Loeb Fellowship Program. A former Loeb Fellow, she dealt expertly with a group of 16 articulate but often fractious participants, with a polite but unbending hand, moving everyone to the end of a heavy agenda. (GSA’s R. Steven Lewis, NOMA, AIA, a current Loeb Fellow, organized the session and is presently converting the conclusions into a specific multi-item action plan.) Mitchell Silver, PP, AICP

Mitchell Silver, PP, AICP He then gained first hand experience running a public agency as business administrator of the North Jersey city of Irvington, overseeing day-to-day operations of a municipality that counted 8 departments and 600 employees. He served a brief term as deputy planning director of Washington, D.C., before moving to Raleigh.

He then gained first hand experience running a public agency as business administrator of the North Jersey city of Irvington, overseeing day-to-day operations of a municipality that counted 8 departments and 600 employees. He served a brief term as deputy planning director of Washington, D.C., before moving to Raleigh.