|

The Next World’s Tallest Building? It’s Anybody’s Guess But the Third World is rising to the top Summary: The event horizon of high-rise development in emerging nations is rapidly accelerating to an unpredictable pace. In such places, where construction is cheap and real estate on par with top American markets, builders can afford to splurge on ambitious design and be appropriately rewarded. This boom is capturing the same desires and aspirations that fueled America’s 20th century skyscraper dominance, albeit with an emphasis on personal ownership and mixed-use design.

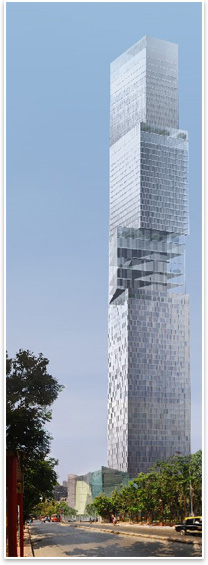

The recent skyward explosion of high-rise development in developing nations (China, India, Dubai) has taken America’s previously undisputed mantle of builder of the best and tallest. Certainly, the urge to build to the stars is primordial. But only recently has what author and New York City-based architect James Sanders calls the “force-multiplier” of the American media translated this urge into a symbol of modernity itself through its invasive marketing of modern cityscapes to the rest of the world. “The meaning of these buildings got transferred from what they were to being a symbol of what it means to be a modern civilization,” he says. “[Developing nations] are sort of desperate to prove that they are players and powers in the global contemporary world.” One hundred sixty-story cloud-piercers don’t get built anywhere without deep pockets willing to take risks, and developing nations have been thickening this capitalist-investor class. China’s GDP has multiplied by a factor of nearly 10 in the past 15 years. Dubai’s population has doubled since 1993. Mixed-use high rises, your own piece of the sky FXFowle is one such international player. They established a representative office in Dubai about a year ago. Peter Weingarten, AIA, FXFowle’s director of international architecture, says many of his clients are interested in the energy-efficient aspects of high-density vertical development. One such project is FXFowle’s India Tower in Mumbai, which uses a solar chimney to generate electricity, provides on-site wastewater reclamation, and is LEED®-Gold certified. Without the current climate of rampant and volatile high-rise development, the silver 85-story tower would be universally recognized as India’s next tallest building, but now, Weingarten says, not even this visionary project can claim the subcontinent with any great certainty. Weingarten’s vision of India Tower’s transformative potential is emblematic of developers in many emerging nations. “It will have a much more intangible effect than just another big building, and then it will spur more development around it,” he says. “It becomes a magnet and a center, and if enough of these dots start to get created and they start to become connected into a network, you can really start to see some dramatic changes in the landscape of Mumbai and India.”

No glut of projects It’s a new situation for the world’s tallest buildings to be available for residential purchase, but many new super-tall developments are planned for mixed-use and not traditional commercial office space. Sanders says this transition is fueled by the growing globe-trotting elite that is hungry for the affectation of being able to describe their address as “the tallest building in the world.” For them, this is a chance literally to buy into to the symbolic value of the modern skyscraper. In Dubai and other cities where high-rise development races ahead of everything else, mixed use is the best way to create neighborhoods that are socially sustainable and livable. “In Dubai, where [skyscrapers] are coming out of the ground and the follow-up development is a couple of years behind, [developers] need to create a synergy in this place now,” says Weingarten. “The way they can do that is by creating a mixed-use community.”

In a counterintuitive way, this race to the top might negate the fundamental attraction of building the tallest structure. If “the tallest building in the world” changes with the tides, Sanders wonders, “What does it mean anymore if no one can keep up with it?” |

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

Photos:

Image 1: FXFowle’s India Tower is likely to be one of the world’s tallest and greenest buildings.

Image 2: The Shanghai World Financial Center will soon dethrone its next-door neighbor, the Jin Mao Tower, as China’s tallest building.

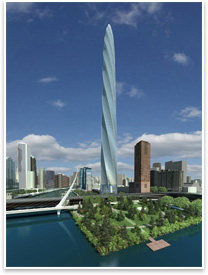

Image 3: Santiago Calatrava’s Chicago Spire is America’s applicant for the world’s next tallest building.