| Diversity The Educators

The challenge is not even at heart one of finances. Majority schools are raising money to provide more scholarships for African-American students. Yet far more productive over the long haul in graduating a higher rate of black students is to find and admit a significant enough group to establish what Max Bond, Sharon Sutton, and others call a “cohort” whose members support each other. On a par with slim student enrollments is the need to attract and promote black architecture faculty at the majority schools. This is on the premise that a higher black faculty ratio will provide black students a close up—for those who believe in the concept—of real, in-the-flesh role models. (The ratio of full-time black faculty has declined from 6.2 percent of the total to 5.2 percent between 1997 and 2003). The long-term solution for getting more black faculty into the architecture schools is heavy recruitment, networking, and going out into the firms and the AIA committees with the message that teaching is an important and intellectually rewarding career option. Black architects and architecture graduates for their part should look more openly at a teaching career, instead of focusing single-mindedly on private practice. It is a two-way street: deans cannot be expected to create black teachers when there is no interest. This month’s column features profiles of three prominent African-American educators—Professor Sharon Sutton at the University of Washington in Seattle, Professor Garrison McNeil at the City College of New York, and President Ted Landsmark of the Boston Architectural College. Each brings to the scene a unique insight.

Beginning as an instructor at Columbia (co-teaching with Max Bond, FAIA), he moved to CCNY on a tenure track within two years. In practice as well for 30 years, McNeil has seen the difficulty of working within a system that has long kept black architects “above 110th Street.” The solution, he says, is in developing networks, working with U.S.-born black students and young architects to overcome what they have internalized over the years, and encouraging patrons—particularly wealthy black patrons—to recognize the talent and cultural insight of their fellow African Americans who are architects.

Although hopeful of the future of diversity in the profession, as the population itself becomes more diverse, she targets the low earning power, social irrelevance, and regressive employment practices among all architects as a deterrent to minorities entering the profession. She looks back on her own experience, including an exemplary era of forward-moving institutional practices of the late 1960s and early ’70s, for inspiration. And she sees specialization as a key element to making architects professionally relevant, especially in the realm of environmental expertise. “Things can only improve,” she says.

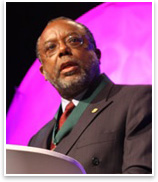

“Until conversations engage a wider range of participants, including people outside the architecture profession and the architecture schools, we won't make much significant progress,” Landsmark says. “But until the moment we begin to talk more seriously with high schools, community colleges, and suppliers of architectural products, such as Home Depot, Wal-Mart, and Loews, it's unlikely that we'll see much substantial change.” That, he says, will be how architecture reaches the mainstream awareness among the public enjoyed by professions such as medicine and law. Further, he says, a key to getting more diversity in the faculty of architecture schools, where there are few black doctoral graduates, is to turn to advanced-degree candidates from the related professions. An example of the difficult situation of drawing and keeping black architects in academia, he points out, is the difficulty among Historic Black College and Universities of maintaining architecture programs. Tuskegee Institute, for example—historically one of the top educators of black architects—has recently lost its NAAB accreditation. Mostly because of a lack of the institution’s interest in the program, graduates of that venerated program are not eligible for state licensure. It is a time for other institutions and professionals to pay heed and offer help, he says. “This is a moment when we need to take a really hard look at what we've done in the past and how it has failed,” Landsmark concludes overall, “and then adopt programs that are unified and focused on achieving real results.” For more in-depth profiles of these educators, see the full-text version of this article. |

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Community-conscious Architects Who Are African-American Women

› Making Partner in the Majority-Owned Practice

› Three Contemporary Star Architects

› The Trailblazers

› Diversity: What the Numbers Tell Us

Read the full-text version of this article.

See the September 2007 diversity column for more about black patronage, plus profiles of prominent black patrons.

Sutton photo courtesy of Dr. Sharon Sutton, FAIA

Did you know . . . ?

Museum for African Art (Act II). Last month we commented in this column on the selection of Robert A. M. Stern, FAIA, as design architect and Schuman Lichtenstein Claman & Efron (SLCE) as production architects to design the new Museum for African Art in East Harlem. Bob Stern, of course, is an excellent architect. But if ever there had been an opportunity to tap a black architect (program, location, etc.) this was it. The reaction to protests was a stony silence—until, that is, the week of March 12, when Raymond Plumey, FAIA, a New York-based Latino architect and a former chair of the national AIA Diversity Committee, reacted and was able to get New York State Senator Bill Perkins to agree to meet with interested parties to discuss the selection and the lack of professional minority participation. The meeting is slated for March 30. Stay tuned. –SAK

Academe is ramping up diversity activity. Harvard GSD Loeb Fellow R Steven Lewis, AIA, NOMA, has planned a full-day meeting for April 20 to tackle diversity. At MIT, March 16-17 saw attendees focusing on the theme “Architecture Race Academe: The Black Architect’s Journey.” Another meeting is scheduled for March 30 and 31 at the University of Pennsylvania, and, on October 27, alumni day at Columbia University’s school of architecture planning and preservation, Dr. Sharon Sutton, professor of architecture at the University of Washington, (and subject of one of this week's three profiles), is assembling the large block or “cohort” of Black and Puerto Rican students who attended the school in the heyday of minority recruitment between 1964 and 1974. We welcome this spate of activity and hope as always that the long-term results will justify the talks.

Died: Frank M. Snowden Jr., 95. Dr. Snowden was a leading authority on black people of the ancient world and their lives. A historian who taught for 50 years at Howard University, he argued that racial prejudice was largely absent in Greek and Roman antiquity. Notes Margalit Fox in an obit in the New York Times: “Whites in the ancient world rarely equated blackness with subordination, Dr. Snowden argued, because the black people they encountered were rarely slaves (most slaves in the Roman Empire … were white). Instead they met blacks who were warriors, statesmen, and mercenaries.”

Diversity: More large law firms manage to walk the walk. In a survey conducted by the firm Altman Weil, aided by the Washington,DC-based Minority Corporate Counsel Association, of the 72 responding firms, 50 percent have a designated diversity manager, up from 5.4 percent one year ago. Diversity managers participate in lawyer and staff hiring, professional development, compensation, and partner review.

Correction. June Grant, subject of one of last month’s two African-American women architect profiles, reminds us that the café she is building as part of her storefront Oakland office is an act of investment in a better community and the exploration of ideas. She sees profit as not only a quantitative but also a qualitative reward.

Central to the advancement of the African-American architect is the architecture school. The architecture school is the environment where black students first come upon professional attitudes that they’ll encounter later on when in practice. It is also a venue where blacks are minimally represented. As noted in the first column in this series, the number of fulltime black students at the accredited schools declined from 1,332 to 1,268 between 1991 and 2003, and the number of graduates dropped from 214 to 156 in the same period.

Central to the advancement of the African-American architect is the architecture school. The architecture school is the environment where black students first come upon professional attitudes that they’ll encounter later on when in practice. It is also a venue where blacks are minimally represented. As noted in the first column in this series, the number of fulltime black students at the accredited schools declined from 1,332 to 1,268 between 1991 and 2003, and the number of graduates dropped from 214 to 156 in the same period. William Garrison McNeil, RA, NOMA

William Garrison McNeil, RA, NOMA Dr. Sharon E. Sutton, FAIA

Dr. Sharon E. Sutton, FAIA Ted Landsmark, Assoc. AIA, NOMA

Ted Landsmark, Assoc. AIA, NOMA