| DIVERSITY Corporate and Public Architects: Seeing from the Client’s Side Summary: Architects who work in-house for agencies, foundations, and corporations work closely with design firms not as designers themselves but as procurers of design services and the owner’s rep during design, construction, and occupation. This month, Stephen Kliment, FAIA, profiles two African-American architects who have mastered that role, Andrew Thompson, AIA, and Ricardo C. Herring, FAIA. Below is a synopsis of the article. Follow this link for the full text. No matter whether the organization the in-house architect works for is strictly a public agency, a nonprofit organization, or a pure private for-profit corporation, all have earmarks in common. First, the corporate or public agency architect recognizes the task typically is to select design architects but not do the design, and to prepare the program, budget, and schedule but have the architect execute them. The in-house architect must therefore possess a strong sense of how buildings come together and what it takes to operate them; how to talk the architect's language but not try to spoon-feed design solutions; how to act as liaison with the internal branches, divisions, and departments in the company or agency; and, in sum, how to fashion the project team and make sure it functions as it should. Some professionals on the corporate and public side see little new construction. Their job is to make sure the facility or facilities function for their stated purpose. Both subjects of this ninth episode in the diversity series work for large organizations linked to health care. Andrew Thompson, AIA, is chief architect at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York City. Ricardo C. Herring, FAIA, is acting chief of the Policy Branch, Division of Policy and Program Assessment at the National Institutes of Health Office of Research Facilities, Bethesda, Md. Both architects are African-American, and each has risen to a level of prestige that any architect of whatever color would envy. But both had hurdles to overcome…

When he first came to Sloan-Kettering, Thompson helped develop and now takes advantage of a highly detailed archive of databases and drawings—one of the most detailed of any hospital in New York. The archives comprise all Sloan-Kettering buildings on site from the time they were first built, including all modifications. “This way we can always keep on top of the status of any construction and help our maintenance staff on day-to-day issues,” Thompson said in an interview. But the path wasn’t easy, as we shall see in the full-text interview article.

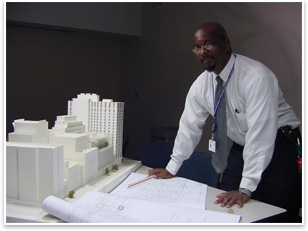

Early in 2007, Herring returned to NIH after a two-year stint in the Office for Facilities Management and Policy in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (NIH’s parent agency). As a senior facilities program manager, his job was to develop and carry out department-wide policies that shaped day-to-day facility management and operations for several HHS agencies such as the Centers for Disease Control, Food and Drug Administration, Indian Health Service, and NIH. Herring joined NIH in 1989 as senior architect and resident architectural expert in the Facilities Planning and Programming Branch at the Division of Engineering Services. He also served as its historic preservation officer. Prior to NIH, Herring was a supervisory architect with the U.S. Department of Labor in charge of planning, design, rehabilitation, and construction of Job Corps Facilities nationwide. Herring has 12 years in the private sector, including 5 years as a project manager with McDonald & Williams/DeLeuw Cather Parsons on the Northeast Corridor Improvement Program, where he was in charge of programming and designing Amtrak maintenance facilities from Washington to Boston. Born and raised in Washington, D.C., where he attended D.C. public schools, Herring earned a BArch from Howard University in 1973. He is a registered architect in two states and the District of Columbia. The basis for his AIA Fellowship election in 2001 was for “advancing the living standards of the American people by setting architectural design guidelines for state-of-the-art biomedical research facilities that are vital to the health care of the nation.” In the full-text, article Herring names three career accomplishments he’s most proud of, and why. |

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Architects Engaged with Civic Leadership

The topic of next month’s diversity column is Afrocentric design and America’s black architect. Is Afrocentrism an idea whose time has passed, or one whose time is yet to come? Stay tuned.

Did you know…

J. Yolande Daniels, partner in the Long Island City, N.Y., firm SU MO Architecture, recently reported on the opening of the Museum of Contemporary African Diaspora Art (aka MOCADA). Located in Fort Green, Brooklyn, MOCADA occupies the street-level floor of an old 10-story brick office structure. The design concept of the museum is a play on the world’s 24 time zones, symbolizing the African Diaspora worldwide and expressed architecturally through a powerful series of 3-D wooden slat structures. The long narrow space is lighted through a set of ingenious overhead light boxes.

Andrew Thompson

Andrew Thompson