| Pushing the Limits: Contemporary Parisian Architecture in Historic Contexts How do you . . . blend historical and contemporary architecture in a historically centric city such as Paris? Summary: Paris is always on the forefront of fashion, and, believe it or not, this is also true of trends regarding new design in historic contexts. While the publicity garnered by IM Pei’s Louvre pyramid in the 1980s brought about a paradigm shift in the mass acceptance of Modern architecture as a complement to a well-known historic monument, eye-catching designs continue to make statements in historic contexts throughout Paris. The projects highlighted in this article mark current trends that choose either to contrast with or demure to their historic neighbors. It is important to note that, given French preservation laws, which require any construction within a 500-meter radius of a classified monument to be reviewed for impact to the historic resource, all of these projects were reviewed and approved by the Service Departmental D’Architecture and Patrimoine or SDAP (the preservation planning office) for the City of Paris during the design phases.

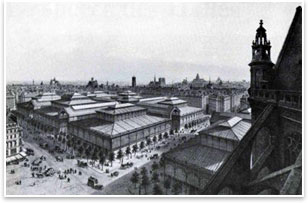

Cover of the competition results for the new Les Halles project. Competition for Les Halles One of the most high-profile new projects in Paris is the competition for Les Halles completed in the summer of 2007. Originally the city’s central market, the historic Halles, immediately north of the Pompidou Center and adjacent to the massive, Gothic St. Eustache church, were demolished in the mid-1970s and replaced with a modern shopping center (largely subterranean) and transportation hub. The new project aims to retain the same program while eliminating the suburban mall feel of the existing building. The winning entry by architect Patrick Berger, a “Canopy for the New Halles” proposes to cover the large area with a luminescent canopy and glass walls, hopefully permitting views across the site and a clear delineation of the void in the earth that contains the massive subway interchange and other program components.

Les Halles, Paris, circa 1900. Photo courtesy of the Commission du Vieux Paris. Historic views of the area are quite charming, and it can be assumed that such structures would be demolished today only after great protest and environmental analysis. Although the proposed canopy is clearly an improvement over the dated and oddly sited shopping mall, the winning design (unlike some of the other competition entries) provides no direct reference to the size, scale, massing, or texture of the historic market buildings. Is the proposed design contextual? Only in the respect that it reads more as a park, or void, in the urban fabric than an actual structure. Time will tell if this proposal is actually constructed and how it ages with the neighborhood around it.

New Ministry of Culture Building, Paris. Photo:Wendy Hillis, AIA. September 2007. The New Ministry of Culture Building Generated by a competition launched in 1995, this project brings together all of the dispersed services of the Ministry of Culture on an entire block not far from the Palais Royal (1st Arrondissement). The architect, Francis Soler, elected to retain both existing buildings on the site—an early 20th century commercial building with a classically inspired stone exterior and a Modern 1960s office building—and update them for a new function with a unifying façade. With minimal intervention, Soler was able to draw together this ill-matched pair in a metal net that wraps around the entire block and creates a uniform surface. This net screen veils rather than effaces the traces of the original buildings and also reveals them in a new scale on the block; one that equals the scale of its neighbors, such as the Louvre. While the treatment succeeds at blending the immediate disparities between the two buildings, its design unfortunately falls short at close range. The striking exterior filigree is rather flat and chunky when viewed up close, and the interiors of the renovated buildings are dull and uninspired.

New Ministry of Culture Building, Paris. Photo: Wendy Hillis, AIA September 2007. Le Fouquet Hotel on Avenue George V One block behind the famed Café Le Fouquet on the Champs Elysées, stands a building that clearly coveys its architect’s disdain for the jurisdictional requirements that attempt to steer new design into the realm of replication. Completed in 2006, the structure is clad in cast concrete, created with molds taken from adjacent 19th century buildings, in an attempt to appease those who promote slavish contextualism. As a result, the overall form is replicated, as are some of the texture and scale of the adjacent buildings, but that is where similarities end. The architect, Edouard Francois, willfully manipulates the edges of the structure (ending panels in mid-relief) as well as placement and style of the door and window openings to show that the exterior skin bears no relation to the interior structure or program of the building. While notable as a one-off statement (the building draws crowds of tourists who stop to gawk at its strange façades), one can’t help but believe this design solution for historic infill will quickly lose its novelty if replicated indiscriminately in other contexts.

Hôtel Le Fouquet Paris. Photo: Wendy Hillis, AIA. February 2008. Invisible Solutions

Hôtel Le Fouquet Paris.Detail of molded concrete panels. Photo: Wendy Hillis, AIA. February 2008. Similarly, a theme that is well on its way to being overused is the vegetal wall, which first gained widespread notoriety in Paris with the completion of Jean Nouvel’s Musée du Quai Branly, immediately adjacent to the Eiffel Tower. The Paris SDAP office has seen a marked increase in the number of projects that propose this solution. (I sat through five such presentations in my three-week internship with them in 2008.) These designs are promoted as “appropriate” because, like the glass option, the new buildings supposedly disappear into the landscape and don’t compete with the historic context.  In Paris, even construction scaffolding can make a statement. Photo: Wendy Hillis, AIA. February 2008. In Paris, as in most cities concerned with protecting historic urban fabric, the tactics used to design and then defend results of modern infill in historic contexts continue to be debated. Whether the proposed design is an attempt to create striking contrast or to minimize impact with near-invisibility, the appropriate solution is often determined as much by the breadth of the architect’s own design and public relations skills as it is the urban fabric within which it sits.

|

||

Copyright 2009 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› AIA Honors Six for Collaborative Achievement

› Doer’s Profile: Theodore H.M. Prudon, PhD, FAIA

This article is reprinted from Preservation Architect, the newsletter of the AIA Historic Resources Committee

Find out what the Historic Resources Committee is up to.

For questions or comments, contact Wendy Hillis, AIA.