| Knitting the City Back Together from Gray and Brown, with Green Reclaiming sites of forgotten industries for a new urban way of life How do you . . . take advantage of urban industrial infrastructure sites and turn them into parkland? Summary: After decades of civic hand-wringing over the fate of downtrodden and dysfunctional American cities, perhaps the most progressive sign of their resurgence is the increasing redevelopment of disused industrial infrastructure into urban parkland. Such projects honor and preserve the nation’s industrial history and create sustainable, vital green spaces that allow cities to develop in denser, more energy efficient ways. Do you know the Architect’s Knowledge Resource?

The AIA’s resource knowledge base can connect you to a podcast of landscape architect and author Julie Moir Messervy discussing her book, Outside the Not So Big House: Creating the Landscape of Home, which she co-authored with Sarah Susanka, FAIA. Visit the AIA’s government advocacy Rebuild and Renew site and the Navigating the Economy site. See what the Center for Communities by Design is up to. View the Slideshow Diller Scofidio + Renfro and Field Operations’ High Line park in Manhattan, which puts a landscaped pedestrian trail along an elevated rail line that weaves through skyscrapers and luxe condos, is merely the most headline-gobbling example of cities’ reinvestment in green. All across the nation, urban areas are taking abandoned rail lines, brownfield shipping corridors, and rotting piers and turning them into rehabilitated landscapes that illustrate the renewed, cross-generational desire of Americans for urban life. During cities’ post-industrial mid-to-late 20th century walk through the wilderness, these abandoned places fueled the fears of nervous suburbanites who had decamped via sprawling freeways to wide open subdivisions with their private lawns. Robbed of their industrial activity, these areas became perceived as places where bad things happened in the city—in docks, rail yards, and alleyways. High crime rates, poor education systems, and cheap suburban land created a Taxi Driver urbanism of blight and despair. Many of these problems still persist, but now the true costs of sprawling land consumption are too well known. And thus: “Cities time has come again,” says Ed McMahon, a senior resident fellow at the Urban Land Institute and the author of Green Infrastructure: Linking Landscapes and Communities. “If we are going to grow our cities and add density, we need to simultaneously green our cities. There are two things Americans have said they don’t like: They don’t like sprawl and they don’t like density. The way we overcome objections to density is with two things: high-quality design, and second, we’ve got to green our communities as we grow them.” Layers of history Like the High Line, Kiku Obata and Company’s elevated bike paths in St. Louis will eventually be counted among these rehabilitated rails. Called The Trestle, this 1.7 mile bike path travels along abandoned elevated train tracks that carried commuter trains full of people from Illinois across the Mississippi River into downtown St. Louis. The St. Louis-based firm’s project begins near a new small public park just north of downtown St. Louis, also designed by Obata. It then rises up the former commuter rail (which ceased running in 1958, according to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch) which Obata is updating with a myriad of sustainability and interpretive features. Its brown, hulking steel structure will have green-screened trellises grafted onto it to shade riders from the sun, which will also make the trail’s green rehabilitation visible to motorists passing by on adjacent roadways. Photovoltaic panels will power water pumps, and native plantings will grow where the trail is set back down at ground level. The Trestle will preserve the steel gate catenaries (used to hold the electric wires that powered its trains) on the trail, a warm reminder of St. Louis’s rich history as a shipping and transportation industrial hub.

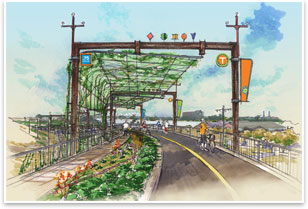

Kiku Obata and Company’s Trestle. Image courtesy of the architect. The trail will snake through active light and heavy industrial neighborhoods, as well as depressed and impoverished residential districts. Obata and her nonprofit developers (the Great Rivers Greenway District) want to build on the success of the city’s downtown redevelopment and the influx of 20- and 30-something homebuyers moving into the areas immediately north of downtown. Both designers and developers say The Trestle is an opportunity to rebrand this part of the city—to create a destination and admired amenity, so that north St. Louis can be re-integrated into the cities’ polite society of neighborhoods. From The Trestle, visitors will have a unique view of the city’s urban fabric that reveals its history. Beginning at the riverfront where the city began, through industrial districts, to a commercial corridor, to what was once the suburban fringe, the sweep of industrial America’s fortunes and faults are expressed and explained via interpretive exhibits along the way. “It’s an interesting experience to ride this 1.7 miles and see the changes in landscapes and context and different ecologies,” says Kiku Obata, Assoc. AIA. “We’re going to tell that story on The Trestle.” The Great Rivers Greenway District is funding the project through a sales tax levied on St. Louis and the surrounding counties, which generates $10-11 million per year. This income must be divided among all of the dozen or so Great Rivers Greenway’s recreation trail projects. The baseline budget for The Trestle is estimated at $12-15 million, but with all the amenities called for (such as public art installations and active sustainability features), this price could double, and they may be forced to move construction into phases, especially given today’s stricken design and construction industry. It is hoped that construction can begin in 2011, but it may take as long as five years to completion. Unfortunately, fundraising for The Trestle doesn’t have the media attention and dollar-grabbing celebrity sheen of its East Coast cousin, the High Line. “Unlike the High Line, we don’t have folks like Kevin Bacon living right next to it,” says Todd Antoine, deputy director for planning at Great Rivers Greenway.

W Architecture and Landscape Architecture’s West Harlem park. Image courtesy of Alison Cartright. Successful projects that can overcome the credit-starved design and construction industry will likely be hailed as exemplars of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act’s attention to the built environment. The AIA estimates that the economic stimulus package that became law in February contains $130 billion worth of funding for design and construction initiatives. Projects like The Trestle, with their emphasis on public and civic life, urbanism, and resourceful rehabilitation of forgotten assets, are tailor made for such a wholesale investment in the nation’s infrastructure. They also move the concept of infrastructure into new programmatic arenas. McMahon says he’s witnessed a shift in the perception of what constitutes “infrastructure.” No longer are green spaces to be considered pleasant “amenities.” They are just as essential as traditional infrastructure, like bridges, freeways, and sewer ducts. Just as the nation must repair and renovate its “gray infrastructure” so too must it invest in its “green infrastructure.” McMahon’s words are echoed by the AIA Rebuild and Renew government advocacy plan, which calls for architects to address the nation’s economic troubles with design solutions that make cities and towns more livable and sustainable. Coming full circle The firm of Barbara Wilks, FAIA, W Architecture and Landscape Architecture, has reconnected several cities’ waterfront industrial zones though park spaces. Her West Harlem waterfront park, completed in the fall of 2008, placed a landscaped pedestrian walkway and small boat launch in the Hudson River, just below an elevated freeway. The New York-based firm is also one of the shortlisted finalists in a design competition in Philadelphia to turn a one-acre finger pier on the Delaware River into a pocket park. (The High Line’s landscape architects Field Operations are also on the shortlist.) The Pier 11 park is budgeted at a modest $3.5 million and scheduled to open in 2010, according to the Philadelphia Inquirer. The first order of business for these projects, Wilks says, is to reestablish industrial zones as a place for people. “The harbor used to be a part of life,” she says. Even the tiny Pier 11 used to be a destination. It had market stalls where people could shop among the wares that came to the city on ships. As shipping industries grew and became more complex, security and other concerns meant that industrial waterfronts became scaleless and intimidating landscapes not for people, but for machines. Pedestrian scale and access all but disappeared. Massive cranes, flatbed-sized cargo boxes, and trucks—not people—ruled the waterfronts. The spread of the automobile encouraged the building of freeways, often on waterfronts at the edges of cities, further separating pedestrian public life from the water. “If you build your city around cars, you get more cars,” says McMahon. “If you build your city around people, you’ll get more people and better places.” When heavy industry began to leave inner cities in the latter half of the 20th century, these areas became completely desolate. Meanwhile, cities often failed to remember the potential real estate boost that park-side property encourages. (Think Central Park.) “People want to get back in contact with the water,” Wilks says. “In some ways it’s come full circle.”

Marta Fry Landscape Associates’ Mission Creek Park. Image courtesy of Marcia Liberman. Looking along the edges Mission Bay was once where ships would dock and unload cargo to be transported into the city and along the Bay via rail lines. Eventually, the Port of Oakland began to rival San Francisco as a shipping destination, and trucks became the primary way cargo got from ship to city. For a time until 1998, when this redevelopment began, the Mission Bay landscape was a checkerboard of abandoned lots and dilapidated warehouses. In a unique public-private partnership, the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency and master developer Catellus divided the land into separate parcels and have hired several landscape architecture firms to design parks that are in various stages of completion. The entire area’s build-out is expected to continue for another 15 years. Kelley Kahn, of the Redevelopment Agency, says these parklands are especially needed to make new mixed-use developments attractive and livable places. “You build a few housing projects and you get a few offices built, but it’s not till the parks go in that it really starts to feel like a neighborhood.” These parks, she says, create a destination for people from more established adjacent neighborhoods to visit, thus connecting new urban fabric with old. Mission Bay is on a peninsula located less than half a mile southeast of downtown San Francisco, separated from the rest of the city by Mission Creek. Marta Fry Landscape Associates designed some of the neighborhood’s first parks. Fry’s section of Mission Creek Park consists of a long waterfront esplanade along the northern bank of Mission Creek, a public plaza in the middle of it, and a sports park nestled under a freeway overpass. Fry says Mission Bay and Mission Creek Park are examples of the resourcefulness designers are going to have to demonstrate to build green spaces for cities. “We’re clearly looking at the edges,” she says. “We’re all scrambling for useable space, whether it’s for development or recreation.” She speaks of the urban “immediacy” afforded by these projects and the growing recognition that places to live, work, and play don’t have to be separated by long, car-bound commutes. The people coming to this realization are fueling a nationwide re-urbanization that reinforces the notion of cities as centers of cultural capital. A USA Today report recently revealed that growth rates in central cities are starting to outpace their suburban counterparts. As described by Richard Florida, author of Rise of the Creative Class, cities gain their economic strength from the creative professionals that live there—scientists, writers, educators, artists, entertainers, and, of course, architects. These professionals feed off interactions with other creative class members that can only come with dynamic and dense urban environments. If cities are the economic engine of the country, these people are the engineers. And they won’t compromise on having ample parks and green space. Opposites no longer “It’s the idea that nature and the city aren’t really separate,” says Wilks. “You have to think of nature as being part of the city. We’re not separate from nature. The city and nature are not opposites anymore.” And from a sustainability perspective, the city and nature cannot be opposites anymore. As these reclaimed industrial lands show, sustainable development is virtually defined by embracing the efficiencies of urban life along with the balance and equilibrium of nature. |

||

Copyright 2009 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||