Hospital Design as a Primary Tool for Healing

Patient-centered design is a concept now embraced by clients

by Gideon Fink Shapiro

Summary: New studies are linking the architecture of healthcare facilities to the quality of patient care, operational efficiency, and caregiver performance. In anticipation of the fall 2009 conference of the Academy of Architecture for Health (AAH), AIArchitect spoke with leading architects, administrators, and physicians about the evolving relationship between design and healthcare. As practice begins to reflect the new research, the blending of "outside" and "inside" space takes on corporeal dimension. Summary: New studies are linking the architecture of healthcare facilities to the quality of patient care, operational efficiency, and caregiver performance. In anticipation of the fall 2009 conference of the Academy of Architecture for Health (AAH), AIArchitect spoke with leading architects, administrators, and physicians about the evolving relationship between design and healthcare. As practice begins to reflect the new research, the blending of "outside" and "inside" space takes on corporeal dimension.

The new psychiatric facility in Worcester, Mass., designed by Architecture+ and Ellenzweig, will house 320 patients within a village-like setting. The facility is designed to be more intuitively navigable than typical large institutions. Landscape architecture by Horiuchi Solien Inc.

In the popular imagination, conventional hospital environments often fall short of therapeutic. Cold fluorescent lighting and low ceilings alone are enough to make some people feel ill. Although institutional budgets and stringent safety codes may hamper design innovation, architects and healthcare professionals are incrementally improving the environments of hospitals, clinics, and long-term care facilities.

A decade ago, the connection between patient safety and the healing environment was dubious at best, according to Francis M. Pitts, FAIA, founding partner of Architecture+ in Troy, N.Y. When Pitts moderated one of the first national conferences on therapeutic environments in 1995, he recalls: "The whole notion was greeted by many architects as though we were odd folks who had had too much granola." Since that time, patient-centered design has become a catchphrase, reflecting evidence that the hospital environment has an impact on patient safety and medical errors.

"A hospital is a high-tech environment, but it doesn't have to be scary," says Norman Rosenfeld, FAIA, a principal at Stonehill and Taylor Architects and Planners in New York City. Rosenfeld and his firm strive to imbue the patient experience with some of the comforts of hotels, of which they have designed many. This requires the architect to work with hospital administrators and nursing staff to establish a higher level of service. It also requires understanding the intricate details of daily operations—from laundry to communications to food service—to be able to persuade reluctant hospital officials to try something new, says Rosenfeld. Otherwise, "they just want the same thing as before, but bigger."

Fortunately, not all large institutions are resistant to change. Joseph Strauss, AIA, director of planning and design at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, leads a design standards group that meets regularly to review new research and practices in the field. "We are very interested in sustainability and LEED™ certification," says Strauss. The Cleveland Clinic has eliminated the use of vinyl flooring and sheet vinyl throughout its facilities and recently installed LED surgical lights to cut down on energy and cooling costs. What's more, "the LEDs provide much better light for the surgeons, because the 6-to-12 bulb fixtures create less shadowing."

Clearly defined natural light sources, distinctive forms, orienting views, and nodes of activity help compose the "natural wayfinding system" inspired by the work of Kevin Lynch and brain researchers at the psychiatric facility.

Healthcare architects are increasingly asked to ground their designs in research-based evidence, just as doctors base their diagnoses and prescriptions on scientific evidence. Research, of course, begets new questions. Does evidence-based design conflict with eco-effective design? Do images of nature help patients recover more quickly? How can high-tech healthcare environments be made more humane? These questions and many others will be discussed in depth at the upcoming AAH conference. Ron Smith, AIA, senior project manager at HOK Houston, will lead an open forum discussion, "Therapeutic Health Environments." Expert in current methodologies for measuring and evaluating the results of design, Smith sees these evidence-based techniques as part of the longer historical arc of architectural knowledge. "Evidence-based design is really just an extension of what we've always done as architects, basing our decisions on good sound judgment and experience," he says. "Every project is a laboratory to some extent." What's new is the use of research methods borrowed from social science—rigorous interviews, surveys, and ethnographies.

Not only the health of patients is at stake in clinical environments, but also the health of caregivers. According to Ron Smith: "Many nurses leave the workforce because of the very stressful and sometimes hazardous environment that they have to work in. There is a lot of value gained for the hospital itself and for the healthcare industry in general when we can create a better work environment." Bringing in natural daylight is widely believed to reduce stress levels, which in turn can reduce medical errors. Smith has also used carpet tiles to quiet busy areas. According to Frank Pitts, there is evidence that maintaining natural circadian rhythms can reduce nurses' risk of contracting cancer. But the need for so many private spaces in a hospital or clinic makes daylight harvesting a tricky endeavor, especially on a tight urban lot.

Healthcare and evidence-based design

Drawing upon the work of the urban planner Kevin Lynch and recent neuroscientific research about how the human brain navigates space, Pitts and Architecture+ have designed a new psychiatric facility in Worcester, Mass., with a more intuitive, "natural wayfinding system." The subject will always be in a position to see natural light, to understand the direction it's coming from, or to see an orienting form or view. The building plan is less like a Cartesian grid and more like a village or branching stream, with paths, edges, nodes, and landmarks following Lynch's notion of mental maps. "We believe the traditional wayfinding system of colors, letters, and numbers isn't a natural way for anyone to navigate anything, except maybe a chessboard," says Pitts.

The presence of art—although not necessarily what kind of art—arguably has a salutary effect on both patients and caregivers. The daily experiences of Dr. Rob Kahn, an outpatient clinician at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, seems to corroborate this theory. At the primary care clinic in which he works, the walls have paintings of large, tree-like forms incorporating children's books. "The art doesn't completely alleviate the fear of shots and blood draws, but it sets a different tone," says Kahn. "It also ties into reading and readiness for school." Art also figures prominently in the complete redesign of a Cincinnati clinic serving teens, where local youth artists from the Artworks program were commissioned to make the space more inviting. Dr. Jessica Kahn, a physician and former architecture student, and her colleagues spent a year designing their new clinic before the official architects got involved.

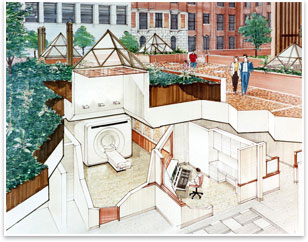

Stonehill Taylor Architects and Planners used 10 x 10 foot pyramidal skylights to bring soothing daylight into the below-ground MRI Procedure Rooms at Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York City. The skylights can be opened to allow replacement of large medical equipment.

Innovation for control and care

Large institutions operate millions of square feet, continually renovating and expanding their facilities to meet changing needs. This allows them to test and perfect new design ideas. Michael Browning, director of construction services at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, recounts how a seemingly minor detail can prove to be a very sensitive issue: the integral blinds on the glass doors of patient rooms. When glass doors were first installed, patients' families would often leave the blinds closed for privacy, forcing nurses to constantly knock to ask permission to open the blinds or enter the room for routine checks. This impeded effective care. So, in the next renovation, the hospital installed controls on both sides of the window.

Sometimes a technological breakthrough leads to new spatial challenges. Starting in the 1990s, the adoption of digital data networks allowed nurses to chart patient records from a computer at the patient's bedside. Today, they no longer need to shuttle back and forth to a central nursing station and therefore can disperse to smaller, localized stations serving 8-12 patients each. Although the decentralized system has improved patient monitoring and data processing, says Robert Kahn, the data entry terminals "can create a barrier between you and the family. The question is how do we enter electronic information and still face the family?" Michael Browning says the hospital is testing ways to make the computers less intrusive by modifying the location, mount, and style of the swivel arm for an upcoming 200-bed renovation.

A study published last year in the AAH Journal proposed a new patient room prototype that sought to address problems related to "inadequate lighting, absence of daylighting, noise, double occupancy rooms as opposed to single occupancy rooms, lack of standardized rooms, materials, and layout." The authors' attention to minute functional and sensory details reveals the complexity of creating genuinely therapeutic environments. In the wry words of Norman Rosenfeld: "Maybe a nuclear plant has greater complexity, but probably not." |