| Discovering African Identity in African-American Architecture: Part I

How do you . . . recognize elements of architectural identity in work by a particular racial or ethnic group? Is it even possible? Summary: African-American architects constantly ask themselves whether there is such a thing as African identity in their architecture. In other words, would an observer, architecturally trained or not, spot/observe any African traits in the architect’s use of materials, siting, detailing, ornament, forms, and space flow that might identify a design as the work of an African-American architect?

Opposed are those who contend the argument lacks logic in the face of practical reality. For example:

This month’s episode in the AIArchitect’s diversity series offers answers to these divergent views, relying on some of America’s most resourceful African-American practitioners and scholars. Due to the breadth of the topic, you’ll see it in two parts. Look for part II in August. |

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

home

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Doer’s Profile: Curtis Moody, FAIA

› Corporate and Public Architects: Seeing from the Client’s Side

› Architects Engaged with Civic Leadership

Look for “Discovering African Identity in African-American Architecture: Part II” next month.

Did you know . . .

500 new hotels. In a move that places African Americans in the patronage driver’s seat, the National Association of Black Hotel Owners, Operators, and Developers plans to build 500 new African American owned hotels by the end of 2010. NABHOOD hopes to open 122 of them this year, bringing the national total to 289. There are reportedly some 50,000 hotels in the U.S., so the present ratio of black-owned hotels isn't large, but the initiative is a strong upbeat sign. Let us see how many of the design commissions will go to black architects. Seldom has there been a greater opportunity.

African-British architect David Adjaye keeps drawing more limelight as a major exhibit of his work opens July 18 at the Studio Museum of Harlem. The show tracks 10 of his projects from start to finish. Adjaye has lectured in New York City, and the Harvard Graduate Scholl of Design this year had a show of his work that took up the entire spacious entrance hall.

Harlem’s first tall office building since 1973 is to rise at 125th Street and Park Avenue. Vornado Realty Trust has chosen Swanke Hayden Connell Architects, a large Manhattan-based majority-owned firm, as the architect. “We hope they are successful in getting tenants,” Harlem Community Development Corporation president Curtis Archer told Architectural Record. No word whether an African-American architect was considered.

AIA Seattle’s diversity scholarship has been named after outgoing longtime Executive Director Marga Rose Hancock, Hon AIA.

Boston Architectural Center has named a full-time director of Human Resources and Diversity. Michael James was previously chief of Equal Opportunity and Diversity at Massachusetts Bay Community Railroad.

Images

Image 1: “Builders #2,” by Jacob Lawrence, 1968. Photo: The Jacob and Gwendolyn Lawrence Foundation/Art Resource, N.Y.

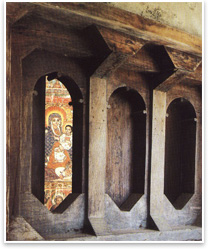

Image 2: Detail of Triforate windows at the Church of Narga Sellase in Ethiopia. Photo courtesy M. David Lee, FAIA.

Image 3: Northeastern University’s John D. O’Bryant African-American Institute main façade, by Stull and Lee Architects, is based on the Narga Sellase form. Photo by M. David Lee, FAIA.