|

Fitter. Happier. Better. Greener. Science shows sustainable design does more than help the Earth; it makes you feel better, too.

As an architecture student in 1961 at the University of Kansas, Bob Berkebile, FAIA, began examining how color, humidity, temperature, and other environmental factors affected patients at a local mental health clinic. This study was his attempt to figure out how and why different places made him feel differently; why awe and reverence washed over him in a cathedral, or perhaps why a greenhouse bathed in sunlight leaves people feeling refreshed and rejuvenated. Berkebile learned a few things about how the built environment works on people’s psyche, and these revelations were on his mind when he helped found the AIA’s Committee on the Environment (COTE) and the United States Green Building Council (USGBC).

The task Loftness says more long-term, single-variable research is needed. “An area of research that is definitely needed is to be able to show causal relationships to each of these variables and outcomes,” she says. “What we have now is not science,” says Berkebile. “What we have now is anecdotal.”

Any such work will be built on studies already completed by Carnegie Mellon, the Rocky Mountain Institute, and Berkeley’s Center for the Built Environment. A study in North Carolina revealed that children in schools with more natural day lighting scored 5 percent better on standardized tests than children in normal, comparable buildings. The National Academy of Sciences commissioned a study that indicated that teacher productivity and student learning, as measured by absenteeism, is affected by indoor air quality. A 2003 study penned by Loftness measured how certain green building features increase worker productivity. It recorded a 3-18 percent gain in buildings with day lighting, a 0.4-7.5 percent gain in places with natural ventilation and access to the outdoors, and a 0.2-3 percent gain in buildings with individual temperature controls. Though these single-digit increases seem modest, commercial and institutional buildings spend 88 percent of their budgets on labor costs, according to a report by the Canada Green Building Council, so the value of any more productivity that can be squeezed from employees is disproportionately large. “Clients are beginning to understand in a much more robust way how very valuable these intangibles are in terms of [the] bottom line, mostly because they know that people are their greatest cost,” says Kira Gould, Assoc. AIA, the current chair of the AIA COTE and director of communications at William McDonough + Partners, a leader in sustainable design. Dan Walker knew about the social benefits of environmentally friendly design before he started planning the Missouri Department of Natural Resources’ new Lewis and Clark State Office Building in Jefferson City. Designed by Berkebile’s Kansas City, Mo.-based BNIM Architects, the Lewis and Clark Building is certified as LEED Platinum and features personal airflow controls, daylight that reaches 75 percent of the building, and zero water runoff. Walker, the building’s project manager, says that since it came online in March of 2005, two productivity studies have indicated that the environment has made people more effective employees.

Harvard biologist Edward Wilson coined the term biophilia in 1984 to describe humanity’s innate attraction to nature, and this concept has been adapted to examine how the built environment can satisfy this desire. Biophilic design posits that humans have evolved to be a part of nature, but the emergence of the built environment and Western philosophy’s staunch belief in man’s subordination of nature has systematically altered and destroyed this relationship. To realign us with this aspect of our evolution, Wilson and Berkebile’s ideas suggest that integrating real or simulated natural elements into buildings will improve people’s well-being. This will require a research effort that simultaneously looks into the past and the future, studying both how emerging technologies can elicit psychological responses in the built environment, as well as reconstructing the idealized primeval environment that our minds yearn for. But Berkebile also wonders if it might be too late for this. Maybe the dank office cubicle is man’s natural habitat now, and we’re chasing our evolutionary tail, forever one step behind the ancestral ideal we’re attempting to recreate. “We are evolving as a culture and as human beings, and maybe [we] have evolved away from some of that capacity we once had,” he says. “We were designed as an organism to be integrated with nature, and as we have separated ourselves, we have modified the system in a negative way, and the more we can do to restore that connection the better off we’ll be.” |

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

Recent related

› Biophilic Design Connects Humans with Nature

› Architecture and the Brain: A New Knowledge Base from Neuroscience by John P. Eberhard, FAIA (review)

Images:

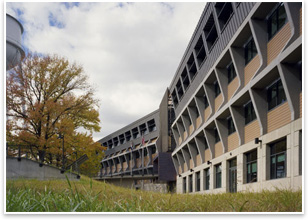

1. The Global Ecology Research Center, Stanford, Calif., by EHDD Architects, a 2007 COTE Top Ten Green Buildings Award recipient, employs a Night Sky radiant cooling system, which demonstrates the same principles of radiant heat loss to deep space that the researchers are investigating.

2. Carnegie-Mellon’s Robert L. Preger Intelligent Workplace is a living laboratory allows for study of high-performance workplaces, including lighting and HVAC.

3. The LEED ® Platinum-rated Missouri Department of Natural Resources Lewis and Clark State Office Building, Jefferson City, by BNIM.

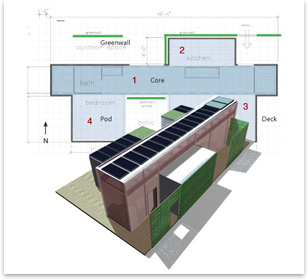

4. Carnegie-Mellon also is one of 20 universities taking part in the 2007 Solar Decathlon.