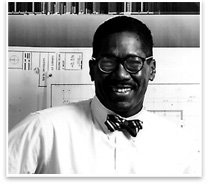

DIVERSITY DIVERSITYMaking Partner in the Majority-Owned Practice Summary: Ralph T. Jackson, FAIA, is a partner with Shepley Bulfinch Richardson & Abbott, a Boston firm named for a descendant of Charles Bulfinch, architect of the Massachusetts State House, and the renowned Henry Hobson Richardson. Jackson, born in the South, moved north as a child, survived a bumpy period of schooling, and worked in a professional environment where his color was at first mistrusted. By virtue of an influential mentor-partner at Shepley Bulfinch and his own personality—which includes a singular talent for comprehending the client’s real motivation in building—Jackson worked his way to principal after 15 years in the firm that he joined 31 years ago.

Early hurdles

He came to Shepley Bulfinch “because I have what I considered a talent, and that was working on buildings for clients of a certain kind. I had none of the connections that go with being able to pursue a life in that world. So I needed an organizational setting that provided me with the access and then to create a role for myself in that context. And when I first came in [1975], I'm certain the assumption was that I would be a technical person.” That promised a limited future in the firm. What overturned that notion was the legendary Jean-Paul Carlhian, FAIA, giving Jackson a research project requiring an analytical approach, which he delivered. Jackson joined the firm, and Carlhian became his mentor.

For a firm that lacks a distinctive formal style—and few firms that are run as a multi-principal practice nowadays have one—it is rare for projects to clearly bear one designer’s stamp. In Jackson’s case, African identity is undetectable to most eyes. Moreover, while Jackson’s clients like design awards, it’s not their primary concern. Instead, his office tower in the World Trade Center complex in Boston’s Seaport District reflects his passionate belief that buildings respond to context. Perhaps that building embodies elements of Jackson’s own journey: the tower blends in, it is made of traditional materials treated with a deep commitment to material quality, it has a sense of permanence. It also incorporates the client’s values. So does Bates Hall (the upgraded reading room at Boston Public Library), the library at Fordham University, the Worcester Courthouse, and the Georgetown Law Center. His design for the University of Denver Law School has made it into the country’s first LEED® Gold certified law school.

|

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Three Contemporary Star Architects

› The Trailblazers

› Diversity: What the Numbers Tell Us

Next month: challenges and successes of the woman minority architect.

Images:

Image 1: Ralph T. Jackson, FAIA. Photo by Larry Lawfer

Image 2: “Builders-19 Men,” by Jacob Lawrence, 1979. Photo: The Jacob and Gwendolyn Lawrence Foundation/Art Resource, N.Y.

A full-text, printer-friendly PDF version of this article is available.