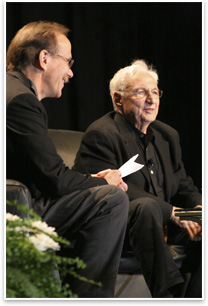

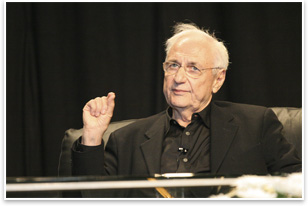

Gehry Talks About Architecture and the Mind at Neuroscience Conference

Gehry’s presentation drew an estimated crowd of 7,000. “For a non-scientist to attract that many people speaks to the success of Gehry’s lecture,” Society for Neuroscience President Stephen Heinemann said. “This is an experimental series looking at the top creative people in their field. We want to look at the best and get a feel for what our minds can do.”

“I am always insecure. I am never in my mind guaranteed that it will be a good building,” Gehry said. “When I started in this profession, it was fraught with rules of things you shouldn’t do and can’t do, and that veil was lifted from my life by Dr. [Milton] Wexler [therapist] who persuaded me … to bring myself to it, to be myself.” “I am never in my mind guaranteed that it will be a good building.” “Informed intuition” Similar to a scientist’s approach towards experimental design, Gehry’s design decisions are not arbitrary and are grounded in knowledge about variables such as pro forma, budget, environment, and scale: “It is an informed intuition because I know the functional issues backwards and forwards,” he said. “It is an informed intuition because I know the functional issues backwards and forwards.” In this discussion of his creative process, Gehry’s words resonated with many neuroscientists in the room. “Several neuroscientists came away talking about some of the terms Gehry coined such as ‘informed intuition,’” commented Society for Neuroscience Executive Director Marty Saggese. Gehry expressed reservation about translational applications between neuroscience and architecture, asserting that it might result in a “rule book” for the design profession. Responding to these concerns, Dr. Fred H. Gage, a Salk Institute neuroscientist and past president of the Academy of the Neuroscience for Architecture, explained: “We see the information that neuroscience will bring to architecture as offering another layer of knowledge to inform intuition, not adding a set of rules or barriers during the design process.”

Magic Trick … or cognitive gift? The neuroscientists present might speculate otherwise… a cognitive trick, perhaps. |

||

Copyright 2006 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

Recent related

› Programming Blog Offers Information-sharing Loop in Pre-design Stage and Beyond

› The Neuroscience and Architecture of Time

› Health-Care Facilities and Neuroscience Knowledge

Photo © 2006, Society for Neuroscience. Photos by Joe Shymanski.

Relevant Conference Topics

• Environmental Enrichment: effects on behavior, neural structure and disease

• Sensorimotor Integration and environmental adaptation across the life-cycle

• Relationship of auditory cortex to context: more than just processing

acoustic information

• Effects of environmental context on drug-addiction related behaviors

• Spatial learning, spatial memory and cognitive maps

• Multisensory Integration: Cross-Modal Processing

• Visual cortex: Orientation and color.

For more information about the conference and the Society for Neuroscience, visit their Web site.

Learn more about architecture and neuroscience on the Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture’s Web site.

Summary:

Summary: A glimpse into Gehry’s mind

A glimpse into Gehry’s mind Sharing cross-discipline knowledge

Sharing cross-discipline knowledge