Let them Eat Cake—But Not From the Menu

BHSL Design’s restaurant overthrows

the tyranny of the menu and puts the diners in power

by Zach Mortice

Assistant Editor

Summary: Hong

Kong-based BHSL Design’s menuless restaurant attempts to reconnect

diners with primeval, naturalistic patterns of food consumption by

presenting patrons with a field of hydroponic and aeroponically grown

fruits and vegetables to be picked and prepared at their discretion.

Its forward-looking design co-opts technology in a counter-intuitive

effort to make food preparation more arduous and self-aware.

For too long, humanity has been conscripted under the jackboot of the menu. For too long, humanity has been conscripted under the jackboot of the menu.

This seemingly innocuous document has managed to divorce mankind from his relationship with food, while straitjacketing the culinary choices of a race of creatures that could previously eat anything in any manner that the land could provide. Scarcely an eyebrow has been raised and now their dominance is complete. We scarcely know what do to in a restaurant without one. But no more. The menu’s free pass is over.

Husband and wife team Belinda Ho, AIA, and Li Shiqiao’s menuless restaurant design is a call to action to usurp what they call “an epitome of humanity’s alienation from the sources of food.”

“You eat A, B, C, or D. It’s a form of oppression,” Shiqiao says with a chuckle that slyly winks at this hyperbole.

Quintessentially human

Ho and Shiqiao’s project began life as an entry into a Japanese glass company’s competition to design a restaurant in a rural area. Ho says they began by looking at a restaurant’s fundamental starting point—the menu. They found ways to revise it and perhaps reason to abolish it. The menu, they say, is dictatorial. Somehow, the industrialization of food has both made it easier to make and thus more widely available, yet still limited the composition and preparation choices an individual has at a given location. In addition to being despotic, menus are also secretive.

The architects contend that the menu takes people away from the primeval and quintessentially human understanding of how food is harvested and prepared. At a restaurant (and at a grocery store), the kitchen becomes a “black box” where food is assembled from unknown components and presented wholly prepared, fostering the illusion that food has no connection to the natural world. Perhaps Ho and Shiqiao’s most pressing concern is communal. When diners order from a menu, they miss out on an experience that helped to bond ancient civilizations the world over—the communal and social cooperation required for food preparation. The architects contend that the menu takes people away from the primeval and quintessentially human understanding of how food is harvested and prepared. At a restaurant (and at a grocery store), the kitchen becomes a “black box” where food is assembled from unknown components and presented wholly prepared, fostering the illusion that food has no connection to the natural world. Perhaps Ho and Shiqiao’s most pressing concern is communal. When diners order from a menu, they miss out on an experience that helped to bond ancient civilizations the world over—the communal and social cooperation required for food preparation.

Come for the experience, stay for the food

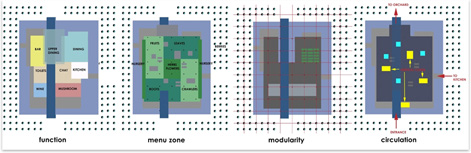

Despite the heated rhetoric, BHSL’s design does feature a “menu” of

sorts. Their restaurant recasts the menu as a vast hydroponic and

aeroponic field where diners can pick the fruits and vegetables they

want to eat and then prepare them any way they wish. This journey

begins with diners entering the restaurant through a rectangular

glass tunnel. They then walk up a slowly sloping series of modular

beds, each 1.6 x 2 meters (5.25 x 6.5 feet) with walkways between

each pair of beds. Here, visitors pick all the ingredients for their

meals. Stationed throughout this “menu” are cooking information

stations where a chef advises patrons on ways to prepare their food.

Here too, the restaurant subverts the typically autocratic process

of ordering food. The relationship between the diner and the chef

changes from an anonymous taking of orders to a collaborative partnership

where, as Shiqiao says, the chef is the “enabler.” The

diner may choose to cook their own food, or let a chef do it, but

the composition and preparation will be in the patron’s hands.

The fruits and vegetables in the greenhouse “menu” grow in hydroponic and aeroponic modular beds that can be rapidly replaced as they are emptied and picked. Ho envisions an interior gondola system the runs on tracks along the glass roof that can deposit new food beds into the proper place. Hydroponics grow plants by suspending their roots in a nutrient-infused water solution, and aeroponics aerates such a solution and sprays it on plant roots. These types of farms (Ho and Shiqiao visited several before designing the restaurant) offer growers more control over plant growth and health and also eliminate weeds. Because all the ingredients for patrons’ meals are grown on-site (reducing its carbon footprint and offering some benefits of a green roof) the climate, temperature, and geography of the restaurant play much larger roles in the experience of eating, again forging a more naturalistic relationship with the land and its food. (Such a restaurant in Florida is more likely to supply oranges than cabbage.) The fruits and vegetables in the greenhouse “menu” grow in hydroponic and aeroponic modular beds that can be rapidly replaced as they are emptied and picked. Ho envisions an interior gondola system the runs on tracks along the glass roof that can deposit new food beds into the proper place. Hydroponics grow plants by suspending their roots in a nutrient-infused water solution, and aeroponics aerates such a solution and sprays it on plant roots. These types of farms (Ho and Shiqiao visited several before designing the restaurant) offer growers more control over plant growth and health and also eliminate weeds. Because all the ingredients for patrons’ meals are grown on-site (reducing its carbon footprint and offering some benefits of a green roof) the climate, temperature, and geography of the restaurant play much larger roles in the experience of eating, again forging a more naturalistic relationship with the land and its food. (Such a restaurant in Florida is more likely to supply oranges than cabbage.)

Ho says she would be open to expanding this concept to include live animals, but her most important concern isn’t whether what ends up on the plate was ever alive or not: it’s the experience of putting that plate together.

“[I imagine it] as a day outing or gathering where people interact instead of just staying at home [and] opening a box where you don’t ever talk to anyone about what you’re eating and you don’t know what you’re eating,” she says via phone from her Hong Kong office.

BHSL’s design strives to make this type of casual interaction

as intuitive as possible. Shiqiao suggests that the “menu” should

be aesthetically pleasing enough on its own to merit a peaceful stroll

without so much as plucking a blackberry. The glass-sheathed “menu” is

open and airy, with vertical glass shafts that contain stairs and

run down to the lower two dining area floors and kitchen. The second

floor dining area is the smaller of the two and is partially cantilevered

on its north end. The larger dining area is on the first floor and

is adjacent to a pre-cooking discussion area, where diners finalize

their plans, and a kitchen where they prepare their food. In both

dining areas, no maitre d' tells anyone where to sit, and the premises

are fresh and light-saturated to encourage interaction and discussion.

Many of the interior walls are transparent as well. Though the restaurant

may be quite large (approximately 9,000 square feet) and expensive

by conventional standards, Ho says it’s completely buildable,

and the experience it offers is what will determine its value. “I

envision a family of three or four to be spending the whole morning

there,” she says. “If you divide that time over the amount

of money you pay, it’s really quite affordable.”

Back to the future

The restaurant’s transparent glass shell and the arcing space

trusses that support it look bluntly futuristic, and functionally

it is progressive in its approach to growing food aeroponically.

But BHSL’s menuless restaurant isn’t interested in pushing

food into any new uncharted territory. Its goal is to restore the

natural order of food preparation and consumption that was disturbed

by the industrialization of food and the division of labor in society. “We’re

consciously making a point,” Shiqiao says of his design’s

juxtaposition of old concept and new design. “We’re not

trying to be romantic and [go] back to medieval villages and ways

of living that are probably not quite possible in the way we have

shaped our lives today.”

It’s a rare instance of technology working to make our lives slower and more laborious; to make us more self-conscious of our actions and our relationships with the land. And, as Ho and Shiqiao hope, in some small way, to make us a bit more human. |