Shovel-Ready Skills: Architects Are Integral to Infrastructure

A new set of challenges and opportunities await architects

By Sara Fernández-Cendón

Summary: The economic downturn has brought about a renewed interest in public works. As skilled problem-solvers, architects can contribute an insistence on wise use of resources, an understanding of human aspiration, and a sharp focus on community to the rebuilding effort. Architecture firms across the country are gearing up for the task.

Commercial and residential construction projects are among the many

casualties of the economic downturn. This is not news to architects

and engineers whose firms have seen declining activity for 11 consecutive

months as of January 2009, according to the AIA Architecture Billings

Index.

Enter the $787-billion economic stimulus bill known as American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, signed into law Feb. 17, 2009. The Obama Administration estimates the massive stimulus package provides $150 billion for new infrastructure projects, and announced this part of the bill as “the largest increase in funding of our nation’s roads, bridges, and mass transit systems since the creation of the national highway system in the 1950s.”

In response, the AIA has developed Rebuild and Renew, an aggressive legislative agenda for this year calling on Congress and the current administration to pursue policies that will stimulate work for architects and promote the profession’s involvement in the creation of a safe and efficient infrastructure for the 21st century.

Architecture firms are gearing up for the task. Although still unsure about how many infrastructure project opportunities might arise, many say they certainly hope to be involved. Based on their experience working on industrial projects in the past, architects who don’t specialize exclusively in this type of design and construction nonetheless agree on what the profession as a whole can contribute to the rebuilding effort.

Resourceful problem solving

Back in the mid-1990s, Polshek Partnership Architects was charged with the task of providing a space to house the printing facilities for the New York Times.

“Our client, David Thurm, realized the site was on a major

highway in New York City, a highly visible location,” says Richard Olcott, design partner with Polshek Partnership Architects. “He

took it as an opportunity to make something better than your average

box. He realized it would cost a bit more money, but he knew the

payoff would be considerable.”

Located along the Whitestone Expressway in Queens, N.Y., one of the 540,000-square-foot structure’s most notable features is the plain, yet striking view of the huge presses inside afforded by large glass areas on the building’s skin. Colors, bold graphics, and other simple and inexpensive elements were used to enhance the design and turn a utilitarian structure into an unmistakable icon.

Polshek Partnership, which has done a number of museums, educational facilities, and many other residential and commercial projects, approached this more utilitarian project the same way it does any other project. It provided an “affordable, lasting, and practical,” solution, as Olcott describes it, but it did so in a way that acknowledged the history and character of one of the city’s most revered institutions.

The firm is currently working on another industrial project—the Newtown Creek Water Pollution Control Plant, to be completed in 2013. The new plant, located within a residential neighborhood in Brooklyn, N.Y., will replace an outmoded waste water treatment facility. In Olcott’s words, the project is “too big, too visible and too important” not to use serious architecture.

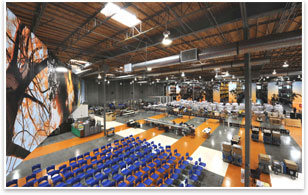

In designing a more modest project, Michael Lehrer, president of L.A.-based Lehrer Architects, used an approach similar to the one used by Polshek Partnership in the New York Times printing facility. The Los Angeles County–Registrar Recorder’s Operations Center, completed in 2006, is a 110,000-square-foot storage warehouse for records and voting materials. The facility is also where votes are counted and processed after elections. In designing a more modest project, Michael Lehrer, president of L.A.-based Lehrer Architects, used an approach similar to the one used by Polshek Partnership in the New York Times printing facility. The Los Angeles County–Registrar Recorder’s Operations Center, completed in 2006, is a 110,000-square-foot storage warehouse for records and voting materials. The facility is also where votes are counted and processed after elections.

In the final design, Lehrer used a number of inexpensive elements to add what he sees as immeasurable value. Occupied offices are located along the edges of the structure, where employees can enjoy daylight and views, while storage space is located deep inside the building. Color and large banners were also used to create a space that, in Lehrer’s words, “elevates the spirit”—and all of it was done for about $5.5 million.

“Economy as an architectural virtue means getting maximum value out of every dollar,” he says. “Our particular ability to make the best use of resources is absolutely vital in an economy like this.”

Elevating the task

Michael Lehrer understands the past decade as a period during which architecture became the medium of cultural meaning and conversation. He celebrates that role and casts the current transition precipitated by the economic downturn not as a break, but as an opportunity to expand the reach of good design.

“In the last 10 years design has been elevated, but this elevation happened in an environment of abundance and on a fairly refined level,” he says. “Now, in a time of radical limits, every single move counts to raise the bar. The architect’s gifts of enrichment and delight must happen at a more rudimentary existential level.”

No matter the size or nature of the project, Lehrer believes it is the role of the architect to define the problem at hand in ways that inspire solutions. About the Los Angeles elections center, he says the project didn’t start out with high aspirations.

“We tried to define and draw out the meaning in what was seen as an extremely utilitarian enterprise,” he says. “We, the architects, established that ‘this is the infrastructure of democracy.’”

As Lehrer sees it, this act of the architect is especially vital in infrastructure projects, which often require the resolution of a supposed conflict of purpose. It is the role of the architect to figure out what kind of delight might be possible in a water treatment facility, for example. Meanwhile, the kind of delight to be had in a museum is inherent to its mission as a cultural institution—no conflict there, says Lehrer.

When the task at hand is not designing a museum, but a highway overpass or a warehouse, the architect’s role is ever more vital.

“You can’t give short shrift to people’s aspirations, or their engagement and passion for the work they do, the places and cities they live in, and the streets they live on.”

Rich von Luhrte, president of Denver-based RNL, agrees. In addition to a variety of commercial, residential, and institutional projects all over the world, for years RNL has worked on industrial projects, many of them vehicle maintenance facilities, for cities across the U.S.

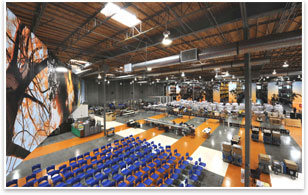

One of such facilities, the Elati Light Rail Maintenance Facility, was built as a space to clean, maintain, and inspect the light-rail fleet operated by Denver’s Regional Transportation District. While focused on the utilitarian purpose of the project, RNL did not ignore the needs of the employees who would use the facility. The design incorporated a number of human elements, such as the maintenance area’s translucent wall panels, which allow natural daylight to flow in, creating a pleasant work environment and reducing operating costs. One of such facilities, the Elati Light Rail Maintenance Facility, was built as a space to clean, maintain, and inspect the light-rail fleet operated by Denver’s Regional Transportation District. While focused on the utilitarian purpose of the project, RNL did not ignore the needs of the employees who would use the facility. The design incorporated a number of human elements, such as the maintenance area’s translucent wall panels, which allow natural daylight to flow in, creating a pleasant work environment and reducing operating costs.

“There is great value in function-driven architecture, in projects that support the most vital functions of our cities,” says von Luhrte. “If you understand that and celebrate it, you can maintain design quality and integrity. That doesn’t necessarily mean the building will be made out of shards of titanium; but it does mean the building will be a great piece of architecture that serves its purpose well and serves the community.”

Von Luhrte says about 15 percent of RNL’s work has been transportation-related for the past 10 years. Today, he estimates that number has risen to about 40 percent, and the company hopes to continue working on these kinds of projects.

“If you think of infrastructure building as community redevelopment, all of a sudden the task becomes something that architects can have a huge impact upon.”

Building Community

The Whitney Water Purification Facility and Park project involved a thriving 21st-century neighborhood in Hamden, Conn., and an obsolete 1920s industrial plant occupying 14 acres right in the middle of it.

“We proposed a landscape, rather than just a building, to make the site a publicly accessible park,” says Chris McVoy, senior partner with New York-based Steven Holl Architects and partner in charge of the project. “We added a public good, a public benefit to the project. What started out as a site closed off to the public became a common asset.”

The $46-million facility, completed in 2005, consists of water treatment facilities beneath a public park and a 360-foot-long stainless steel sliver that houses public and operational programs.

The new plant, which provides a water supply to south central Connecticut, incorporates a number of sustainable design elements, including a huge green roof featuring skylights to let natural light into the water purification plant below, and a renewable energy system to heat and cool the building.

McVoy emphasizes that the design of this facility fulfilled the practical purpose that led to its creation, but it also addressed the city’s need for green and public spaces. He sees this as a good model for cities considering investments in infrastructure.

“Infrastructure development requires serious capital,” he says. “Landscape might add up to 10 percent of the overall cost, but it provides a whole new dimension to the project.”

Richard F. Tomlinson II, partner with Chicago-based SOM, also believes infrastructure projects have the potential to change cities and build communities. “If they're done well,” he says, “they can be as memorable as a signature building.” Richard F. Tomlinson II, partner with Chicago-based SOM, also believes infrastructure projects have the potential to change cities and build communities. “If they're done well,” he says, “they can be as memorable as a signature building.”

He emphasizes how long it takes for infrastructure projects to gel. Often infrastructure finds itself catching up with the pace of commercial development, but Tomlinson highlights the importance of planning. "Infrastructure doesn't happen overnight, but we can provide the leadership and inspiration needed to get things moving," he says.

SOM has had a leadership role in the masterplanning of the Chicago Central Area Plan. The firm is constantly involved in this kind of work, and Tomlinson says it hopes to do even more in the future. Referring to the current economic situation, Tomlinson says periods of recession often become productive planning opportunities. This view is shared by many in the industry who are already looking beyond the current crisis and hoping that the end of the recession, whenever it comes, will give way to the implementation of well-considered plans for growth.

|

In designing a more modest project, Michael Lehrer, president of L.A.-based Lehrer Architects, used an approach similar to the one used by Polshek Partnership in the New York Times printing facility. The Los Angeles County–Registrar Recorder’s Operations Center, completed in 2006, is a 110,000-square-foot storage warehouse for records and voting materials. The facility is also where votes are counted and processed after elections.

In designing a more modest project, Michael Lehrer, president of L.A.-based Lehrer Architects, used an approach similar to the one used by Polshek Partnership in the New York Times printing facility. The Los Angeles County–Registrar Recorder’s Operations Center, completed in 2006, is a 110,000-square-foot storage warehouse for records and voting materials. The facility is also where votes are counted and processed after elections. One of such facilities, the Elati Light Rail Maintenance Facility, was built as a space to clean, maintain, and inspect the light-rail fleet operated by Denver’s Regional Transportation District. While focused on the utilitarian purpose of the project, RNL did not ignore the needs of the employees who would use the facility. The design incorporated a number of human elements, such as the maintenance area’s translucent wall panels, which allow natural daylight to flow in, creating a pleasant work environment and reducing operating costs.

One of such facilities, the Elati Light Rail Maintenance Facility, was built as a space to clean, maintain, and inspect the light-rail fleet operated by Denver’s Regional Transportation District. While focused on the utilitarian purpose of the project, RNL did not ignore the needs of the employees who would use the facility. The design incorporated a number of human elements, such as the maintenance area’s translucent wall panels, which allow natural daylight to flow in, creating a pleasant work environment and reducing operating costs. Richard F. Tomlinson II, partner with Chicago-based SOM, also believes infrastructure projects have the potential to change cities and build communities. “If they're done well,” he says, “they can be as memorable as a signature building.”

Richard F. Tomlinson II, partner with Chicago-based SOM, also believes infrastructure projects have the potential to change cities and build communities. “If they're done well,” he says, “they can be as memorable as a signature building.”