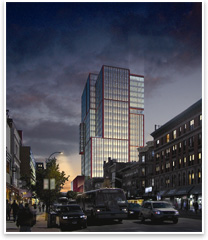

Putting the Pieces Together: Harlem Park Putting the Pieces Together: Harlem ParkHarlem Park isn’t just part of the neighborhood, it is the neighborhood How do you . . . respect the low-rise architecture of a place while building a high-rise tower that draws on local neighborhood forms? Summary: Swanke Hayden Connell Architect’s Harlem Park tower assembles the modular forms of the low-rise neighborhood it sits in to create a skyscraper that does not express its mass vertically. This is the first high-rise office tower to be built in Harlem in 30 years, and its developer hopes it will become a trademark branding building for the neighborhood. When design principal Roger Klein, AIA, was given the opportunity to show New York City’s Deputy Mayor of Economic Development and Rebuilding Dan Doctoroff how Harlem’s first high-rise tower to be built in 30 years would come together, he made sure to demonstrate its aesthetic roots in the existing neighborhood. He showed the deputy mayor a site model with wood blocks representing the surrounding 4- to 6-story neighboring low-rises. As he continued with his pitch, he stacked them together to form the 21-story, 600,000-square-foot structure that will be called Harlem Park, a (hopefully) iconic representation of the new explosion of development above 125th St.

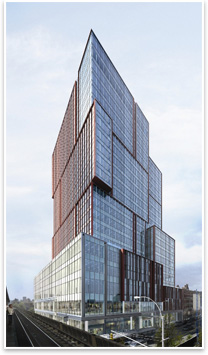

To its credit, Harlem Park looks as if it’s taken the still-gritty collection of motels, nail and hair salons, and fast food restaurants at 125th and Park Ave., dipped them in a terra-cotta finned glass curtain, and stacked them with no great care—allowing for jutting angles and exposed cantilevers. This looseness of form creates visual interest and helps disguise the building’s vertical mass, a requirement for respecting this historic neighborhood’s established architectural forms and traditions. Harlem Park doesn’t reach above its environment so much as it hunkers down into it, but it could never be called graceless or lumbering. “Instead of doing what architects usually do, which is to express the verticality of the tower, we tried to embrace the lower scale, squat volumes of the context and let the building harmonize with the adjacent buildings,” says Klein. Klein and his firm Swanke Hayden Connell Architects also used materials and textures to reference the surrounding neighborhood. Though the tower is sheathed in glass, reddish brown terra-cotta fins call to mind the nearby masonry buildings in an approach Klein calls “a reference to the materiality of the neighborhood, but in a contemporary and abstract language.” “It has more of an earthy quality to it,” he says.

“In my opinion, [the hotel] didn’t do all the things it should have done relative to making a statement about being in that area,” says Klein. “I think Enrique Norton is a good architect, but the building form could have been anywhere in the USA, or [anywhere] internationally.” Swanke Hayden Connell Architects’ consideration for Harlem’s architectural history should help bring in a specific type of tenant for Vornado Realty Trust, the site’s developer, Klein says. Renters interested in buying into Harlem’s neighborhood revitalization, attracted to its relative affordability within Manhattan, and drawn to its location next to a Metro-North commuter rail line stop are considered prime targets. This proximity to public rail line service did pose one technical challenge for Klein. Foundations needed to be aligned precisely with the adjacent station. Klein calls the proposed LEED Silver certification level a marketing “necessity” for Vornado, and Harlem Park will feature a 30 percent reduction in water use, solar reflective roofing, and preferred parking for car pools. Seventy five percent of construction debris will be recycled.

But will this burst of development change the character of Harlem irreversibly? Klein doesn’t think it has to. “I don’t think there’s any reason you can’t build in a sensitive way in these neighborhoods, even if you’re slightly larger in bulk than the adjacent neighborhood.” |

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› “Show You’re Green” Awards Go to Eight Sustainable—and Affordable—Projects

› St. Louis Residential Tower Design Unveiled

› The Next World’s Tallest Building? It’s Anybody’s Guess

Photos:

1. Harlem Parks makes a bold statement against the skyline without overwhelming the neighborhood.

2. The building’s platform respects the low-rise nature of the streetscape.

3. Can the Harlem Parks revitalize 125th St. and Park Ave. without changing the neighborhood forever?

4. Looking east down 125th Street.